A view that appears to be gaining traction in some policy circles is that African countries need a benevolent dictator. The argument runs along the lines of suggesting that we’re not quite ready for democracy: Due to democracy’s apparent inability to produce economic growth, we should resort to a kind of autocracy that delivers material dividends. Some have framed this as a choice between inclusive or effective governance. But even this framing presents a false dichotomy. Effectiveness is a function of inclusiveness, though admittedly only if the condition of a relatively cohesive state is met.

These debates are not merely theoretical. For instance, empirical data from the Afrobarometer 2023 survey showed that 72% of South African respondents said they were willing to forego elections if it meant increased security and material well-being. This correlates closely with 63% of respondents to the same survey indicating that they did not feel close to any political party. From 2000 to 2015, respondents felt a strong sense of ‘partisanship’ (feeling represented by a party), but the post-2015 drop-off to 37% correlated with a sharp increase in those willing to forego elections. The drop in partisanship seemed to precipitate the willingness to abandon democracy. Until 2015, the trends largely moved together. Thereafter, they diverged radically. In other words, for as long as citizens felt represented, they were not willing to forego the right to vote.

There are all kinds of reasons for the steep drop in partisanship; state capture was exposed but prosecutions have been slow. Simultaneously, the institutional fabric required to attract investment that could generate labour-absorbing growth has been badly frayed. This is the very fabric required to ensure swift prosecutions. It also hasn’t helped that 2022 and 2023 were the worst load-shedding years since 2008. Voter turnout plummeted in line with the Afrobarometer survey results, and in the most recent elections was a poor 58%. So, do we need to drop all this idealistic democratic flag-waving and embrace aspirant autocrats who will set everything to right with an iron fist?

Many point to Rwanda as a model example. Not those who’ve fled for exercising judicial courage, but observers who see value in the empirical results and the clean streets. But let’s examine some empirical data from Rwanda against Kenya and Zambia, for instance, two (admittedly flawed) democracies in Africa that have withstood the test of power turnovers. One could choose any number of metrics, but there are at least three important determinants of whether a country possesses long-run success probability.

First is access to electricity for the rural population, as this indicates ability of the state to deliver public services outside of urban areas that can typically raise their own taxes. Widespread electricity provision is also a necessary condition for broad-based economic growth. As the graph below indicates, Kenya outstrips Rwanda by a country mile. By 2021, 68% of the Kenyan rural population had access to electricity, whereas Rwanda only reached 38%. Zambia had been beating Rwanda until 2013, after which it fell behind and is yet to catch up.

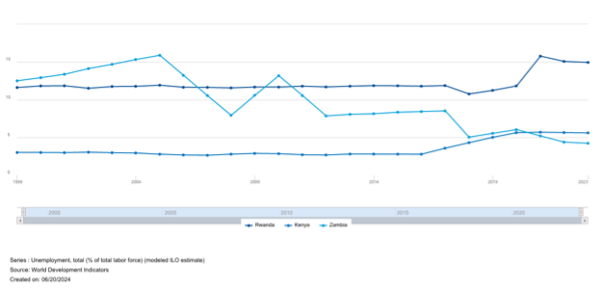

Second, Rwanda’s unemployment levels have climbed from a steady rate of 12% in 2017 to 15% in 2023. Kenya’s levels also rose during that time, but from 2.76% to 5.6%.

And Zambia’s rate, for all the country’s volatility and poor leadership until Hakainde Hichilema entered office in 2021, plummeted from a high of 16% in 2005 to beat even Kenya by 2023 with a low of 4.22%. An improved investment environment for mining will help to bring that figure even lower, provided the country can find a sustainable solution to its complex sovereign debt problem.

Thirdly, the “Country Policy and Institutional Assessment” (CPIA) “public sector management and institutions cluster average” scores (1=low and 6=high) of each country reveal that this is the only arena in which Rwanda wins. And it is indeed significant. The cluster “includes property rights and rule-based governance, quality of budgetary and financial management, efficiency of revenue mobilisation, quality of public administration, and transparency, accountability and corruption in the public sector.” This variable is more important for us to understand than ‘outcome’ data, such as economic growth, given how pivotal a country’s institutional framework is for catalysing and sustaining growth and poverty reduction in the long run. Success or failure is very often a function of institutional quality.

As the graph indicates, Rwanda’s score has climbed from 3.3 since 2005 and stabilised (or, in the alternative interpretation, stagnated) at 3.8 by 2022. Kenya started in the same place but had only increased to 3.5 by 2022. Zambia, by contrast, has declined from 3.2 in 2005 to 2.9 in 2022. The hope is that under Hichilema’s leadership, the country will implement the right institutional changes and reverse the decline.

By the above, one can understand why the Rwanda model seems attractive. However, when one considers the long-term risks, it is harder to understand. Kagame is a ruthless operator, and civil liberties are deeply repressed in Rwanda. Aspirant autocrats – especially when they become entrenched dictators – start to make mistakes that hurt the citizens who were perhaps willing to forego liberties such as a free press, an independent judiciary and a credible vote. “Big men” surround themselves with yes-men and avoid any checks and balances. Accountability goes out the window. Even patronage beneficiaries start to live in fear.

So, what to do then, given that democracy appears not always to deliver? An underappreciated 2006 paper by Michael Ross, “Is Democracy Good for the Poor?”, is worth consulting: “Over three decades [1970-2000, in which there was a radical reduction in child mortality rates across the world], there was also a dramatic rise in the prevalence of democracy; yet we find little evidence that the rise of democracy contributed to the fall in infant and child mortality rates. Democracy unquestionably produces noneconomic benefits for people in poverty, endowing them with political rights and liberties. But for those in the bottom [income] quintiles, these political rights produced few, if any, improvements in their material well-being. This troubling finding contradicts the claims made by a generation of scholars.” Indeed, this is a solid foundation for an argument that suggests that democracy might not always deliver for the poor and that democracy cannot be eaten.

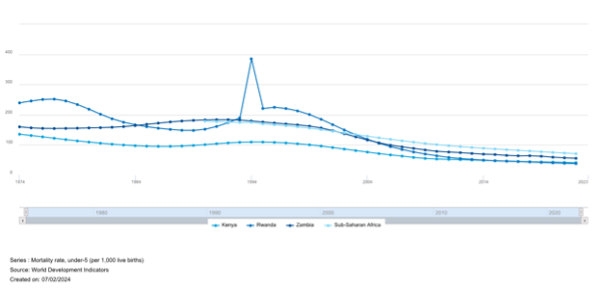

As the above graph shows, and to Michael Ross’s point, under-5 mortality has plummeted in Rwanda from 239.6 deaths per 1,000 live births (fifty years ago) to 38 by 2022. Zambia also made significant gains, as did Kenya. When one surveys the under-5 mortality data more broadly, on average, sub–Saharan Africa does worse than all three countries we’ve selected, coming in at 70.7 per 1,000 live births by 2022. Either way, the progress is significant across different political configurations. There are at least three important things to consider here.

First, a country’s political system may not have as strong a bearing on a variable like under-5 mortality as it does on long-run economic growth. Angola’s under-5 mortality plummeted after the end of the civil war there in 2002, even while inequality exploded, and poverty levels did not change significantly despite a huge influx of oil money. One explanation is that exogenous health interventions, often through foreign aid, can deliver a positive impact despite (and largely independent of) the political configuration. While it’s laudable that under-5 mortality is generally declining, this doesn’t necessarily tell us much about the employment prospects for those who do survive beyond five years of age.

At this point, sceptics often appeal to China’s success in lifting people out of poverty. As Yasheng Huang rightly points out, however, China could have done far better had it not reacted like it did to student protests in 1989 (the Tiananmen Massacre). That political crackdown also ushered in a period of reversion to economic ‘command-and-control’, where the forces of ‘capitalism’ were heavily directed by the state towards urban and manufacturing growth. The ‘directional liberalism’ of the 1980s, which Huang credits for China’s post-Mao (1978) success, was reversed. In a newly released book, Huang further shows how the Chinese Communist Party under Xi Jinping is at risk of elevating thought conformity over new ideas, which will lead to technological decline.

This trajectory was also predicted by Acemoglu and Robinson in their 2012 book Why Nations Fail, which entails a fascinating comparative discussion on the likely future trajectories of China and India. This is not to say that there are no lessons to learn from China’s remarkable rise, but it is not an easily importable model and carries significant risks. The key lesson is that institutional formation that suppresses citizen’s voices may temporarily result in economic progress, but it is not clear that such progress will reach a broad swathe of citizens or lock in long-term broad-based development.

Second, democracies themselves are highly heterogeneous and may, therefore, deliver a mixed bag of economic results. The Economist Intelligence Unit, for instance, presents four different types of political configurations. According to its 2022 report on global democratic health, only 24 countries—8% of the world’s population – lived in “full democracies.” A further 48 countries constituted “flawed democracies”, while 36 were “hybrid regimes”. The rest—59—were classified as “authoritarian regimes”.

Most African countries are classified as either hybrid (14) or authoritarian (23), with a few pockets of “flawed democracy” (6) here and there. Even Zambia and Kenya, which we examined above, are classified as “hybrid”, despite progress towards democracy. A hybrid regime is one in which “elections have substantial irregularities that often prevent them from being both free and fair.” They are also characterised by poor government effectiveness, weak rule of law (with a compromised judiciary) and widespread corruption.

As we’ll see later, democratisation—the process of deepening democracy—has positive long-run economic effects (on average), but the relationship is neither guaranteed nor linear. Convincing work in political science has shown that democracies struggle to consolidate when they enter electoral competition at low rates of per capita income and weak education outcomes. This is partly because sustaining and strengthening democracy requires a well-informed citizenry. Absent this, ostensibly democratic institutions can simply be used to advance authoritarian ends.

In an age of disinformation propagation that undermines electoral integrity and polarises people, having a well-informed citizenry could not be more important to guard against autocratic creep. Technological advances have certainly not been an unmitigated benefit for democracies, and many experts opine that the concentration of technological power in the hands of a few multinational firms may spell death for democracy unless we can find new models. This will ultimately concentrate wealth in the hands of the few at the expense of global broad-based development.

Third, external imposition does not work. Therefore, if democracy is simply imposed, we can expect that it will not deliver economic dividends. A major contention, often heard in places like South Africa, is that liberal democracy is incongruent with the informal norms underpinning how society functions. Indeed, there is plenty of good literature in the political economy sphere that shows that any models imposed from the top down that are incentive-incompatible with the distribution of power will likely fail. Understanding informal norms is, therefore, the key to designing political configurations that will work.

In South Africa, though, I do not share the view that the constitution was a unilateral imposition that means little to most citizens. It remains a critical document that has spared us the worst excesses of corruption and institutionalised constraints against the worst abuses of executive power. Moreover, while many citizens are subject to the relatively authoritarian rule of traditional chiefs and headmen, this does not mean that they are necessarily amenable to accepting a strongman as president so long as such a person delivers economic wellbeing. In South Africa anyway, this is a complex story because of how so many chiefs were co-opted under Apartheid to execute the programme of separate development.

The Apartheid government actively subverted informal norms to advance authoritarian ends. And the ruling party from 1994 to 2024 was not beyond utilising the same norms to deliver the rural vote. I would go further and argue that the failure to give legal expression to section 25 of the constitution (to provide security of tenure to citizens living in the former ‘homelands’) has been a major cause of South Africa’s inability to thrive economically, but that is a column for another time. What one does have to accept in this debate, however, is that some informal norms in South Africa potentially run against the grain of the kind of democracy envisaged in the constitution.

In summary, the clearest reason for why democracy appears to have failed in delivering economic dividends for African citizens is not that democracy is flawed per se, but that it hasn’t been sufficiently tried. To deliver economic results, democracy must first deliver government effectiveness—a capable state constrained by an active, informed citizenry and strong institutions. The final counter to the idea that a Rwanda model might be more fit for purpose in sub-Saharan Africa is found in a 2019 paper by a group of world-class economists (Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson among them). They ran several complex econometric regression models to try and isolate the impact of democratisation on economic growth. They found that “democratisations increase GDP per capita about 20% in the long run.” This is mostly likely due to democracies (on average) “enacting economic reforms, improving fiscal capacity and the provision of schooling and healthcare, and perhaps also by inducing greater investment and lower social unrest.”

Clearly, as Michael Ross points out, under-5 mortality (a sensitive indicator of poverty) has not necessarily reduced due to democracy being better than autocracy at reducing child mortality per se. Nonetheless, the results from Acemoglu and his co-authors show that the economic benefits of democratisation are not heterogeneous at different income levels. In other words, countries with more inequality and lower average income levels did not fare worse than their richer or more equal counterparts in terms of long-run growth.

The idea that democracy is bad for growth at early stages of economic development has therefore been debunked in the academic literature, though more clearly needs to be done to strengthen democracy to the point where it clearly delivers to citizens. Dictators can do great damage, as Kagame continues to do both at home and in places like the DRC, even while having made some incremental gains on the World Bank’s CPIA score. Civil liberties (enshrined, for instance, in South Africa’s constitution), to the contrary, can equip citizens to call for accountability, which still seems the most likely channel to achieve pro-poor growth.

This article first appeared in Business Live.

Dr Ross Harvey is a natural resource economist and policy analyst, and he has been dealing with governance issues in various forms across this sector since 2007. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town, and his thesis research focused on the political economy of oil and institutional development in Angola and Nigeria. While completing his PhD, Ross worked as a senior researcher on extractive industries and wildlife governance at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), and in May 2019 became an independent conservation consultant. Ross’s task at GGA is to establish a non-renewable natural resources project (extractive industries) to ensure that the industry becomes genuinely sustainable and contributes to Africa achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ross was appointed Director of Research and Programmes at GGA in May 2020.