The 2024 national and provincial South African elections will likely prove the most important elections since the seminal 1994 elections.

The country faces mounting socio-economic challenges including high unemployment, an energy crisis, water scarcity, high crime levels, and widespread corruption. Given these mounting challenges, can political parties respond adequately?

Leaders of various political parties at the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) Results Centre on May 9, 2019 in Pretoria, South Africa. Photo: Phill Magakoe/AFP)

More importantly, how do South Africans resonate with political parties, and what insight can these sentiments provide in understanding voter behaviour ahead of next year’s elections?

One response to these challenges is an increase in opposition parties contesting the elections. However, this increase has been accompanied by decreasing partisanship and voter turnout. What accounts for this discrepancy?

The answer is quite simple — South Africans are not oblivious to political parties’ short-sighted politicking.

While political parties appear to be more fixated on who is next in line to rule, South Africans are more concerned about who has the capacity to govern the country. Lower partisanship and reduced voter turnout indicate that the electorate has not yet identified a viable alternative to the ANC.

Voter turnout trends

Since transitioning into a democracy in 1994, South Africa has had six national elections. Over the years there has been a steady decline in voter turnout and levels of partisanship, which indicates a shift in voter behaviour.

Elections can be seen as the bridge between citizens and politicians. In this case, a continuous decline in voter turnout also suggests that there is a growing disconnect between citizens and politicians.

In turn, the shrinking partisanship manifests itself in lower voter turnout, spoiled votes, vote splitting, and reduced votes for dominant parties. Citizens who choose not to vote are generally dissatisfied with the political party that they had previously voted for. In this case, one would expect dissatisfied voters to alternatively vote for opposition parties.

But this is often not the case in South Africa.

Over 200 political parties are expected to contest in the 2024 elections. This is well above the 48 political parties that contested in the 2019 elections and the 29 that contested in the 2014 elections. Of these political parties, the three largest are the ANC, the Democratic Alliance (DA) and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF).

Since 2004, there has been a steady decline in voter turnout. In 2004, the Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC) recorded a voter turnout of 77%. In 2009, this modestly increased to 77.3% but dropped to 66.05% in 2019. In 2019, the ANC obtained 57.5%, the DA 20.77% and the EFF 10.8%. For the ANC, this is a decline from 62.15% in 2014 and 65.90% in 2009.

Although there is growing public discontent towards the ANC, opposition parties should not equate this to South Africans identifying them as viable alternatives. As political parties prepare for the elections, their biggest challenge will be winning the minds of dissatisfied voters. As such, political parties need to be seen as credible alternatives.

A general decline in voter turnout is suggestive of voter fatigue among South Africans, indicating that the current political landscape falls short of cultivating confidence. This prompts questions about the reasons for these declines and the impact that these declines will have on electoral behaviour.

One reason is South Africa’s electoral framework, which contributes to the weak link between the citizen and the elected representative. The national and provincial electoral framework of proportional representation through party lists does not allow citizens to directly elect officials.

The electoral system seems to generate a lack of accountability and responsiveness.

Eroding partisanship

The gap between voter turnout and increased opposition parties suggests that the average voting-age South African does not resonate with political parties. This implies that political parties are out of touch with their voter base.

There are approximately 14 million unregistered young South African voters between the ages of 18 and 39. Out of the 26,152,855 registered voters reported in October 2023, only 249 085 fall in the 18–19 age category, 3,731,060 fall in the 20–29 age category, and 6,625,551 fall in the 30–39 age category.

Similarly, the 2023 Afrobarometer round 9 survey indicates that 63% of South Africans do not feel close to any political party. This is a 10 percentage point increase from the 2018 survey. In the 2018 survey, non-partisanship was the highest in the 18–25 age category (29%) and the 26–35 age category (30%).

The latest survey indicates that out of the 37% that felt close to a political party, 52% felt close to the ANC, 17% felt close to the DA, 12% felt close to the EFF, and 7% felt close to the IFP. In the 2018 survey round, 29% of South Africans felt close to the ANC, 6% felt close to the EFF, 4% felt close to the DA and 1% felt close to the IFP.

In the same year, half of the partisans who intended to vote for the EFF or DA did not feel close to either political party.

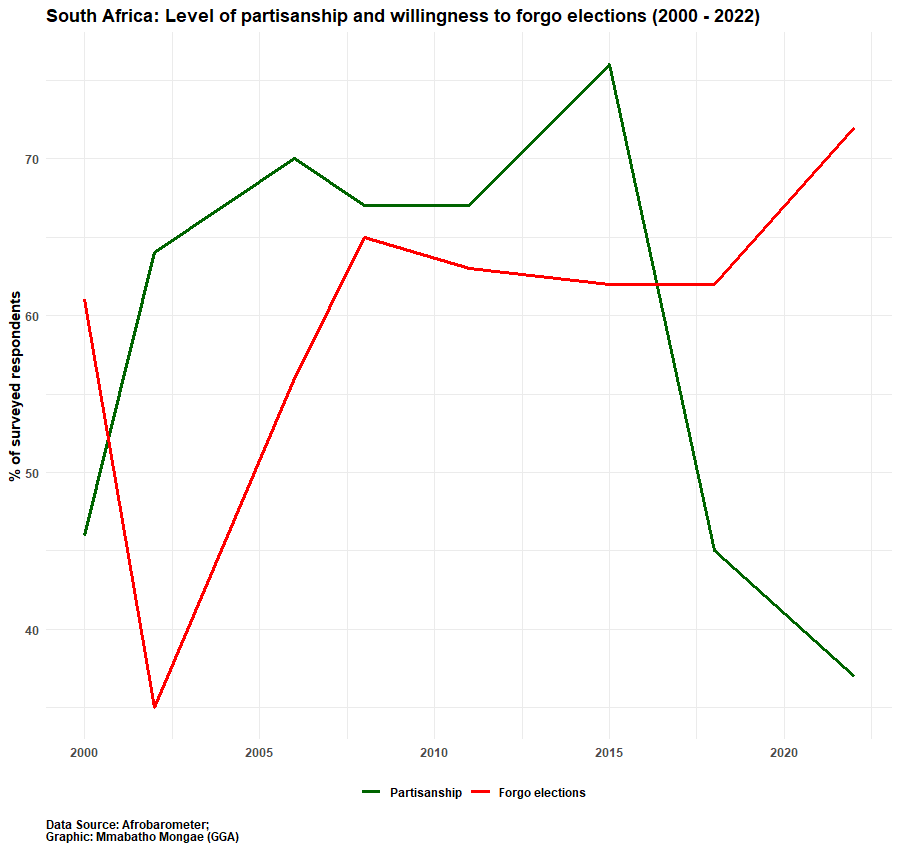

Decline in partisanship, voter turnout, and willingness to forgo elections.

When we juxtapose partisanship with voter turnout trends, we see that the two are simultaneously declining. Worryingly, 72% of South Africans are willing to forgo elections in favour of security, jobs and houses. These findings reaffirm the idea that the political terrain is no longer inspiring confidence in the average South African.

The plot provided depicts changes in levels of partisanship and the willingness to forgo elections. The plot illustrates that between 2000 and 2006 the percentage of citizens who felt close to a particular party increased from 46% to 70%.

During the same period, the willingness to forgo elections decreased from 61% to 56%. The figure also illustrates that between 2015 and 2022, there was a sharp decrease in the level of closeness to a particular party.

During this period, levels of partisanship decreased from 76% to 37%. Additionally, the willingness to forgo elections increased from 62% to 72%.

Linking voter turnout and partisanship

Based on these trends, we can observe that an increase in political parties is accompanied by a decrease in voter turnout and levels of partisanship. This calls for political parties to rethink how they engage with citizens. Moreover, this is also indicative of an ideological shift in politics. A shift that politicians, civil society, and citizens are trying to understand and characterise.

The growing gap between opposition parties, voter turnout, willingness to forgo elections and partisanship does not appear to be the result of voter apathy or South Africans giving up on South Africa. But it seems largely to be the result of the inability of political parties to formulate and communicate long-term, visionary, and creative plans and responses to the present and future state of South Africa.

This inability, or at best, limited ability, is a factor that ordinary South Africans are cognisant of. Hence political parties and more specifically opposition parties are struggling to find resonance with South Africans. For the average South African, campaigning for the removal of the ANC as the solution to the nation’s challenges lacks depth and vision.

Political parties need to shift away from superficial politics and rhetoric. Additionally, to appeal to the population at large political parties should steer away from being driven by merely obtaining seats, but rather by engaging more on how they plan to govern the country.

- A version of this article also appears in the Mail and Guardian week of 16 October https://mg.co.za/thoughtleader/2023-10-17-how-will-south-africans-vote-in-2024/

MmabathoMongaeis a Data Analyst within the Governance Insights & AnalystProgramme. She is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the University of the Witwatersrand, and her thesis research focuses on how governance quality influences popular support for and satisfaction with democracy in Africa. While completing her PhD, Mmabatho worked as Sessional lecturer in the International Relations Department at the University of the Witwatersrand and as a research fellow at the Centre for Africa-China Studies (CACS) at the University of Johannesburg. Her research interests include democracy, governance, Africa’s political economy, and quantitative social analysis. Mmabatho has published research for Routledge, EISA, and The Thinker.