More people in Africa live without electricity than anywhere else and there is little hope things will change soon

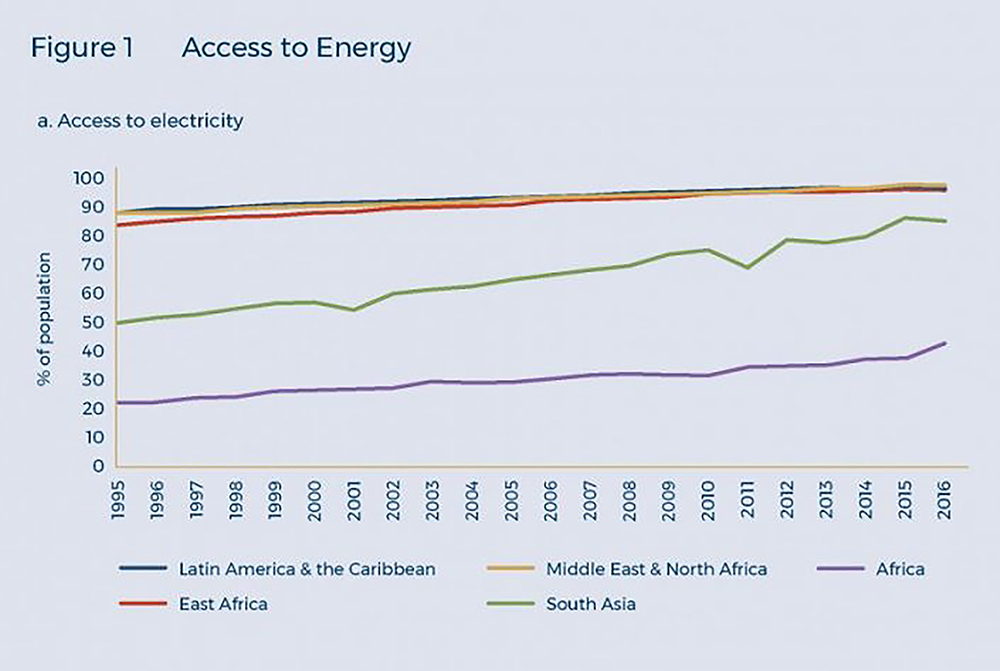

When it comes to access to energy, Africa’s figures are noticeably unimpressive. Nearly 75% of the world’s 789 million people who lack electricity live in Africa, according to an October 2020 International Energy Agency (IEA) report, and of the 2.6 billion people who lack access to clean cooking, 900 million are in Africa. While the rate of rural electrification in other parts of the world is above 70%, in sub-Saharan Africa it is just above 20%.

However, there has been progress. According to the IEA, the number of people on the continent without access to electricity, which stood at 610 million in 2013, fell to about 580 million in 2019. That gain, however, has been overshadowed by Africa’s ballooning population, and many remain without access to power. “In the past decades, access to electricity in Africa failed to level up with its booming population and this negates the drive for development milestones,” said Ubong Edet, director at Open Policy, a development-focused civic group in Abuja, Nigeria

Attempts by most African nations to significantly increase their citizens’ access to electricity over the years largely failed, hampered by policy missteps, poor funding, corruption and sometimes instability. The result is a dysfunctional power sector that has been unable to support economic activities that can create jobs, and education and healthcare services. Only an estimated 28% of health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa have access to reliable electricity, according to Powering Healthcare, a United Nations initiative.

The IEA says unless there is considerable improvement in investment and policies, Africa is certain to default on the global sustainable development goal of 2030 (SDG7), which seeks to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all. The current policy trajectories will see 530 million Africans still without electricity in the next decade, it says.

A woman disconnects her electricity counter in a bid to save money inside the courtyard of a workers quarter in Dakar, Senegal. Photo: AFP/Georges Gobet

“Despite progress in several countries, current and planned efforts to provide access to modern energy services barely outpace population growth,” the agency says.

It is an irony for a continent that is the most endowed with raw energy hydro, solar, oil, gas, coal and geothermal resources. Despite having more solar resources than any other region, Africa has only five gigawatts of solar photovoltaics – less than 1% of installed global capacity, says the IEA.

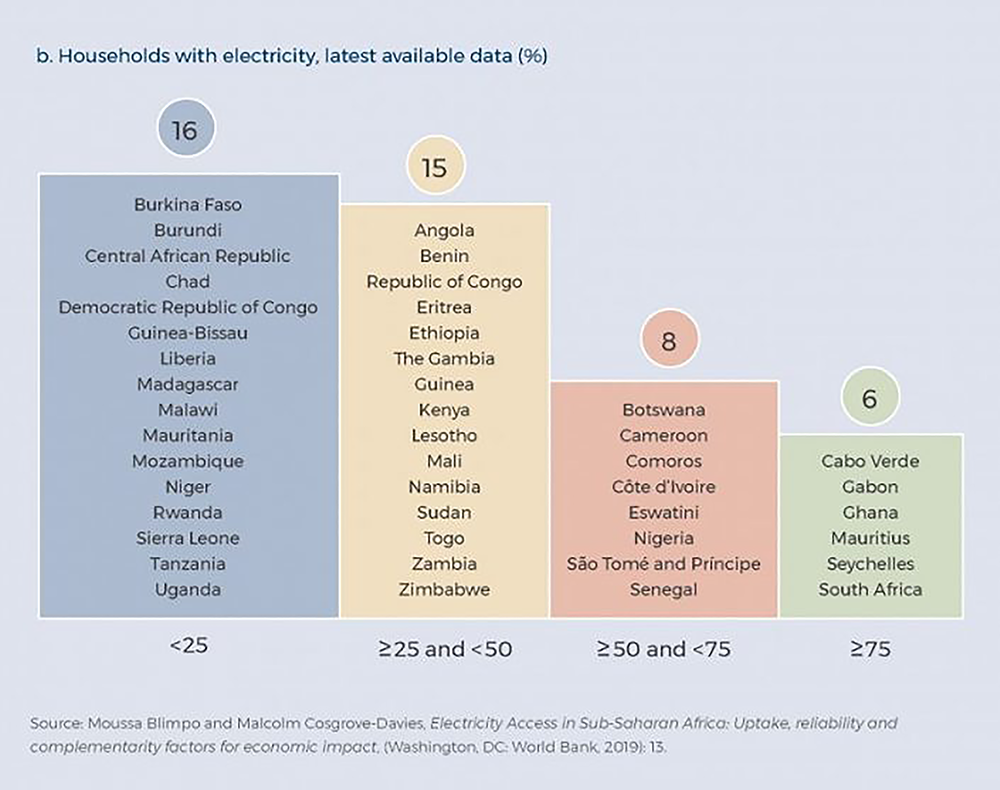

The bulk of the region’s energy deficiency is in sub-Saharan Africa, with Nigeria, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Uganda and Tanzania accounting for the largest number of people without electricity.

Years of efforts by African governments have failed to produce sufficient energy the continent needs for several reasons. The first is the funding gap.

The IEA estimates that sub-Saharan Africa needs $35 billion a year to ensure electricity access for all by 2030, and only a few countries have been able to mobilise enough funds locally for their energy projects.

Ethiopia, for example, recently raised 8 billion birr out of an expected 12 billion birr (about $550 million) for its Grand Renaissance hydroelectric dam through domestic and diaspora bonds.

Corruption is another factor. The anti-corruption group, Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project, said Nigeria has spent over $30 billion in the past two decades but has only managed to generate less than 7,000 megawatts of electricity, far less than required by its more than 200 million citizens. It said successive administrations had “squandered” huge amounts without a commensurate result.

There is also a policy challenge. Since jumping on the electrification trend in the post-independence days, poor management and a lack of political will have seen many African countries end up with unrealistic (or failed) mega energy projects. In contrast, Asia has, through the same period, had accelerated its electrification and achieved the most significant decline in the number of people without electricity worldwide between 2010 and 2018.

Source: World Bank

Africa’s modest improvement has been in East Africa. Here, Kenya, Ethiopia and Tanzania account for more than half of those gaining access to electricity, according to the Brussels-based Alliance for Rural Electrification. In Kenya, the electricity access rate rose triple fold within five years to 75% in 2018 as the country complemented grid connections with solar and geothermal systems.

Even with such progress, as of July 2020, only one country in Africa – Gabon – was “on track” to achieve SDG7, according to an analysis by the Sustainable Development Goals Center for Africa and the Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Twenty-two countries were “moderately increasing”, 28 were stagnating while three countries were “decreasing”.

African countries appear better on track to attain the more drawn out African Union’s own goal that seeks to harness, by 2063, all “African energy resources to ensure modern, efficient, reliable, cost-effective, renewable and environmentally friendly energy to all African households, businesses, industries and institutions.”

“Africa will have to raise its funding and actionable plans if it will ever meet up with the rest of the world developmentally in the coming years,” said Edet of Open Policy.

Access to electricity in Africa is also hampered by affordability and reliability. The unit cost of electricity to consumers in many African countries is more than double the cost in developed nations such as the United States, according to a joint assessment by Agence française de développement and the World Bank.

Also, even in instances where power is available, households spend hours without power. In 25 of the 29 countries in Africa examined by a World Bank report, fewer than one-third of firms had reliable access to electricity. Things worked relatively better in Liberia, Namibia, and South Sudan than in Nigeria, Kenya, Mali, and Tanzania, the report said.

Solving Africa’s energy problem requires proper funding and policy adjustment. Experts say off-grid renewable projects, like solar, should be Africa’s energy future because they are less costly and do not require expensive connections to the national grid, especially since the majority of the population live in rural areas.

A technician with electricity distribution company stands on ladder and repairs a faulty line in Lagos, on September 29, 2020. – The Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) has suspended the hike in electricity tariff for two weeks in line with agreement reached with the organised labour on the suspension of strike over the hike in electricity tariff and increase in pump price of petrol. (Photo by PIUS UTOMI EKPEI / AFP)

First, African countries will have to quadruple their rate of investment in their power sectors for the next two decades to bring reliable electricity to all Africans, the IEA said. The agency recommends an annual investment of around $120 billion yearly to bring electricity to all in Africa.

“We’re talking about 2.5% of GDP that should go into the power sector,” Laura Cozzi, the IEA’s Chief Energy Modeller, said in November 2019. “India’s done it over the past 20 years. China has done it. So, it’s something that is doable.”

Given the cost, the agency recommends using more mini-grids and says attention should be focused more on the huge potential that solar, wind, hydropower, and natural gas offer.

Source: World Bank

Despite evidence that solar and wind could provide cheaper and more environmentally friendly options to expand electricity in Africa, a number of African nations are shifting to nuclear energy.

They cite the threat of drought to hydropower and argue that nuclear power can provide a reliable support for renewables such as solar and wind.

In addition to South Africa, which has Africa’s only nuclear power plant, Ghana, Morocco, Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, Niger, Tunisia, Algeria, Zambia, Uganda and Sudan have considered adopting nuclear energy, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Norbert Edomah, an energy expert and senior lecturer at the Pan-Atlantic University, Lagos, says countries should adopt options that work best for them and should consider “contextual energy geography”.

“What works in East Africa may not work in West Africa,” he told Africa in Fact. Edomah advised policymakers to pay attention to “providing energy for productivity”.

“The question to ask is, what do people use energy for? In what way can we provide energy to improve livelihoods? Things that focus on livelihoods and improve productivity is what we should focus on,” he said.

There is an immediate constraint. The IEA fears the COVID-19 pandemic may reverse years of progress made in expanding access to electricity. It says that as governments attend to the immediate public health and economic crisis, utilities are bound to face serious financial strain. Also, increased poverty levels worldwide in 2020 may make basic electricity services unaffordable.

But Damilola Ogunbiyi, CEO and Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL) and co-chair of UN-Energy, said the pandemic also provided an opportunity that could be harnessed.

In a statement to launch SEforAll’s Recover Better with Sustainable Energy Guide for African Countries in June 2020 Ogunbiyi said, “COVID-19 has changed the world as we know it. As countries rebuild economies impacted by the pandemic, they are faced with a unique, once in a generation opportunity to ‘recover better’ with sustainable energy.

“There has never been a better time to invest in clean, efficient renewable energy. Countries that recover better with sustainable energy will see the pay off in the form of resilient economies, new jobs, and faster energy development. By making this investment, African countries can develop a competitive advantage.”

Ini Ekott is the deputy managing editor at Premium Times, Nigeria. He has researched and written extensively on governance and leadership in Africa. He is a former Wole Soyinka investigative reporter of the year, and was a member of the global team of journalists that conducted the Pulitzer-winning Panama Papers reporting

I work in Informal settlements in Namibia and this people can only do with Renewal electricity meaning Solar power I want to work on this.How can you help me.or how can I be part of this program.

Hi Katrina,

Thanks for getting in touch. Kindly contact Dutch-based NGO called Hivos (southern-africa.hivos.org) – one of their areas of focus is renewable energy and here are the contact details for their Southern Africa offices.

Southern Africa

20 Phillips Avenue Belgravia

P.O. Box 2227 Harare, Zimbabwe

T: + 263 (2)4 2250463 | (2)4 2706125

T: + 263 (2)4 2706704

F: + 263 (2)4 2791 981

E: sa-hub@hivos.org

Local Office South Africa

Postnet Suite 515, Private Bag X113

MELVILLE 2109, Johannesburg, South Africa

T: +27 11 7261090

F: + 27 11 726 5576

E: info@hivos.co.za