South Africa is presented with opportunities and problems created by the Trump-Musk regime

The USA is a preponderant power—it essentially dominates almost every aspect of international affairs. It is also South Africa’s second-biggest trading partner; this trade relationship is critical for funding the country’s fiscal deficits and deteriorating debt-to-GDP ratio. In 2022, exports to the US (7% of the total) were valued at nearly US$11 billion, while exports to China were valued at nearly US$23 billion (about 16% of the total).

To understand present SA-US relations, note that post-1994, the USA and SA entered into several multi-faceted strategic partnerships; these partnerships spanned security, energy, health, military aid, etc. Foreign aid and development assistance from the US to South Africa is valued at over US$500 million annually, more than half of South Africa’s total annual aid receipts.

Both the US and South Africa are important role players in Africa, and in the age of austerity, the United States needs partners. Moreover, for its grand strategy to be effective, the US needs to be able to effectively shape its security and foreign policy, and it needs key partnerships to do so.

Everett Kelley, president of the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) union, speaks during a ‘Save the Civil Service’ rally outside the US capital on 11 February 2025 in Washington, DC. Unionised federal workers and members of Congress denounced President Trump and his allies, including Elon Musk, head of the so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), for purging federal prosecutors, forcing out civil servants with dubious buyouts, and attempting to shutter USAID, all while branding government employees the “enemy of the people”. Photo by Kent Nishimura/GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA/Getty Images via AFP)

South Africa and Nigeria have been key in shaping Africa’s institutional architecture, including NEPAD, the AU, and the Pan-African Parliament. It has also led regional cooperation efforts, particularly in transforming SADC. The US has long relied on South Africa’s support for defence initiatives, given its leadership in the region. Over the years, South Africa has contributed significant funding, military resources, and political support to missions in the DRC, Burundi, Mozambique, and Sudan.

Cutting future funding to South Africa would have both immediate and long-term economic consequences for South Africa and [regional] political implications for the US. A major point of contention remains South Africa’s non-alignment stance—a policy established by Nelson Mandela and upheld by successive administrations, though inconsistently applied.

This tension reflects the intersection of politics and economics. The US is SA’s second-largest trading partner and fourth-largest investor, with 600 US companies employing about 143,600 people. In the context of 32% unemployment, this is considerable. Any deterioration in economic ties will significantly impact South Africa’s economy.

Points of contention:

- Land expropriation bill: Trump criticised this bill by stating that the US would cut off all future funding to SA until a full investigation into the issue has been completed. Others in Trump’s administration, like Secretary of State Marco Rubio, cited the new land expropriation law as one of the many reasons he is snubbing the G20 being hosted in the country.

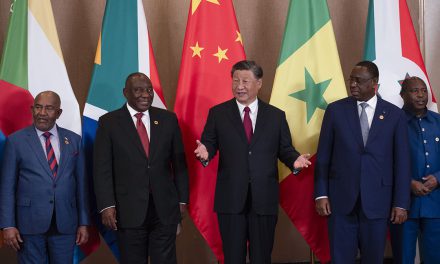

- BRICS: Russia, China, and Iran, one of the newest BRICS members, have strained relations with the US, and the US perceives SA’s strengthened relations with these countries as anti-Western.

- Lady R: The US was dissatisfied with SA’s decision to allow the US-sanctioned Russian cargo ship Lady R to dock in the Simonstown naval base in December 2022; it is still unclear what was loaded onto the ship.

- SA-China: Issues with China include establishing the private test flying academy in SA, which the US says recruits ex-American and North Atlantic Treaty Organisation pilots to train Chinese pilots.

- SA took Israel to the ICJ on the charge of genocide, which appeared to demonstrate to the United States that South Africa sympathised with the terror group Hamas.

A shift in US-SA relations

Before Trump’s presidency, tensions between the two states were already growing, one of the key points of contention being South Africa’s position on Palestine and Israel. Last year, there were threats to exclude South Africa from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which accounts for a significant portion of export access to US markets. Former Minister Naledi Pandor responded to this pressure by stating, “we will not be bullied,” particularly regarding calls to take a side in the Russia-Ukraine war.

South Africa maintains relationships with Washington’s geopolitical rivals, including Russia, Iran, and China, while simultaneously trying to preserve its economic ties with the US. These tensions escalated last year when the US House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs passed the US-South Africa Bilateral Relations Review Bill, which would require the government to undertake a comprehensive review of its relationship with South Africa, including re-evaluating the country’s participation in AGOA.

At the heart of this issue is Congress’s belief that South Africa’s foreign policy—driven by the African National Congress—no longer aligns with its stated commitment to non-alignment. Instead, Pretoria is perceived as increasingly favouring China and Russia, a stance that US policymakers argue undermines American national security and foreign policy interests.

What all of this means:

There is no denying that the US will continue to retaliate for perceived threats to US interests and security. One such measure is potentially withdrawing South Africa’s AGOA membership and the recent decision to boycott the G20 being hosted in South Africa this year. Notably, following this announcement, China and EU members extended their support to South Africa’s presidency of the G20.

Shifting focus from South Africa could push it toward stronger ties with both US adversaries and other developed nations. Aware of this risk, the Biden administration was reluctant to enforce measures like the review bill, fearing that alienating SA could drive it further into the Russia-China camp.

The US’s position can be interpreted in two ways:

- The US is making a clear statement that it is moving away from SA as a strategic partner

- This decision may force SA to make a pronounced shift, potentially moving away from its non-alignment stance.

An act of defiance?

During his State of the Nation Address (SONA), President Ramaphosa explicitly stated that “we will not be bullied”, reinforcing South Africa’s commitment to resisting external pressure. This stance aligns with its positions on AGOA, the Russia-Ukraine war, and engagement with US geopolitical rivals, emphasising sovereignty and strategic autonomy.

These tensions arise amid a shifting global landscape, where emerging and middle powers offer South Africa new opportunities to diversify economic and political partnerships. This push for a multipolar world strengthens South Africa’s role within BRICS and the Global South while reducing its reliance on Western ties. Countries like Japan, the EU, and Germany have increased engagement with Africa through initiatives like NAASP, FOCAC, and TICAD, positioning South Africa to align with alternative key players.

Given the US’s stated commitment to respecting Africa’s autonomy, as reaffirmed by Secretary of State Antony Blinken in 2022, singling out South Africa for its diplomatic choices appears contradictory. The US maintains strong ties with countries like Saudi Arabia and Turkey despite their engagements with Russia. Thus, US-South Africa relations should be framed within mutual respect for sovereignty and the right of nations to shape their own foreign policies.

South Africa faces the delicate task of managing its relationship with the US, as strained ties will not serve its national interests. Skilful diplomacy will be essential in navigating these challenges. While South Africa’s non-alignment stance is not new, leaders like Mandela and Mbeki effectively balanced diplomatic engagement with strategic autonomy. President Ramaphosa must now invest in a similar approach. As South Africa assumes the G20 presidency, it has an opportunity to strengthen ties with key global players such as the EU, Canada, and Mexico—nations also facing potential economic pressures from the US. Domestically, the Government of National Unity (GNU) must find greater alignment and adopt a united front to ensure a coherent and consistently applied foreign policy that serves national interests.

In its negotiations with the Trump administration, South Africa should aim to make strategic concessions that align with Trump’s domestic political priorities, demonstrating how cooperation could benefit his supporters. Ultimately, diplomacy will be the determining factor in the future of US-South Africa relations.

Dr Mmabatho Mongae is a Lead Data Analyst at Good Governance Africa (GGA), where she plays a key role in developing innovative, data-driven tools to improve governance and urban management across the continent. Her work includes the Governance Performance Index (GPI), a first-of-its-kind assessment of local municipal performance, and the African Cities Profiling Project, an initiative aimed at building a comprehensive information bank to assist cities in enhancing service delivery for both citizens and enterprises.

With a PhD in International Relations from the University of the Witwatersrand and as a research fellow at the Centre for Africa China Studies, Mmabatho’s work bridges rigorous academic research with real-world policy challenges. Her research has been published in respected platforms such as The Thinker, Journal of Public Administration, Routledge, and EISA Occasional Papers. She has also contributed thought leadership on democratic governance, energy transitions, and urban development in media outlets and policy forums.

Before joining GGA, Mmabatho lectured International Relations at Wits University for six years teaching courses on East Asia, South African foreign policy, International Political Economy, transnational Issues, and diplomacy.

At the core of her work is a commitment to ensuring that data and research translate into meaningful policy decisions, shaping more effective governance and development outcomes across Africa.