Africa: the data

The Africa Rising narrative is an example of how a number or a small set of statistics can be both informative and misleading

By Alfred Mthimkhulu

What does the data tell us? This can be a very encouraging question in a business meeting. It can mean that in principle, whatever was being discussed is worth further investigation: “Great, let’s just make sure we’re right!” On the other hand, it can be an understated expression of doubt: “This thing won’t work!” In essence, both interpretations wish that the data will confirm expectations. But it is also possible that the question is asked with a genuine desire to gain more knowledge so as to make an informed decision based on the results from data analysis. So the question, “What does the data tell us?” is, in most instances, a loaded one, and must therefore be addressed with care. This article reviews how some data analyses and interpretations have influenced the socioeconomic development narratives on Africa within the past decade.

Since analyses on economic development usually cover many variables—such as the quality of health and education, economic growth and political stability, among many others—the article will focus only on population demographics and quality of infrastructure. Africa’s demographics, especially its youthful population, are often cited as the foremost reasons for why the continent is an attractive investment destination. On the other hand, Africa’s infrastructure is mentioned as one of the main reasons why the continent struggles to attract investment and why it is difficult to do business in the continent. The Africa Rising narrative which has dominated media in recent years deeply engages both the population demographic and infrastructure issues, thus making the narrative a useful reference to anchor this article’s discussion.

Remarks by Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the IMF, in Maputo in May 2014 capture the essence of the Africa Rising narrative: “Sub-Saharan Africa is clearly taking off—growing strongly and steadily for nearly two decades and showing a remarkable resilience in the face of the global financial crisis.” However, it was perhaps Vijay Mahajan’s book, “How 900m African Consumers Offer More Than You Might Think” (2009), which heralded the dawn of the Africa Rising narrative in the media. In the preface to the book Mahajan wrote, “I have to admit that until a few years ago, I was guilty of overlooking Africa…Like most scholars in the developed world…I saw Africa more as a charity case than a market opportunity. I was wrong, and this book is here to set the record straight.”

In a recent report in the Financial Times, Vijay Mahajan reveals that inasmuch as he still stands by his bullish outlook on Africa, the title of his book was a “concoction” by the publisher. The catchy part of the title is arguably the number: 900 million; in 2015 this had grown to just over a billion. What business would let such a huge market go untapped? And so the Africa Rising narrative caught on. But the figure of 900 million people can be as misleading as it is attractive to investors. A business exploring new markets is not interested in just the total population of a territory but the population’s capacity to pay for goods and services. In 2009, when Vijay Mahajan’s book was published, closer to zero than 1% of the approximately one million Mauritians were living on less than the then-poverty line of $1.25 per day.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, with a population of 62 million and the second largest country by land area in the continent, about nine in ten people, or 88% of the population, lived below the poverty line. Such realities of poverty could have motivated economists at the African Development Bank (AfDB) to estimate the proportion of the middle class in the then 900 million Africans. Unlike those living below the poverty line, the middle class, by definition, has money to spend. Loosely defining the middle class as people living on between $2 and $20 per day, the AfDB economists arrived at 355 million people or a third of the total population as being middle class. These 355 million people could be considered a viable consumer market to target. The rest would require support from governments and other humanitarian efforts. But then other researchers countered the AfDB economists’ rather loose definition of the middle class.

They tightened it up a bit and came up with figures ranging from 15 to 18 million Africans qualifying as middle class. These numbers are a far cry from the ideal consumer market being the same as the total population. Nevertheless, these lower figures are gaining some credibility as some multinational businesses scale-down operations in some African markets because of thinner-than-expected trading volumes. Estimates of the size of Africa’s middle class are not only useful for gauging the purchasing power of the African consumers. The size of the middle class is also indicative of the social and political stability of a country, since historical evidence from other parts of the world suggest that the middle class is the backbone of civil society and that civil society is a necessary constituent for an enduring democracy. The larger the civil society, the better for democracy and good governance.

In sum, although equating total population to the overall consumer market in Africa may have been inherently misleading, subsequent analyses have generated very informative debates and increased our understanding of Africa’s growth trajectories. An example is Morten Jerven’s book “Africa: Why Economists Get it Wrong”—a critique of how economists have assessed Africa’s economic growth over the decades. He argues that Africa has experienced growth spurts before, and that the recently-observed high growth rates referred to by the Africa Rising narrative are “to some extent old news” driven quite significantly by the commodities boom. Another important aspect that has been raised by some economists is the need to be more curious about economic productivity of each country than whether or not Africa is rising.

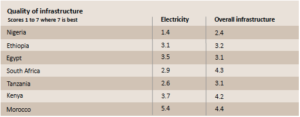

Economists such as Robert Kappel, in a paper titled “Africa: neither hopeless nor rising”, seek to determine and understand attributes of countries that seem to explain higher productivity, as well as whether countries lacking such attributes can be assisted. This approach was echoed by Christine Lagarde at the Maputo Africa Rising Conference, where she noted that the “tide of growth” had not lifted all countries. This makes it important to understand why some countries are lagging. Infrastructure is one of the main areas of concern when discussing investing in Africa and is often cited as an explanation for performance differentials between countries. Let us suppose that the total population of a country is the only useful variable for attracting investment, as in the 900 million consumer market conception. In that case, countries listed in the table below would be of particular interest, given that they have some of the largest populations in Africa.

The table lists scores on the quality of electricity supply and the overall infrastructure, where the best possible score is seven. Nigeria, which is the most populous country in the continent, has a score of 1.4 out of a possible 7 on electricity and 2.4 for the overall infrastructure. Morocco has some of the best ratings on infrastructure in the continent but even then, its scores well below 7.

Source: World Economic Forum; Africa Survey, GGA

These infrastructure deficits present significant investment opportunities in the sector. As a study by the consulting firm McKinsey & Company estimates, Africa must spend about $35 billion per annum on electricity infrastructure to meet demand by 2040. But how we understand this information, and in what context, can shape the way we use it. As we have seen, the continent’s youthful population is often highlighted as a potential strength, but it is also true that Africa’s high levels of youth unemployment are worrying. Taken together, the continent’s demographics and the infrastructure deficits make a strong case for large and labour intensive infrastructure projects that can offer opportunities and impart skills to the youth. Such projects can unlock Africa’s next growth phase in and at the same time, counter the continent’s potentially explosive issue of youth unemployment.

Alfred Mthimkhulu leads the quantitative analysis function at GGA. A former investment banker, Alfred received his PhD from the University of Stellenbosch Business School.