Africa and wars: traditional weapons

The advent of the machine gun at the end of the 19th century irrevocably changed the way wars were waged in Africa

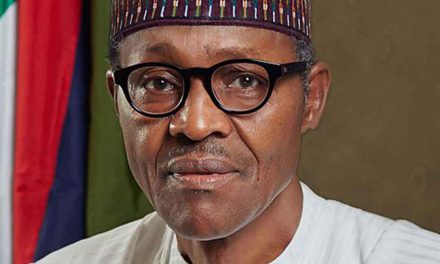

Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini demonstrates the use of the .308 rifle, which has replaced the traditional spear for Zulu royal warriors, during the revival of the age-old hunting ceremony that began with King Shaka. The two-day event, revived after two decades, was held at Hluhluwe, some 350 km north of Durban in KwaZulu-Natal in 2001. Photo: RAJESH JANTILAL / AFP

“Whatever happens, we have got the Maxim gun, and they have not,” wrote Hilaire Belloc, British writer and poet, in his essay, ‘The Modern Traveller’ in 1898. He was writing at the peak of the European powers’ empire building and the Maxim, a revolutionary machine gun that could fire 600 rounds a minute, was the ultimate weapon for the “pacification” of “hostile” tribes. Just a decade later much of Africa would consist of colonies or protectorates of European powers. For centuries African weapons had been used for offence, defence and game hunting, and they had undergone transformation to suit contemporary needs – but they were no match for the Maxim gun. African weapons stood no chance against a gun that spat volleys of bullets and thundered like lightening during a tropical rainstorm.

A general assessment of weapons and war strategies on the continent before the anomie created by external influence, which took root during the slave trade and colonial conquest, depicts a continent that had wars but with comparatively few war-related deaths. Cultural factors – a lack of sophisticated arms, small populations, thick forests, vast savannas and deserts, long unnavigable rivers, and health and ecological challenges – all conspired to limit the losses warring communities could inflict on each other on the battlefield. Allan Chore, a lecturer at Kenya’s Garissa University, who is also a PhD candidate exploring the African art of war, says precolonial African weapons fell into two main categories – close combat and mid-range. Close-combat weapons, he explains, included swords, clubs, arrows, knives, daggers, axes and crowbars.

Mid-range weapons comprised of projectiles such as spears, slings, bows and arrows. Each community, he says, had a certain weapon that was associated with it. Andre DeGeorges in his 2012 article ‘African Traditional Hunters and Their Weapons’ agrees with Chore’s observation, but adds that the hand-made aspect of African weaponry also involved a degree of artistry and identity. “Weapons conveyed not just the ingenuity of their makers, but also their role and artistic abilities, which in turn brought out the ethnic identity of their makers and their users,” he argues. In terms of tactics, Chore says that war skills, terrain, the nature of war and strength of the enemy dictated the methods employed in fighting. He questions the often-repeated idea that African communities have never had war strategies.

The Maasai and Nandi of Kenya’s Rift Valley used bows and spears against the British in the 1890s-1900s because the high ground of the escarpment offered them an advantage when targeting the enemy below, for example. The Zulu, like the Maasai in Kenya, were considered “fierce fighters” by Europeans, and they mastered close quarter combat techniques, preferring a short spear known as the assegai. The Fulani of northern Nigeria, the Berbers of North Africa and communities in the Horn of Africa had cavalry when they adopted horse breeding from the Arabs, adds Chore. Osarhieme Benson Osadolor, in his study on ‘The Military System of the Benin Kingdom’ (2002), noted that iron technology led to the development of weapons that impacted on the character of war in the region.

“In West Africa, the states that rose to power in the period between 1400 and 1700 such as Benin, Nupe, Igala and Oyo dominated others partly because of the advantages in the development of iron technology,” writes Osadolor. Similar views are expressed by Chore, who adds that most communities lacked formal training for fighters, although training did take place. “Since there were no military academies, fighting skills were imparted through games, drills, physical fitness during ceremonies and also through game hunting,” he says. According to Chore, African philosophies guided the rules of warfare. So, for example, the women and children from communities that lost a war were usually not killed. Combatants and members of communities that lost a war were usually taken prisoner, and assimilated.

“What might surprise many, is that wars were also fought as a sport,” he told Africa in Fact. “Young men, especially in pastoralist communities, would raid neighbouring communities, without the blessing of elders, to acquire cattle for use as a dowry.” David Neville Masika, a peace and conflict studies lecturer at Kenya’s University of Nairobi, says African warfare was organised and guided by elders to conform to traditions. War was governed by traditional constraints, he says. Like Chore, he argues that combatants in most communities were barred from violating women and hurting children. “Fighting wasn’t supposed to take place where women and children were; no wonder it was a taboo to wage war at night,” he says. Select groups possessed the art and science of weapon making and secretly guarded their skills, says Masika.

“African weapons have always undergone transformation,” he says. “Take the case of the Zulu people, who opted for shorter spears after realising that, unlike long spears, they could be used without having to be thrown at enemies, hence minimising battlefield losses.” Other improvements included the use of poison on weapons to render them more lethal. In his 2013 article, ‘Weapons in African Art’, Andrew Keet points out that while African war was often a serious business, weapons were also an avenue for artistry and self-expression. “Weapons would be decorated with intricate designs. The handles of daggers and axes, for example, became an art form as soldiers took pride in the weaponry that would defend their land and people,” writes Keet. With the arrival of European arms on the continent, Africans were quick to note the comparative weakness of their weapons, says Chores.

As part of compensating for this, communities developed the ability to mobilise fighters quickly on a battlefield while devising ingenious methods to counter European armies. “The Zulus used the ‘horn formation’ against the British and Boer armies, while the Maasai and others in East Africa used ‘multiplicity or massing’ in the battlefield, literally overwhelming the enemy, and thus compensating for their ‘weak’ weapons by wearing down the enemy for possible retreat,” he says. John Laband, historian, retired history lecturer and author of The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Nation says that the type of weapons used by traditional African societies could vary enormously from one society to another and from period to period. African communities worked continuously to improve their weapons, with changes inevitably occurring over time, he told Africa in Fact.

Variations in types of weapons depended on a range of factors, including geography, the seasons and the reasons behind any war. Chris Peers, writing in his book Armies of the Nineteenth Century. East Africa: Tribal and Imperial Armies in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, 1800-1900, argues that the types of weapons used by some communities were, in themselves, deterrents to the widespread killing of combatants. Peers quotes the British explorer Joseph Thomson, who visited the Kavirondo region around Lake Victoria in the late 19th century, describing the spears of tribesmen as long with small heads and inherently less lethal. Thomson wrote that combatants also aimed at avoiding getting too close to each other.

“It’s at once seen from their weapons, that they are not warlike people, their spears being of the very poorest with small heads and handles commonly eight feet long, as if they had no desire to get into close quarter with the enemy,” said the explorer. Some African codes of war were so deeply ingrained, Peers writes, that the Karamojong of northern Uganda, who were known as fierce fighters, were were shocked at the inhumanity of African opponents using machine guns in the late 19th century. The Karamojong warriors went into battle yelling war cries based on the names of their oxen, but fell apart on encountering an enemy armed with guns. And after the battle they were less concerned at the huge human losses than they were that their enemy had not offered them a chance to perform their ritual taunting before the battle. Once guns were introduced into Africa, communities incorporated them into their battle strategies.

Necessity being the mother of invention, Chore says, African communities even started making homemade guns. But, as Masika says, no African societies had weapons of mass destruction. Communities, while at war, were forbidden from poisoning water sources out of consideration for women and children. “War atrocities were rare,” says Masika. “An exception was the era of King Shaka of the Zulus, whose philosophy of ‘revenge’ destabilised communities in southern Africa and beyond.” Yet, despite possessing the assegai, arguably a “superior weapon”, even the Zulus did not generally annihilate the communities they defeated in battle, preferring to displace or assimilate them.

Justus Wanzala is a Kenyan journalist who writes on the environment, climate

change, agriculture and practical technologies as well as sustainable development and social issues. Currently, he works for the Kenya Broadcasting Corporation and as a freelancer/contributor for various publications across the globe.