In mid-July, we witnessed extensive looting and violence in South Africa, concentrated in some parts of Gauteng and the eastern KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) provinces. The unrest claimed over 300 lives and thousands of businesses were looted and, in some cases, burned down. The biggest loss apart from the loss of lives is the loss of jobs, income and livelihoods. According to several industry groups, it may take some businesses several years to rebuild.

In mid-July, we witnessed extensive looting and violence in South Africa, concentrated in some parts of Gauteng and the eastern KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) provinces. The unrest claimed over 300 lives and thousands of businesses were looted and, in some cases, burned down. The biggest loss apart from the loss of lives is the loss of jobs, income and livelihoods. According to several industry groups, it may take some businesses several years to rebuild.

The preceding context to the looting was already concerning. South Africa is in the throes of an unemployment crisis, with at least 32.6% of South Africans jobless in the first quarter of 2021. For young people, the unemployment picture is more distressing with a reported 46,3% of the youth unable to find work. These alarming statistics, coupled with the anticipated aftershocks from the recent social unrest, does not bode well for immediate redress for the affected sectors of society. The root causes of the unrest have been attributed to many different factors competing for explanatory ascendancy.

On the one hand, it is understood that the catalyst was the arrest of former president Jacob Zuma related to him defying an inquiry into high-level corruption allegations during his nine-year tenure. Due to Zuma’s refusal to appear before the Zondo Commission of Inquiry into State Capture, the Constitutional Court sentenced him to 15 months for contempt of court. As a result of Zuma’s imprisonment, his supporters mobilised and barricaded major roads in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal to create instability, which resulted in disrupting supplies of food, fuel and medicine. This instability spiralled into rioting and the looting of thousands of shops. Worryingly, it also affected the Covid-19 vaccination programme as well as other health services.

On the other hand, the trail of destruction through extensive vandalism and looting is attributed to high levels of criminality. More than that, South Africa is still battling with issues of poverty, inequality, unemployment, and hunger, all of which have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Combined, these factors provide a relatively comprehensive account of the causes of looting. In this respect, a recent research study confirms that collective violence and looting is often a consequence of multiple root causes. Socio-economic exclusion and systematic inequality are clearly part of the driving forces that tempted some South Africans to join in the looting and vandalism of shops, shopping centres and malls, and distribution warehouses.

The economic impact of the civil unrest

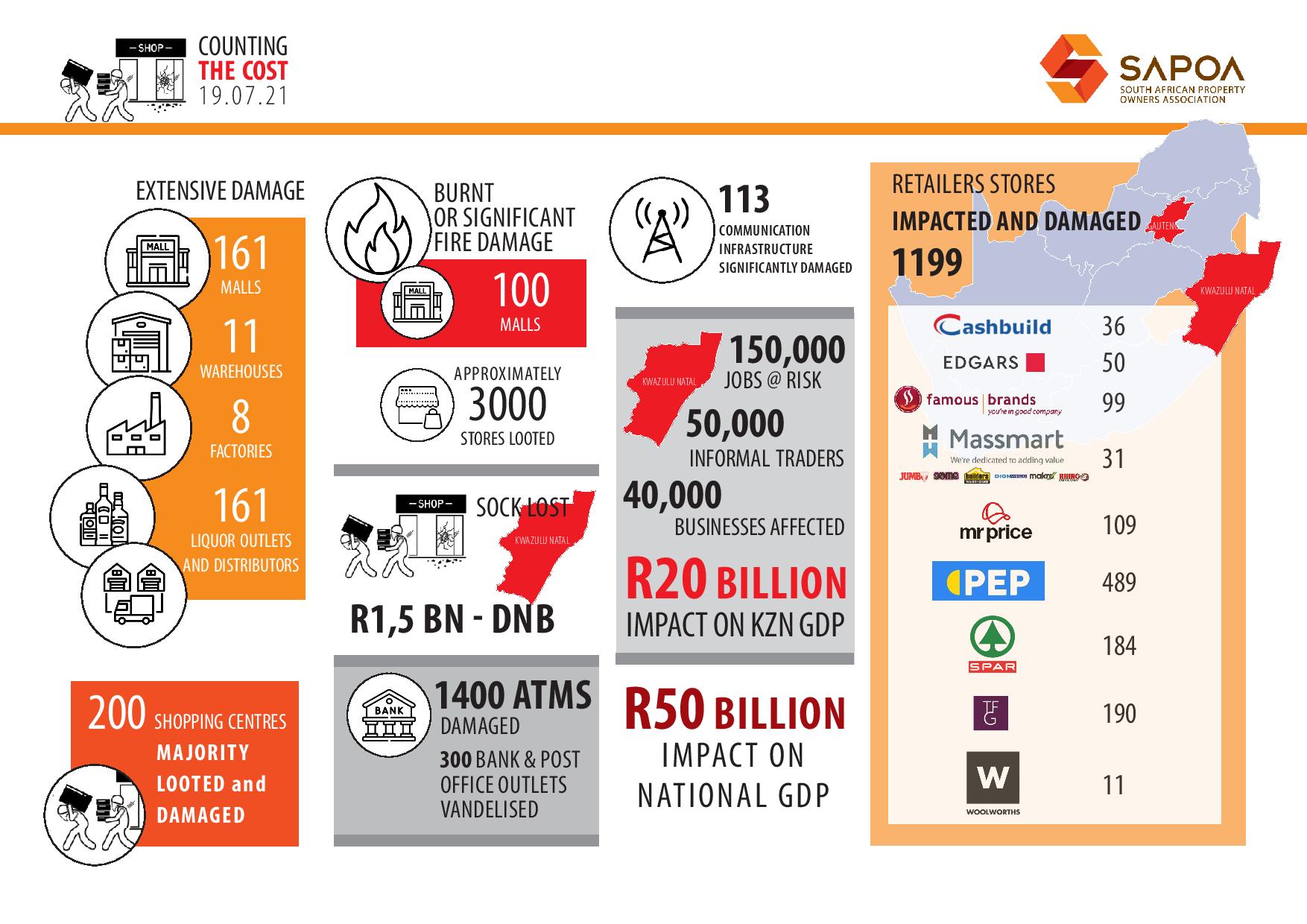

The events of July 2021 can be described as one of the worst incidents of civil unrest in the history of post-apartheid South Africa. The economic impact was most evident in Africa’s biggest container port in Hammarsdale, Durban, where looters targeted many retail warehouses and manufacturers. The estimated cost to KZN’s gross domestic product (GDP) in terms of damage to property, lost exports and losses to stock was approximately R20bn (equivalent to US$1.4bn).

The South African Property Owners Association (SAPOA), a representative body of the commercial property industry in South Africa, published the below detailed infographic highlighting the impact and damage the looting has had on South Africa’s economy and infrastructure. In summary, as of 19 July 2021, SAPOA estimated that the cost of the unrest at R50 billion to national GDP. Additionally, 1199 retailer stores were damaged and 150 000 jobs were at risk in KwaZulu Natal alone. SAPOA further estimated that 113 sites of communication infrastructure, including network towers and community radio stations, were significantly damaged.

The role of community interventions in times of crisis

Despite the significant damage that resulted from the looting and destruction of many businesses and infrastructure, we observed many concerned South Africans in potentially targeted areas in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal standing together to safeguard businesses and spaza (informal) shops in their respective communities. This element of the response has been under-reported and is important to analyse.

The Kasi Brothers is a brotherhood group that started in January 2021 that aims to promote cooperation and peace among men of Atteridgeville, a community west of Pretoria. The group took it upon themselves to safeguard the malls in their community by taking shifts. The Kasi Brothers expressed that the looting was a crime and outright condemned the violence and destruction.

Residents and business owners of Eldorado Park, a community in Gauteng, united to prevent the looting from spreading to their community. Infrastructure was protected by approximately 150 community members by forming a human shield around properties and they managed to successfully safeguard the business district.

Community members of Pimville in Soweto also participated in protecting Maponya Mall alongside the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) and South African Police Services (SAPS).

In Kliptown, small groups of local people tried to stop looters clearing out local food shops. Nkotozo Dube, 36, a former tourist guide in Kliptown, claimed: “We did our best to protect our community but there were just too many people. They just pushed us away. We never saw the police. It’s going to be really hard now … really tough just to eat.”

In an attempt to stem the threat, other residents set up makeshift barricades to block access to their neighbourhoods, or stood guard outside malls and other businesses. In some parts of the city of Durban, which has been hit badly by the disturbances, residents were reported to have concluded informal agreements to act as “backup” for police.

In Mpumalanga, residents including taxi operators spent the night at the Emoyeni Mall at the Pienaar township outside White River. This community effort was led by Mandla Msibi, Mpumalanga MEC for agriculture, rural development and land affairs. Subsequently, we observed the #NotInMyCommunity and #NoToLooting movements gain momentum on social media platforms and create further awareness of the preventative measures that were initiated and led by community members on the ground. More importantly, many concerned South Africans mobilised to clean up the streets of the targeted areas and have participated in initiatives such as #SowetanRebuild to begin the process of restoring small businesses.

Contrary to popular expectations, taxi associations in different parts of the country also geared up to protect businesses amid the widespread civil unrest. The South African National Taxi Council (Santaco) in Tshwane directed all taxi associations in the region to “go out in full force” to protect all shopping malls in the city. On 13 of July 2021, Abner Tsebe, the chairperson of Santaco said,

“The taxi industry in Tshwane has taken this position in anticipation of the events in Joburg City spiralling to Tshwane. The leadership of the industry strongly warns those with intentions to loot to desist from any attempts as they will find the industry waiting.”

Santaco has been applauded by many for deploying members to protect malls in Tshwane, although the move was also criticised by others.

In the absence of SANDF and SAPS in some of the areas that were affected, community intervention played a significant role in preventing looting and destruction. This revealed the importance of uplifting and acknowledging community governance in times of crisis.

The strength of community governance evidenced above indicates a critical mass of citizen voice and empowerment that not only protects communities but can also be harnessed to hold the state to account more robustly. This active citizenry is critical to upholding the ends of good governance, especially at the local level.

Pledging to Good Governance

At Good Governance Africa, we define good governance as the authoritative allocation of resources in a fair and equal manner. In the spirit of rebuilding South Africa – both the economy and society, we call on South Africans to pledge their commitment to the good governance of the country. Beyond that, we call on all African citizens to pledge allegiance to the good governance of our continent and promote the dignity of all African people. In concluding, South Africa’s active citizenry has banded together against the threat posed by looters who would see the country reduced to ruin. This positive force is a shining outcome in the midst of these recent dark events, and points to the need for citizens to pledge to seeing Good Governance become a reality for our nation.