On 24 August, coinciding with a controversial election being held in neighbouring Zimbabwe, the latest BRICS summit concluded in Johannesburg.

The BRIC acronym was originally coined by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill in 2001. Original member countries developed a formal bloc comprising Brazil, Russia, India and China in 2008 on the sidelines of a G8 meeting. Russia was subsequently expelled from the G8 after its invasion of Crimea in 2014. South Africa was invited to join BRICS in 2010 and formally integrated by 2011.

(From L to R) President of Comoros Azali Assoumani (L), South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, President of China Xi Jinping, and Senegalese President Macky Sall attend the China-Africa Leaders’ Roundtable Dialogue on the last day of the 2023 BRICS Summit in Johannesburg on August 24, 2023. Photo by ALET PRETORIUS /AFP

In a 2017 article for the Council on Foreign Relations, Alyssa Ayres indicated that the group encapsulated the rise of emerging markets but that it was “less clear whether this grouping also provides durable common interests for a multilateral organisation, especially given the vast economic differences among the five”. Ayres went on to note that the political differences between members were also sharp.

By 2017, the bloc could claim some significant achievements, including its own institutions such as the New Development Bank. The original impetus was — and remains — to ensure more of a voice for emerging economies in a world dominated by the United States; a voice in governing the institutions that affect the whole world.

Earlier this year, for instance, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva demanded to know why the BRICS countries were hinged to the US dollar and strongly suggested a move towards trading in home currencies instead.

Michael Pettis, writing in Foreign Affairs, concurred that there is a downside to a dominant US dollar. Nonetheless, “adopting an alternative global reserve currency will not necessarily benefit surplus countries such as Brazil. Rather, it will force them to confront the reasons for their surpluses — persistently weak domestic demand based on a very unequal distribution of domestic income — and address them by cutting back on production and redistributing income.”

Aside from the economic difficulties of moving away from a dollar-dominated world, the political differences between the bloc appear to be of greatest concern.

The 2023 BRICS conference was marred in advance for South Africa by the question over whether we would have the courage to arrest Vladimir Putin, the Russian dictator if he attended in person. We are a signatory to the Rome Statute, which governs the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC has issued a warrant for Putin’s arrest, given apparent evidence of war crimes in Ukraine. South Africa failed to arrest Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir, another wanted war criminal, back in 2015. In the end, after careful diplomatic maneuvering, Putin stayed at home.

South Africa’s dalliance with Russia has raised eyebrows at home and abroad, not least with the US, which appeared to threaten a termination of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) trade benefits, in which export benefits alone amount to roughly R60 billion a year.

AGOA provides member countries with legally sanctioned access to American markets that it would otherwise struggle to attain. The US ambassador to South Africa went so far as to publicly assert that arms to aid Russia’s war effort in Ukraine were loaded onto Lady R, a Russian ship that docked in Simon’s Town in December 2022. Whatever one believes about that incident, it appeared that the left hand had no idea what the right hand was doing — the defence minister said there was nothing (though she used more colourful language) on the ship, but the president ordered an inquiry into the matter nonetheless.

These incidents raised questions about the integrity and sensibility of South Africa’s foreign policy, just as the BRICS summit has done.

The BRICS countries concluded the August summit by formally admitting Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to join the group from the beginning of 2024.

This raises a question, politically, of shared and common values. China’s President Xi Jinping would like to see the expanded BRICS group become a substantial challenger to the G7, but the G7 is likely to retain its dominance for the foreseeable future because of its shared and common values. Relatively equal income distribution and the sheer strength of the G7 economic engines mean that the BRICS+6 challengers have a mountain to climb.

Politically shared values really matter in climbing this mountain, because the economics literature has arrived at as near a consensus as economists ever will that institutions matter for development.

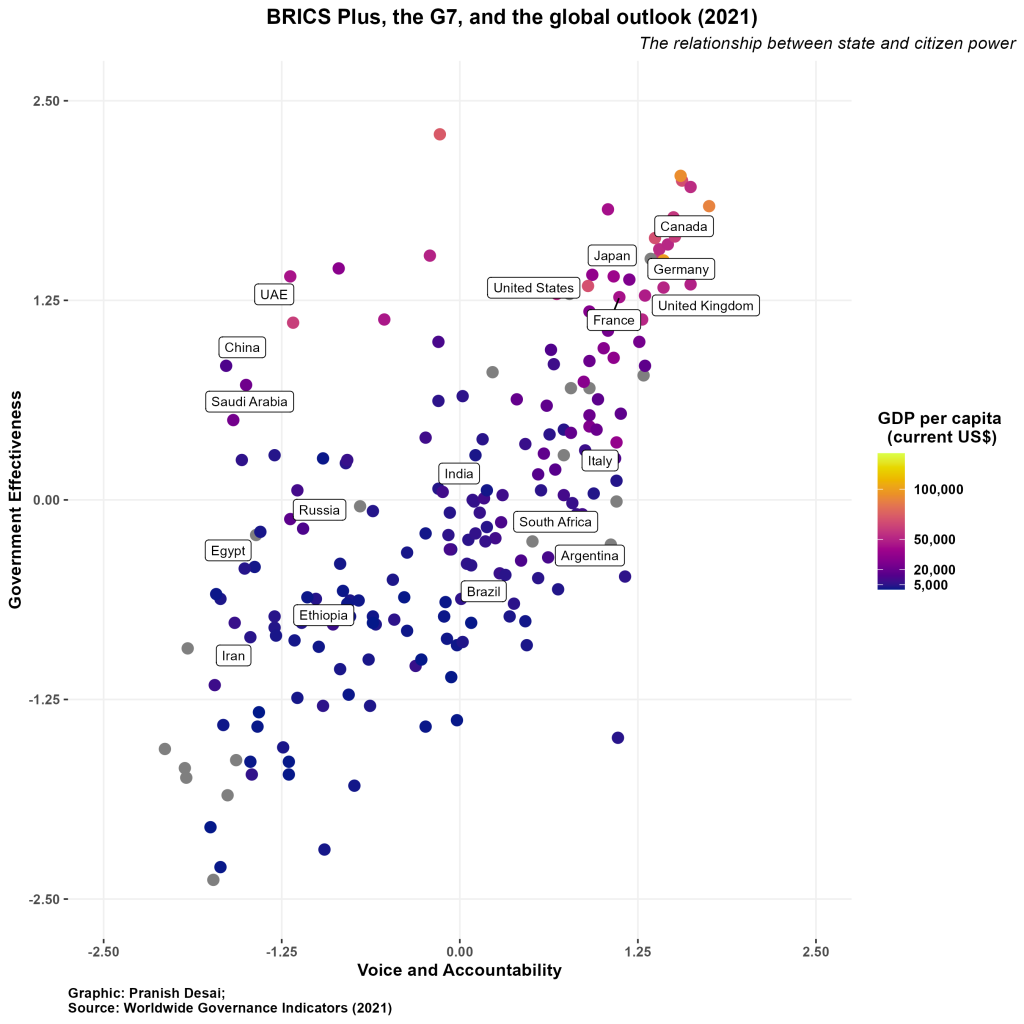

Institutions are the social systems — norms, beliefs and values — that motivate regular human behaviour. If they are strong, they drive economic growth sustainably. To be strong, government effectiveness must grow in strength and sophistication alongside citizen power. Citizens must be able to hold their governments to account, lest Leviathan become unshackled. To measure this at GGA, we built a governance coefficient that shows how government effectiveness combines with citizen voice to drive economic prosperity. The visualisation below locates the G7 and BRICS+6 countries within the overall global context across these variables.

China is probably in for a hard landing because its citizens don’t have a voice, and income distribution remains highly unequal. There is little economic dynamism driven by the private sector. Moreover, rapidly declining fertility rates are a problem for future economic productivity (a problem the G7 also faces). State dominance also means that the information officially released is untrustworthy, or at least at odds with private sector data. I draw attention to this because China is clearly the dominant partner in BRICS, and scholars warning of the other members being subject to Chinese ambitions should be heeded. Moreover, countries hoping for economic salvation through banding to China should be careful. Its “economic miracle” will probably prove short-lived, as extraordinary as it has been.

This brings us to what South Africa is thinking. Our ruling party has hooked the country’s wagon to a set of countries with whom it officially has little in common. Aside from Ethiopia and Argentina, the other additions to BRICS+6 are high on oil-fuelled liquidity and low on sustainable economic engines for diversified growth. None of them have an honourable human rights record. The preamble to South Africa’s Constitution states the following:

“We, the people of South Africa, … through our freely elected representatives, adopt this Constitution as the supreme law of the Republic so as to … lay the foundations for a democratic and open society in which government is based on the will of the people and every citizen is equally protected by the law … Build a united and democratic South Africa able to take its rightful place as a sovereign state in the family of nations.”

On a values level, this is fundamentally at odds with China, Russia, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Building partnerships with countries who eschew citizen voice seems to be sacrificing principle for pragmatism and ultimately compromising our chances of being able to generate broad-based development.

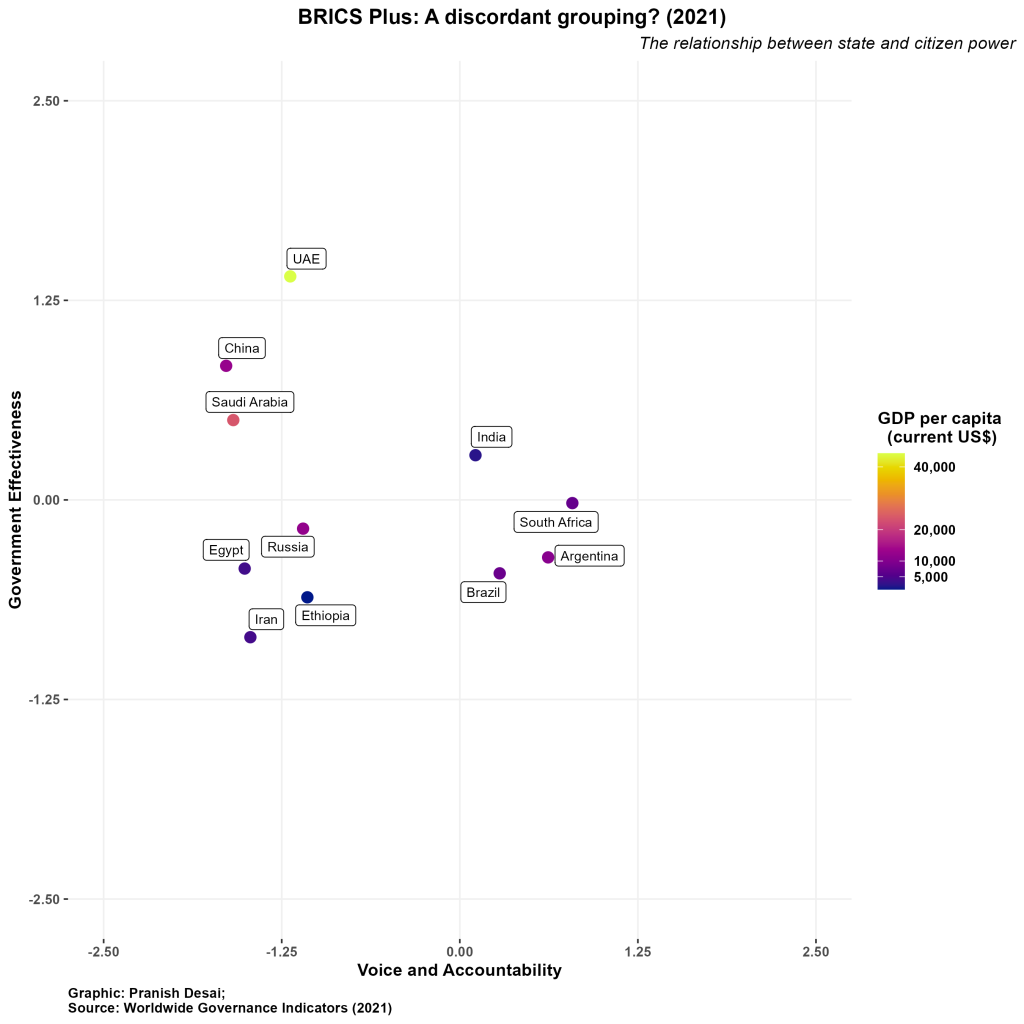

Going back to our Governance Coefficient, consider the following data and graphic with only BRICS+6 countries represented:

- By 2021, China scored 0.84 (on a scale of -2.5 to 2.5) on government effectiveness. It scored -1.64 on citizen voice — one of the lowest recorded figures in the world.

- In the same year, Saudi Arabia scored 0.5 on government effectiveness and -1.59 on citizen voice.

- Iran scored -0.86 on government effectiveness and -1.47 on citizen voice. According to Iran Human Rights, 483 people in the country have been executed in 2023 alone, while 582 people were executed in 2022. Many of the charges are allegedly trivial and executions used to maintain power through fear.

- Egypt scored -0.43 on government effectiveness and -1.51 on citizen voice.

- The UAE scored 1.4 on government effectiveness (among the highest in the world, to be fair), but -1.19 on citizen voice.

These countries do not exemplify good governance. South Africa, by way of contrast, scores -0.02 on government effectiveness (significantly down from its 1996 position of 1.02) and 0.79 on citizen voice in 2021. Partnering with questionable regimes appears to run against the grain of our political and economic interests. – Craig Moffat and Pranish Desai contributed to this analysis.

Dr Ross Harvey is a natural resource economist and policy analyst, and he has been dealing with governance issues in various forms across this sector since 2007. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town, and his thesis research focused on the political economy of oil and institutional development in Angola and Nigeria. While completing his PhD, Ross worked as a senior researcher on extractive industries and wildlife governance at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), and in May 2019 became an independent conservation consultant. Ross’s task at GGA is to establish a non-renewable natural resources project (extractive industries) to ensure that the industry becomes genuinely sustainable and contributes to Africa achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ross was appointed Director of Research and Programmes at GGA in May 2020.