View taken on October 4, 2016 in Jwaneng, shows the Jwaneng mine of Debswana, the world’s leading producer of diamonds by value in Botswana. / AFP PHOTO / MONIRUL BHUIYAN

Good governance structures, not the natural-resource ownership model, are key to ensuring successful social and economic outcomes in several sub-Saharan countries

Natural-resource governance refers to the management of natural resources with a particular focus on how governance affects the quality of life for both present and future generations. Natural resources have been the leading source of revenue for several countries in post-colonial sub-Saharan Africa.

However, one of the most surprising features of modern economic growth in the region is that the majority of economies with natural-resources wealth tend to grow more slowly than those without substantial natural resources. Countries whose economies are dominated by natural-resource revenues often fail to live up to the expectations their immense natural-resource wealth inspires. One third of the world’s poorest people live in natural resource-rich countries.

In the past 30 years or so, the world’s star performers have been the resource-poor, newly-industrialising economies of east Asia (Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore). Meanwhile, many resource-rich economies, including the oil-rich countries of Mexico, Nigeria and Venezuela, have gone bankrupt. The “Dutch disease” (the negative impact on an economy of anything that gives rise to a sharp inflow of foreign currency, such as the discovery of large oil reserves, according to the Financial Times) and the “resource curse” (the failure of many resource-rich countries to benefit fully from their natural-resource wealth –The Natural Resource Governance Institute) theories have tentatively explained failures of natural resource-rich economies.

Most experts believe that the abundance of resources creates governance-related problems such as rent-seeking, corruption and political violence. But the impact of the discovery and exploitation of natural resources is not, by itself, either a curse or a blessing. If well managed, resource wealth can support socio-economic development. Appropriate governance and ownership models are thus key in this regard, since they determine how resource revenue is managed.

Ownership models can be broadly categorised as those centering on state ownership, private ownership, and joint ventures between the public and private sectors. Each of these categories entails different levels of state involvement in resource wealth management. That is to say, the nature of the prevailing political system generally influences a government’s choice of ownership structures.

Authoritarian regimes usually prefer state ownership models, which increases the probability of negative developmental outcomes. In contrast, more open and transparent political systems are more likely to adopt ownership structures that entail limited state shareholding, such as public-private partnerships (PPPs) that usually result in more favourable developmental outcomes. In this connection, it will be useful to examine how three different PPP models have fared in Botswana, Angola and Zambia, respectively.

Botswana is a notable example of a joint venture. The country, far from suffering from the resources curse, is a functioning and peaceful state that has an unbroken history of free and fair elections, combined with the highest economic growth rates globally for the past few decades since obtaining independence in 1966. Initially, there was some scepticism about its prospects as an independent nation, as it was very poor and undeveloped. The country’s second president, Ketumile Masire, in a public lecture at Santa Clara University in California, on October 20, 2005, said, not for the first time: “When we asked for independence, people thought we were either very brave or very foolish”. It was, indeed, unbelievable that a poor country like Botswana would ever be described as an African economic success. But it is, thanks to De Beers’ discovery of diamonds in the country.

The modern history of Botswana is closely linked to the story of diamonds. This, in turn, is linked to the story of the 50-50 joint venture partnership, Debswana, formed in 1969 between Botswana’s government and De Beers. Debswana, one of the world’s most enduring public-private partnerships, is a good example of Botswana’s semi-directed model of mining regulation.

Under this model, the government collects substantial mining revenues from the project, which it invests in social spending; this is managed by a transparent and accountable governance structure. The government also uses its regulatory role as an equal partner to integrate the mining sector into national development plans.

The partnership has resulted in political stability, continued good governance and careful investment of revenues in the long-term development of infrastructure and human capital. In other words, Botswana has managed to translate its work on extractive governance into tangible and measurable social progress. The average GDP growth rate since the 1980s has been 7.8%, about 40% of which can be attributed to mining.

Mining has increased Botswana’s revenue from less than P10 million (about $961,847) a year at independence to over a billion by 2002. When diamonds were discovered in Botswana in 1966, there were only three secondary schools; today, due to revenues from diamonds, there are more than 300. Children from 6 to 13 years old receive free schooling. Secondary education is 95% funded by the government, enabling children to stay in school longer. Furthermore, approximately 25% of the labour force in Botswana is directly or indirectly linked to diamonds, and this figure is set to rise.

At a Good Governance Africa (GGA) workshop on risk, extraction and ethics in November 2016, it was agreed that a government’s will to invest resource revenue in the interests of its people is key to successfully linking natural-resource wealth to social and economic development. This has been the case in Botswana. At a Diamond Trading Company gala dinner in June 2006, Festus Mogae, then president of Botswana, said: “For our people, every diamond purchase represents food on the table; better living conditions; better healthcare; potable and safe drinking water; more roads to connect our remote communities; and much more.”

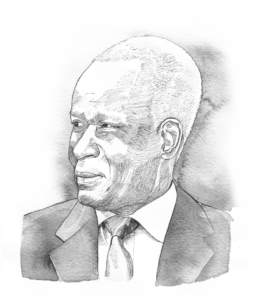

Angola is a notable example of state ownership with control. President Eduardo dos Santos ran an authoritarian regime, with the expected model of regulation, as well as the predictable outcomes. The government is fully involved in the management of the country’s resource wealth – with minimal transparency and unimpressive developmental outcomes.

Former Angolan President Eduardo dos Santos Illustration: Vusi Malindi

Angola’s oil sector is capital intensive with relatively few actors, which is perhaps one reason behind the government’s authority over natural-resource revenue. The Sociedade Nacional de Combustíveis de Angola, commonly known as Sonangol, has been the leading national institution in Angola’s petroleum sector since the end of the country’s 27-year civil war in 2002. Established in 1976, the national oil company plays a key role in managing the country’s oil sector, conducting some operations itself and gaining operational expertise from foreign operators through joint ventures.

The main contractual agreements Sonangol uses in its associations with other companies are joint ventures and production-sharing agreements (PSAs). Under joint ventures, the government cedes ownership of the oil to the companies in return for royalty payments and income taxes. In PSAs, the ownership of the oil remains with the government, while the companies function as contractors to Sonangol. The majority of oil contracts in Angola are covered by PSAs.

However, despite Angola’s significant oil-sector revenue, half of the population still lives below the poverty line and many are without access to basic services such as proper water, infrastructure, education, medical care, sanitation and electricity. The UNDP’s Human Development Index ranked Angola 150th out of 188 countries in 2016 and it is among 20 countries with the highest infant mortality rate.

During the decades since it was established, Sonangol and the country’s government and political-economic elite failed to reinvest proceeds from the oil sector in the development of a more diversified economy and a vibrant human capital base. The resultant lack of capacity remains a key challenge even as Angola has emerged as a major economic power in Africa.

Transparency and accountability within the oil sector remains very weak. Transparency International (TI) ranked Angola 164th out of 176 countries in its 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index. In March 2012, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that $32 billion had disappeared from the country’s public accounts between 2007 and 2010. Institutionalised corruption has become structural in the political system, with networks of loyalty being essential to its survival.

By contrast, Zambia is a notable example of the private-ownership model. The Zambian mining sector has undergone three phases (privatisation, nationalisation and privatisation) since independence, and this fact is relevant to understanding its approach to natural-resource governance.

For the past two decades, Zambia’s mining sector has experienced significant foreign investment, driven mainly by the privatisation of state-owned Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM). Since 2003, once unprofitable copper mines have been recording huge profits, thanks to favourable tax concessions negotiated at the time of privatisation.

Fresh capital investment from the private sector and other sources has increased Zambia’s annual copper production, which rose to above 500,000 tons in 2006 for the first time since 1985.

However, a range of problems has negatively affected Zambia’s performance in the mining sector, including mine accidents, labour disputes and fuel and electricity shortages. Furthermore, serious concerns have been raised regarding the lack of benefits for most citizens, poor corporate social responsibility standards on the part of the new mine owners and appalling health, safety and environmental standards on the mines. Moreover, while privatised mines have recorded large profits, the Zambian government itself has acknowledged that its revenue from copper, as a proportion of government income, has been very low.

So-called tax concessions have contributed to the low revenue being received by government. According to a 2004 World Bank report on taxation, Zambia’s copper-mining industry only contributed around 12% of all corporate tax revenues, while copper exports made up almost 70% of the total export in that year. Civil society engaged in mining has expressed its frustration; they do not see the developmental benefits from the mines they were promised and expected. It seems that the wealth created leaves the country before Zambians can benefit from it, especially when copper prices were reaching record highs in 2007-2008 (up to $9,000 a ton).

For the Zambian people, privatisation has been disappointing. The new mining companies are not obliged to provide social infrastructure such as jobs, schools, hospitals and HIV/AIDS prevention programmes, which were previously the responsibility of ZCCM. It can therefore be argued that little or no economic development has resulted from the privatisation of the mines, although copper production has been high.

There is no doubt that mining operations can have both a positive and negative impact on local economies, as demonstrated above. However, governments have an important regulatory role to play in integrating the mining sector into national development. While economic growth has not been high in Angola and Zambia, this is not necessarily due to their respective ownership models. What distinguishes both is poor governance.

All the same, it can be argued that even if Angola and Zambia had used the same model of mining as Botswana, their economic outcomes would still be much the same as they are today, because of the lack of transparency and accountability in their governance structures. Botswana owes its economic success to its transparent and accountable governance structures, more than its ownership model. And its ownership structure was more a result of rational policy planning, rather than political contestation.

Neil Zitha holds a BA (Hons) in international relations from the University of Venda. He oversees the production of GGA’s annual publication, Africa Survey, and also works as a researcher on GGA’s natural-resource governance and local-governance projects. His research interests are in African political economy, international and intra-African trade, political developments and conflict management in Africa, the promotion of democracy and good governance, foreign and public policy analysis and security studies.[