Welcome to 2025! As I write this column, I am preparing to attend my 12th African Mining Indaba. The theme for 2025 is “Future-Proofing African Mining, Today!” This is built on four pillars, all worth interrogating more fully, but we’ll focus predominantly on the first: “Industrialising Africa”.

This is clearly critical to realising broad-based development on the continent. Industrialisation is the most labour-absorbing pathway through which to generate sustained development, as it creates a middle class. A broad middle class, in turn, builds a wealth base, which sustains a country into the future and helps to consolidate democracy (or even agitate for one, which is why dictators don’t like a middle class). Sovereign wealth funds can also be a useful mechanism by which to achieve this, but that requires robust governance institutions as a precondition to avoid the pot being looted by unaccountable politicians and officials.

Johannesburg, South Africa. Photo by EMMANUEL CROSET / AFP)

Unfortunately, mining prominence in any given African nation has historically not generated industrialisation. South Africa is a rare exception, and arguably only escaped this trap because the combination of diamonds, coal and gold from the late 1800s onwards created a simultaneous demand for finance. This created what scholars have called a minerals-energy-finance complex (MEFC), with a relatively large and robust manufacturing sector, sustained by cheap and reliable electricity.

Even South Africa, though, is likely afflicted by Dutch Disease—the phenomenon whereby a mineral-wealthy country suffers declining manufacturing performance. It works through two complementary mechanisms: First, a mineral or oil-wealthy country’s currency appreciates through exports, undermining the cost-competitiveness of exported products in the tradable sector. Second, the extractive industries attract skills and resources away from the manufacturing sector, further jeopardising its competitiveness.

For the sake of comparison, consider briefly Zambia and Rwanda. Zambia is mineral-wealthy—copper-rich, to be specific. Mineral rents—the difference between the value of production for a stock of minerals at world prices and their total costs of production—have been wildly volatile for Zambia for the last fifty years. For a host of reasons, copper was unable to provide a firm foundation for manufacturing employment growth in Zambia. Employment in industry (as a share of total employment) was at 7.98% in 1991, around when copper prices plummeted. By 2000, that share had dropped to 5.75%. Mineral rents were at a tiny 0.62% of GDP at the time. By 2021, mineral rents had shot up to 28.25% of GDP, nearing the 1974 high. Manufacturing employment share, on the contrary, grew to 12.23% by 2017 but has since declined. While it is true that much of this growth occurred while mineral rents were declining, the graph shifts substantially from 2015, with mineral rents going sky-high while manufacturing employment fell. This correlation doesn’t prove Dutch Disease, of course, but it’s clear that copper production isn’t driving sustained industrialisation, despite it being a “critical mineral” for driving low-carbon energy and transport revolutions.

In Rwanda—if the figures can be believed and we temporarily ignore Kagame’s plunder of the eastern DRC—has grown from a mere 2.35% in 1991 to a high of 17.21% in 2020. That is a full five percentage points higher than Zambia’s peak. Rwanda’s mineral rents have never been higher than 1.06% of GDP.

Rwanda’s multidimensional poverty headcount ratio (% of the population) has declined—on the World Bank’s score—from 58.8% in 2013 to 48.8% in 2019. In Zambia, 66.4% of the population was still living in poverty in 2015, and while this figure dropped to below 50% in 2018, it had climbed back to the 2015 level by 2022.

I’ve seen the benefits firsthand that mining can bring, especially in places like Zambia, and the local-level benefits (and costs, sometimes). However, the national picture often remains grim in countries with high or volatile mineral rents as a portion of GDP.

I do not believe that this is because of mineral extraction per se, but there are things that tend to happen in mineral-wealthy and weakly institutionalised countries that undermine manufacturing competitiveness and complicate potential pathways out of poverty. Governments receiving mineral rents often have very little incentive to build a broad tax base. Even if they did, it turns out that building a viable manufacturing base (to underpin a broader tax base) just because one has good raw ingredients with which to do so, is not as easy as it seems. For instance, just because one has copper doesn’t mean that one should become a solar panel producer.

The 2025 Mining Indaba says it will focus on “developing strong downstream economies through in-country processing & manufacturing.” But this conversation has been going around in circles for as long as I can remember. The truth is that it’s very difficult to build a manufacturing industry without a stable and affordable electricity supply, robust infrastructure, and a clear industrialisation policy based on real global value-chain opportunities instead of wishful thinking.

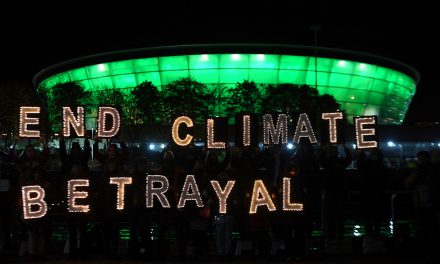

The other three pillars are “future-proofing our communities,” “delivering effective net zero & Just Energy Transition strategies,” and “maximising on (sic) Africa’s critical minerals endowment.” These are all great conversations to be having, but there is an understandable cynicism among many long-term observers that this is well-trampled ground. We all know that mining needs to do better at serving its local communities (without becoming substitutes for service delivery that local government should be responsible for), but there remains too large a divergence between boardroom talk and coal-face practice. Similarly, we talk about net zero while calling coal a “critical mineral.”And, talking of “critical minerals,” we still haven’t really decided what counts in this basket, depending on who exactly these minerals are critical for. If they’re critical for Europe, for instance, because the EU wants to limit its dependence on China, where exactly do we think the incentive for local value-addition will come from?

The bottom line is that unless leaders of African countries step up to the plate, Africa’s minerals (including ‘critical’ ones) are likely to prove a continued curse. A major difficulty is that several minerals critical to the energy revolution (like cobalt) are lootable and moveable. This creates complex dynamics within and between weakly institutionalised countries. Consider the Rwanda/DRC debacle—a subject for my next column—in which the former is likely sponsoring an armed rebel group in the latter, creating destabilising effects. How to prevent that kind of thing needs to be given more serious attention at forums like the Mining Indaba.

Dr Ross Harvey is a natural resource economist and policy analyst, and he has been dealing with governance issues in various forms across this sector since 2007. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town, and his thesis research focused on the political economy of oil and institutional development in Angola and Nigeria. While completing his PhD, Ross worked as a senior researcher on extractive industries and wildlife governance at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), and in May 2019 became an independent conservation consultant. Ross’s task at GGA is to establish a non-renewable natural resources project (extractive industries) to ensure that the industry becomes genuinely sustainable and contributes to Africa achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ross was appointed Director of Research and Programmes at GGA in May 2020.