Introduction

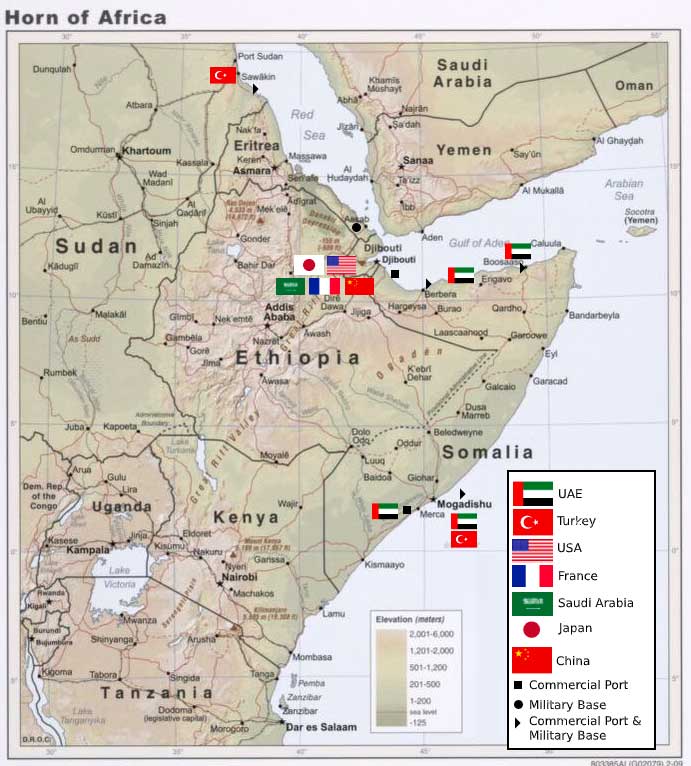

The Horn of Africa is a geographical region falling within the horn-shaped part of North Eastern Africa that protrudes into the Indian Ocean. There has been an arbitrary definition of which countries constitute the Horn of Africa. The ‘principal’ countries of the Horn Region are usually understood to include Uganda, Kenya, South Sudan, Sudan, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia. As it is a political conception of the sub-region, in a more geographic sense, the region is limited to Ethiopia, Somalia, Djibouti and Eritrea.

From a strategic point of view, the region is sometimes called the ‘Greater Horn of Africa’, which stretches southwards to the Great Lakes Region. For the purpose of this paper, the political Horn is the area of focus for the reason that it includes all the countries in the region which are witnessing intense militarization activity. The region is geopolitically strategic for the African and the world economy, security and trade. Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia are located at the entrance of the Red Sea, which is one of the most crowded maritime coasts with several harbours and ports that bridge the Arabian and Indian peninsulas.

The sub-region is an easy outlet for raw materials, oil, and natural gas from Gulf countries to Europe, as well as a way for consumable goods to reach the African market from Europe and Asia. The sub-region is also central for power projection on the African continent, the Red Sea, the western part of the Indian Ocean, and the Arabian Peninsula for actors seizing bases here.[1] Thus, these geographic facts personify the Horn as a strategic location for regional and global actors.

The US ambassador to Djibouti Jonathan Pratt (C) speaks during the Partner Appreciation Day for the Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) to celebrate the 20th anniversary of partnerships among Djibouti and the allies at the US Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti on November 10, 2022. (Photo by AFP)

Militarisation in the Horn of Africa is arguably a result of a post-colonial and post-Cold War inordinate rivalry of global powers to counter one against the other. Global and regional powers that are opening military bases and naval fleets in the Horn of Africa have the aim of countering security threats (terrorism, piracy, and ocean armed robbery), securing trade routes, projecting military and diplomatic capability, and winning friendly regimes in the sub-continent.[2]

Similarly, it is undeniable that host states get economic trickles and reduce the potential for terrorist attacks in exchange for allotting military bases in their territory. The competition of global and regional powers to win friendly regimes may have the potential to undermine host communities aspirations for improving governance, democratisation, and accountability, as was the case in during the Cold War times. Unfortunately, countries in the region do not have a common mechanism to prevent any adverse consequences from the proliferation of foreign military bases in the region.

This paper, therefore, examines the context, trend, implications and possible response mechanisms pertaining to the expansion of foreign military bases in the Horn of Africa.

The regional context of the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa is seen as a complicated security block in the continent, facing interwoven challenges from demographic to economic and from political to security matters. The region’s inhabitants share relatively similar ways of life in terms of religion, political history and mode of economy. They also seem to have had long-lasting mutually destructive tendencies and experiences.

The demographic structure of the region changes rapidly. The youth population in the region has been rapidly increasing, and the average age is below thirty. It is possible to argue that the countries of the Horn of Africa are among the fastest-growing populations in the world.[3] The average population growth rate in the region, except Djibouti (which is less than the average), is above 2%.[4] Youth poverty and unemployment, vulnerability to addiction to substances and epidemics are also the social ills people in the region have been faced with.

Environmental susceptibilities that have made states and societies not able to produce sufficient food and other kinds of physical provisions are the main challenges in the region. The susceptibility of the region, among other things, can be explained by the prevalence of drought and hunger which have profound socioeconomic and political consequences.[5] Impacts of climate change, competition and conflict over natural resources, disputes over transboundary resources (particularly water) and fishery are some of the daunting problems in the region.

The economic structure of the countries in the Horn of Africa is very much skewed in favour of agriculture. Despite their economic dependence on rain-feed agriculture which is vulnerable to the negative impacts of climate change, there are some signs of economic growth in recent years. Sudan, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Eritrea have growth per annum between 5% and 9% of GDP, while South Sudan and Somalia are growing at a slow pace due to continuing conflicts. Focusing only on five of the countries in the region (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan), the African Development Bank reports that the total GDP for the region is approximately US$188 billion, with Sudan (US$95 billion) and Ethiopia (US$72 billion) together accounting for 89% of the total GDP.[6] Despite this, the need for humanitarian assistance aid is beyond imagination. The Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported the need for more than 2.4 billion USD to rescue 32 million people trapped by persistent drought, climate change, and conflict in 2023.[7]

Most states of the Horn of Africa have authoritarian and autocratic governments that suffer from a lack of popular legitimacy, a culture of democracy, human rights protection and observance of the rule of law.[8] In some of these states, such as Somalia, South Sudan, and Eritrea, the institutions lubricating democratization and good governance are either too weak or totally non-existent. Almost all governments and people in this region have inherited the legacies of authoritarian predecessors and found themselves in the circuit of recurrent election-related violence.

A significant number of communities are experiencing and complaining about political and economic exclusion. As a result, there are a number of incidences and several ongoing questions for statehood. South Sudan and Eritrea achieved it in the past 30 years.[9] In Somalia, Puntland’s claim for larger regional autonomy,[10] if not independence, and Somaliland’s claim for independent statehood are still outstanding issues. The Darfur people in Sudan continued their struggle for more than 20 years against what they call political repression by the central government dominated by Northern Arab ethnic groups. Ethiopians were protesting against the political group that took power in 1991 on grounds of domination and monopoly of power and resources by Tigray Peoples Liberation Front (TPLF). Following the fall of the TPLF-dominated regime, the conflict in Ethiopia has taken a different trajectory. Generally, throughout the region, political contestation is overtly moulded around identity politics. Social identity (religious, ethnic, and tribal) has been crystalized and mobilized to challenge their counterpart. Actors in all these cases look for allies and support from regional and global powers.

For many decades, the region has experienced wars between states, secessionist movements, intrastate violent conflicts, foreign interventions, terrorist attacks, piracy and violence after contested elections.[11] In a fashionable manner, most of the incumbent governments in the region were former rebels (Eritrea, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Somalia) in their respective countries, where narrow domestic political space stimulates another round of insurgents. There are also conflicts looming in the Horn of Africa that stem from failed states in the region and countries with unstable transitions. The failure of Somalia and South Sudan, the swinging impasse between Ethiopia and Eritrea, unsettled boundary problems between Eritrea and Djibouti, Ethiopia and Sudan, and the ongoing internal violent conflict within South Sudan, Ethiopia and since recent times Sudan are causing imminent security vulnerability in the region.[12]&[13]

Border conflicts and territorial claims that invited external powers as patrons of a particular state have long dominated the Horn. The region also experienced irredentism and natural resource competition such as water and land producing a new spiral of regional insecurities with implications for secured livelihoods and economic viability.[14] The region’s individual states have inherited the legacy of sponsoring insurgents against one another. During the Cold War period Somalia, Ethiopia and Sudan did it which facilitated the secession of large territories from each country; Eritrea from Ethiopia, South Sudan from Sudan and Somaliland (though in the formative stage) from Somalia. In the contemporary period, the new states (Eritrea and South Sudan) did the same to their neighbours by providing military aid and access to bases for military activities.[15]

The region also has emerged to be a major front in the war on terror that became a defining feature of global powers’ strategic agenda after the 9/11 attacks in the United States. The region’s proximity to the Middle East, particularly Yemen, where al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula established its base, made the region a staging ground for undertaking counterterrorism operations across the sea. Terrorist organizations growingly considered the region as safe haven in the ruins of some Horn of Africa states like Somalia.

Trends in the Expansion of Foreign Military Bases

France has had military bases and garrisons in Djibouti (Chabelley Airfield, Lemonier, and Ambouli) since its protectorate rule (1883–1887). The French Force in Djibouti (FFDj) has a wide range of operations both on land and in the sea of the Horn. Similarly, the UK has military bases in Kenya and Somalia, inherited from colonial times. Despite declining French military participation in Djibouti, the mandate and strength of French military bases have been enhanced since the 2011 defence cooperation treaty.[16]

Albeit France’s and the USA’s existence in the coastal line of the region for a long period of time, the influx of foreign military bases and naval activities boomed after China’s military base establishment in Djibouti in 2008. Since then, the edges of Bab-el-Mandeb have attracted foreign military intrusion from the world powers to the regional powers, which has crowded the coastal strips with military airfields, military logistic centres and facilities, a war fleet, military training sites, and ocean patrols. Global and regional powers vying with each other advanced even into the hinterland of the Horn of Africa (for example USA established military bases in South Sudan and Uganda) in search of military bases at an accelerating rate.

Fig 1: Geographical location of the Horn of Africa (Source: MENAF.com)

For the last two decades, it is believed that military base establishment and military fleet proliferation around the coastal line of the Horn have been stimulated by three major historical events. Among these, the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the USA and the subsequent global war on terror is the major one. The second factor is the proliferation of Somalia-based piracy and armed robbery that jeopardized the security of trade vessels passing through the Red Sea and Babel-el-Mendel. The third phenomenon is the rise of China in the global power arrangement and its associated move in establishing military bases and trade port development in Djibouti since 2008.[17]

The USA established its first permanent military base in Djibouti, actually in Africa too, in 2001 at Camp Lemonnier[18] handed over by the French, then in Arbaminch, Ethiopia (2003)[19], and Kismayo, Somalia (2007). In 2002, the USA invited 33 of its ally states to participate in naval operations against terrorism and piracy[20]. NATO was active in the region from 2009–2016 under ‘Operation Ocean Shield’, supporting the government of Somalia in military training to combat piracy and violent extremism[21]. This paved the way for many countries like Spain, Germany, South Korea, and Italy to join the game. In 2007, the USA expanded its military bases in Djibouti from 39 to 500 hectares of land[22] to consolidate its military existence in the region and host the UK military facility in its military bases, as France did for Germany and Spain[23]. Indeed, the UK has more military bases in the Horn of Africa; Somalia and Kenya with active involvement in countering terrorism against Al-Shebab in the region.

The consolidation of US military power and its allies in the Indian Ocean and the coastal line of the Horn may motivate China to join the race. While China established its first overseas military base in 2008 by leasing 36 hectares of land in Djibouti, it was dubbed as a logistics hub for the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN)[24]. However, China has been involved in military facility installation and expansion since 2013 for purposes like rescuing Chinese citizens in times of crisis, executing its international commitment to peacekeeping in Africa, delivering humanitarian aid for Africa and West Asia, and boosting Chinese economic contribution to Africa like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) project.

China’s strong presence in the region further intensified the race for owning military bases among global and regional powers. France joined the EU mission for anti-piracy in 2008, signed the defence treaty with Djibouti in 2011, and established an advanced operation base in 2014. Similarly, Germany and Spain joined the party in 2008[25] to participate in the Atlanta operations, which are designated as global power institutions by the EU.

Japan and Italy arrived at Ambouli International Airport, Djibouti, next to their Western allies in 2009 and 2013, respectively[26], to establish logistics bases for their naval activities. Japan expanded the mandate of the military base in Djibouti in 2018 to include carrying out military cooperation with the Horn states and with India’s naval activities in the Northern and Southern Indian Ocean. India also agreed with Japan to use the military base in Djibouti and also leased an Island from Seychelles for installing military bases in order to compete with China on the Indian Ocean and coastal lines.

Likewise, Russia’s Navy exists in the Horn of Africa, parking in Djibouti ports on a non-permanent mission. Russia secured a military base in Eritrea in 2018.[27] Russia is scouting military bases in the region, and Somaliland and Sudan are the leading candidates after Djibouti’s rejection of renting a permanent military base for Russia in fear of clashes with the USA and its allies.

Similar to the above-mentioned strong presence of global powers, regional powers have also come to the Horn of Africa with similar intent. Iran had established a naval base in Assab, Eritrea, in 2008 in the name of protecting the oil refinery site. However, due to the civil war in Yemen, in later years Eritrea and Iran found themselves in a confrontational relationship. Iran supports Houthi rebels, and Eritrea lines up with Saudi Arabia. As a result, in 2015, Iran left Assab, and Saudi Arabia stepped in under the gist of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Likewise, as a regional power in the Middle East, the oil-rich UAE became involved in military base establishment and commercial port development, first with its short-lived attempt in Djibouti, Somalia (Mogadishu), and finally in Berbera, Somaliland.[28]

Another Middle East political gladiator, Israel, also established military intelligence bases in Massawa, Ambba Sawara, and Dahlak in Eritrea, to watch and monitor Iran’s movement. Simultaneously, Egypt also sent a military boat from Port Safaga in 2017 to support its allies in the Yemen civil war and block Iranian vessels from reaching the ports of Yemen. Turkey also established military bases in 2009 and built its largest overseas military facility in Mogadishu in 2017.[29] In the military bases, Turkey trained Somali military personnel and patrolled the ocean to counter piracy. Turkey has also military bases in Sawakin, Sudan, which helps to project its diplomatic power in the region and to counter Egypt’s involvement in Libya.[30]

Foreign military base establishment in the Horn of Africa caused political hostility and rivalry between Middle East regional powers. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE stood against Iran, Turkey, and Qatar. The Western powers support the former group, while Russia backs the latter. These competitions provoked Egypt to send troops to Assab, Eritrea, in fear of conflict over the Hala’ib Triangle, the contested territory between Sudan and Egypt, while Sudan signed the Sawakin agreement with Turkey to counterbalance the Egyptians move.[31] Saudi Arabia convinced Issaias Afeworki to drive back Iran from Assab and replace it with the GCC agreement. Saudi Arabia has also been successful in blocking Iran’s relations with Djibouti and Sudan. Saudi Arabia is winning alliances displacing not only Iran but also Qatar. The policy of the Saudis and their position in the Yemen civil war helped them to beat their main Middle East rival, Iran.

Implications of the Expansion of Foreign Military Bases

The proliferation of foreign military bases in the Horn of Africa has various implications for countries in the region. The trends and new developments in this regard may avail opportunities for host states in the region that could help them fulfil their strategic and short-term national interests. Obviously, this requires prudent policy and skilful diplomacy. On the other hand, the expansion of foreign military bases in the Horn of Africa could also be a source of concern for countries in the region. In light of these, the opportunities and challenges associated with the expansion of foreign military bases in the region are discussed hereunder.

To begin from the positive side, the expansion of foreign military bases in the Horn of Africa has brought undeniable economic benefits to the host states through leasing military bases, harbours, and airfields. Djibouti alone leased military bases for more than 6 foreign powers, which helped the country to collect more than 300 million USD per year.[32] Sudan, Eritrea, Somalia, Somaliland, and Puntland generate a sizeable amount of hard currency from leasing military bases and harbours.

Since countries like UAE, China, Japan and Turkey are involved in port development, this has led to an increase in low-cost, modern, and accessible port service for the Horn countries. As a result, the volume of trade increased from time to time. Influential multinational corporations from the UAE, Saudi Arabia, China, Turkey, and Japan drain a large amount of foreign direct investment and port infrastructure development.[33] The coastal countries of the Horn of Africa are showered with chequebook diplomacy. The oil-producing Gulf States are also depositing, lending, and donating huge dollar reserves for the host countries. This is a blessing for those poor states suffering from a shortage of hard currency.

The Horn states also benefit from support in diplomacy, military technology, training, military infrastructure and facility development through military cooperation and border security protection. The Horn of African states used foreign military bases as a weapon to check the influence of superpowers through their own rivalries. For example, Somalia countered the UAE by approaching Turkey and Russia. Eritrea suspended the deal of the Assab port for Iran by replacing Saudi Arabia.

The arrival of foreign militaries has also helped protect coastal trade lines from piracy and armed ocean robbery. It also protects the region from terrorist attacks. Most of the foreign military missions in the sub-region were to counter piracy, terrorism and attempts to block the Red Sea’s shipping path. In tune with this, the Horn states were able to enhance the capability of their navies, and countries like Ethiopia are trying to revive their navies after three decades.

On the other hand, however, foreign military base expansion has enormous adverse effects on the region. Among these adverse effects, mention can be made of the possibility of proxy wars among rival regional and global powers, discorded relations between domestic political forces, the tendency of political patron-clientelism, allowing the legacy of colonial domination to continue and impeding democratization and the will of the general public.

Foreign powers want to override the host countries’ strategic policy goals. The foreign powers negotiate to advance their interest by weaponizing humanitarian aid, military cooperation, development assistance and technical support. Host states may reverse their strategic policy goal to show their loyalty to the powerful states. Regional powers such as Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Qatar, overtly influence host states in their favour. Perhaps, the UAE’s confrontational relation with Djibouti and Somalia is a good showcase of foreign powers and host states strategic policy differences. During the Gulf crisis, the UAE asked Somalia to join the political blockade against Qatar despite Somalia’s policy of neutrality. In Djibouti, UAE’s Port management made the facility underutilized despite Djibouti’s interest in large-scale operation. UAE and Saudi Arabia openly support Somaliland and Puntland political actors’ interest to punish Mogadishu for its disobedience. Indeed, Somalia and Djibouti suspended the operation of the UAE in their country. But, what would happen if it was a certain superpower instead?

An unstoppable race for military bases and harbours may have the risk of military clashes among rival powers. The signal was observed when the US accused China of hurting military activities in the region in 2008.[34] The current security crisis in Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia is further complicated by the world’s powers’ competition for winning client regimes in these countries. Similarly, regional powers’ presence in coastal areas and berths with competing interests may trigger the same incidence. The competition between rival Gulf States over winning military bases in host countries is good evidence for this.

Moreover, a swinging pattern of alliances with local, regional and global powers is seen following the beginning of the Yemen civil war and other global situations such as the Gulf Crisis. Such unstable and volatile relation affects the region’s sustainable peace and security. In recent years, for instance, Eritrea shifted sides from Iran to Saudi; Mogadishu from UAE to Turkey; Djibouti denied bases for Russia; Sudan sides with Ethiopia for some time and with Egypt other times owing to the dispute over the Nile water and Ethiopia’s Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Such rapidly changing alliances associated with foreign military bases’ proliferation breed instability in the region.

It is also being observed that the proliferation of foreign military bases impairs the territorial integrity and stability of individual countries in the Horn. Global and regional powers that fail to win friendly regimes have a tendency to trigger instability to bring regime change and upset the status quo. Egypt, Iran and Russia showed signs of involvement in turbulent situations in the Horn of Africa’s individual state’s instability. The UAE showed support for Somaliland and Puntland so as to be able to invest in Bossasso and Berbera in response to Somalia’s measure to deny it access to similar facilities in Mogadishu.

Most foreign powers are also fuelling discord among host states’ political actors by influencing them to stand against the interests of their rivals. Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Somalia are freaked out by their allies. Once, Djibouti and Somalia agreed to prevent the UAE from instigating conflict between the two states.[35] When Sudan agreed to give a military base to Turkey in Sawakin in 2017, Egypt was irritated fearing the flare-up of conflict on the contested territory and sent troops to Assab to be stationed in the Saudi military base.

Foreign military base proliferation allows the legacy of colonialism to continue and keep colony-coloniser relations. Most of the time, the superpowers have more military bases and influences in their former colonies. For example, France has a bigger influence in Djibouti and Britain in Kenya and in former British Somalia. This may pave the way to continue the superpowers’ colonial time interests through other means in the region.

The crowded condition of foreign military bases in the region has an effect of militarization where regimes tend to increase the role of military and security institutions in political, economic and social spheres. Foreign patrons support authoritarian clients and halt social change by militating against political developments that would bring an accountable and responsible regime which will substantially dwarf democracy at the local level. Such conditions make the local political development trajectory stagnant, if not worse. Authoritarians’ military solution in the region, in turn, intensifies ethnic tension, legitimacy crisis, strained state-society relations and causes a reverse in democratisation. As a result, ruling elites cling to power through patronage of the superpowers.

The expansion of foreign military bases is also associated with illegal armed trade and the militarization of host states and civilians. Actors supply arms and military technology in unstable states of the Horn to combatants found in their policy favour. This may permanently sustain and perpetuate violent conflict, which is a bad signal for Africa’s peace, development, and security aspirations. The New Times reported that the Eastern Africa Standby Force (EASF) raised concern over the involvement of external forces in the region which has the potential to smash the effort of building sustainable peace and stability.[36]

The Need for Coordinated Response

Though the adverse effects of the proliferation of foreign military bases pose a threat to the Horn states’ sustainable peace, no significant measure has been taken by countries in the region and their regional organizations such as IGAD to mitigate it. Due measures need to be taken by individual countries, regional organizations and foreign powers.

It is believed that strong institutions can protect the sovereignty of a particular state and serve citizens’ interests. Despite this dictum, the Horn of Africa is characterised by conditions of state failure and institutional collapse in many instances. This clearly put them in a weaker position in bargaining with foreign powers. Therefore, the first thing the Horn of Africa states need to work out is decreasing internal vulnerability by easing tension among domestic political actors through political inclusion and reconciliation. Individual states should improve their institutional capacities to the level that could serve diverse political interests and aspirations. It is only in this way that individual states could consolidate improved governance with the potential to protect the interest of citizens in both domestic and international affairs.

The Horn of Africa individual states also need to promote regional cooperation around shared objectives and against common threats. Regional institutions such as IGAD must initiate trade, political, military and security cooperation in the region to give African solutions to its outstanding problems. Recently, Kenya and Ethiopia have advocated market and economic integration of the Horn states to increase the region’s self-reliance. States in the region have to diversify sources of regional and global funding to minimize the traditional dependence and the resulting influence.

Moreover, regional institutions like IGAD have to mobilize member states to tackle the adverse effects of the proliferation of foreign military bases. In this regard, IGAD may serve as the platform for cooperation on information sharing, avoiding destructive competition and security concerns about foreign military bases in the region. Though mistrust among member states appears to be pervasive, it is advisable to avoid duplication of effort, design a flexible mitigation plan and act cooperatively at least on important common priority areas. To this effect, states in the region and their regional organizations (IGAD and AU) may draft and ratify protocols about foreign military bases aiming at averting military confrontation, reducing foreign power interference in the countries’ domestic affairs, monitoring the movement of weapons to and from the foreign military bases, protecting the states sovereignty and territorial integrity as well as encouraging foreign powers positive engagement in the region.

The Horn region needs an open discussion with global and regional powers on the agenda of reducing the number of military personnel and military facilities to relieve the suffocated harbours, airfields, and military camps through individually and regionally feasible and internationally acceptable initiatives. Simultaneously, the UN, AU, Arab League, IGAD and other regional organizations need to work out how to empower local states to ensure the security of the coastal lines. It is also good to develop a mechanism whereby countries having military bases in the region commit themselves to assisting host states in building institutions, maintaining neutrality in regional matters, and contributing to knowledge and technology transfer so that in the end the latter take over the task of securing the Red Sea and Indian Ocean in the long run.

Conclusion

The Horn of Africa is a geographically significant region falling within the horn-shaped part of Northeastern Africa including Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Kenya and Uganda. The region’s geo-political and strategic importance increased more than ever in history due to the proliferation of piracy, terrorism, internal instability in the member states and global and regional powers competition. Political, security and economic vulnerability of the sub-region made the establishment of foreign military bases an easy-go business.

Countries such as Djibouti host multiple military bases and airfields. The military base establishment is more transactional (lease money, aid, loan, development assistance, Foreign Directed Investment) for their own short-term and long-term interest. Western powers (USA, France, UK, and Germany) and their allies (Japan, South Korea, Italy, Spain), as well as China, Russia, the Gulf States (Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar) and the Middle Eastern states (Turkey, Egypt, Iran and Israel), have joined the race for military bases in the Horn of Africa region with rival strategic goals.

Though the existence of foreign military bases in the region may have economic trickles and security-related gains to the host states, it also adversely affects national sovereignty, instigates instability as well as increases militarisation of society, fuels armed clashes between rival powers and shores up authoritarian client regimes by suppressing the people’s demand for accountable and responsible elected government.

In minimizing the adverse effect of militarisation in the Horn of Africa, states in the region should expand and strengthen trade, security and financial cooperation to decrease heavy reliance on foreign powers. Individual states and regional organizations such as IGAD and AU should also initiate multilateral mechanisms to monitor and manage military engagement in the region. It appears wise to think about putting in place a system of hosting foreign military bases that prioritises sustainable institutional building rather than chequebook diplomacy to escape the trap of power projection and foreign influence on the countries’ strategic policy.

Notes

[1] Rondos, A. (2016). The Horn of Africa Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development, (6), 150–161.

[2] Melvin, N. (2019). The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region; SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security no. 2019/2, Apr. 2019.

[3] Stanislas, P., and Iyah, I. (2016). Changing religious influences, young people, crime, and extremism in Nigeria Religion, Faith, and Crime: Theories, Identities, and Issues, 325–345.

[4] African Countries by population number (2023).

[5] African Development Bank Group. 2018. ‘Investing in Transition States: The Horn of Africa Opportunity.’ Investing in Transition States- The Horn of Africa Opportunity

[6] African Development Bank Group. 2018. ‘Investing in Transition States: The Horn of Africa Opportunity.’

[7] OCHA (May 24, 2023) press release, New York

[8] John Markakis (2021). Crisis of the state in the Horn of Africa, Max Plank Research Library.

[9] Bantayehu Shiferaw (2019). State Failure and Nature of State Formation in the Horn of Africa, Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, Vol.21, No. 2, California University Press, Pennsylvania.

[10] Hoehne M, V. (2015). Between Somaliland and Puntland: Marginalization, Militarization and conflicting political Vision, Rift valley Institute. https://pure.mpg.de/rest/item/item_2417357/component/file_2417356/content

[11] Witt A. (2014) 10th FES Annual Conference: Peace and Security in the Horn of Africa “Consolidating Regional Cooperation While Protecting National Security Interests: Diametric Opposition or Precondition for Peace and Security?” Nairobi, Kenya.

[12] Khadiagala GM, (2008). Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility. Africa Program Working Paper Series, International Peace Institute Retrieved from

[13] Turton, D (2006). Ethnic Federalism: The Ethiopian Experience. http://www.ethiopiantreassures.co.uk/pages/derg.htm

[14] Tetra Tech ARD, (2012). East Africa Regional Conflict and Instability Assessment: Final Report. Retrieved from:

[15] Telci, I. N. (2022). The Horn of Africa as a Venue for Regional Competition: Motivations, Instruments, and Relationship Patterns Insight on Africa, 14(1), 73–87.

[16] Gashaw A., and Zelalem M., (2016) The Advent of Competing Foreign Powers in the Geostrategic Horn of Africa: analysis of Opportunity and Security Risk for Ethiopia. International Relations, 4(12), pp.787-800.

[17] Hoehne M, V. (2015). Between Somaliland and Puntland: Marginalization, Militarization and conflicting political Vision, Rift valley Institute.

[18] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=waUVHmQYtus

[19] Kubo, N. (2016). ‘Japan to expand Djibouti military base to counter Chinese influence’, Reuters,13 Oct. 2016.

[20] Melvin, N. (2019). The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region; SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security no. 2019/2, Apr. 2019.

[21] Hoehne M, V. (2015). Between Somaliland and Puntland: Marginalization, Militarization and conflicting political Vision, Rift valley Institute.

[22] Moore, A., & Walker, J. (2016). Tracing the US military’s presence in Africa. Geopolitics, 21(3), 686-716.

[23] Ezeh, K. D., & Ezirim, G. E. (2023). Foreign Military Bases (FMBs) and Economic Security in Africa: Overview of FMBs in Djibouti International Journal of Geopolitics and Governance, 2(1), 10-26. https://doi.org/10.37284/ijgg.2.1.1214

[24] Witt A. (2014) 10th FES Annual Conference: Peace and Security in the Horn of Africa “Consolidating Regional Cooperation While Protecting National Security Interests: Diametric Opposition or Precondition for Peace and Security?” Nairobi, Kenya.

[25] Melvin, N. (2019). The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region; SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security no. 2019/2, Apr. 2019.

[26] Kubo, N. (2016). ‘Japan to expand Djibouti military base to counter Chinese influence’, Reuters,13 Oct. 2016.

[27] Tesfaye, G. (2021). Foreign Military Bases in the Horn of Africa and their Implications to Ethiopia’s National Security (2002-2019), MA Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

[28] Ismail N. Telci (2018). A Lost Love between the Horn of Africa and UAE, Aljeezira, may 28, 2018. Deputy Director of the Middle East Institute (ORMER) and Assistant Professor at the Department of International Relations at Sakarya University.

[29] Hoehne M, V. (2015). Between Somaliland and Puntland: Marginalization, Militarization and conflicting political Vision, Rift valley Institute.

[30] Bantayehu Shiferaw (2019). State Failure and Nature of State Formation in the Horn of Africa, Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, Vol.21, No. 2, California University Press, Pennsylvania.

[31] Tesfaye, G. (2021). Foreign Military Bases in the Horn of Africa and their Implications to Ethiopia’s National Security (2002-2019), MA Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

[32] Ndubuisi Christian Ani (2019). Implication of foreign military bases on the Horn of Africa stability. Tana Forum, May, 24, 2019.

[33] Ezeh, K. D., & Ezirim, G. E. (2023). Foreign Military Bases (FMBs) and Economic Security in Africa: Overview of FMBs in Djibouti International Journal of Geopolitics and Governance, 2(1), 10-26.

[34] Witt A. (2014) 10th FES Annual Conference: Peace and Security in the Horn of Africa “Consolidating Regional Cooperation While Protecting National Security Interests: Diametric Opposition or Precondition for Peace and Security?” Nairobi, Kenya.

[35] Ismail N. Telci (2018). A Lost Love between the Horn of Africa and UAE, Aljeezira, may 28, 2018. Deputy Director of the Middle East Institute (ORMER) and Assistant Professor at the Department of International Relations at Sakarya University.

[36] Julius Bizimungu, (2018). AU military chiefs raised red Flag on Foreign Military Base, July 27/2018, The New Times.