South Africa’s constitution identifies accountability as one of the founding provisions of our democratic system. The link is intuitive, and it lies at the heart of any social contract between citizens and their government. In a democracy, we expect that citizens can and will hold their elected representatives to account. In turn, we expect that representatives are responsive to the concerns of citizens.

Today, South Africa is facing a crisis of accountability. Confidence in our democracy and its core institutions is rapidly eroding.

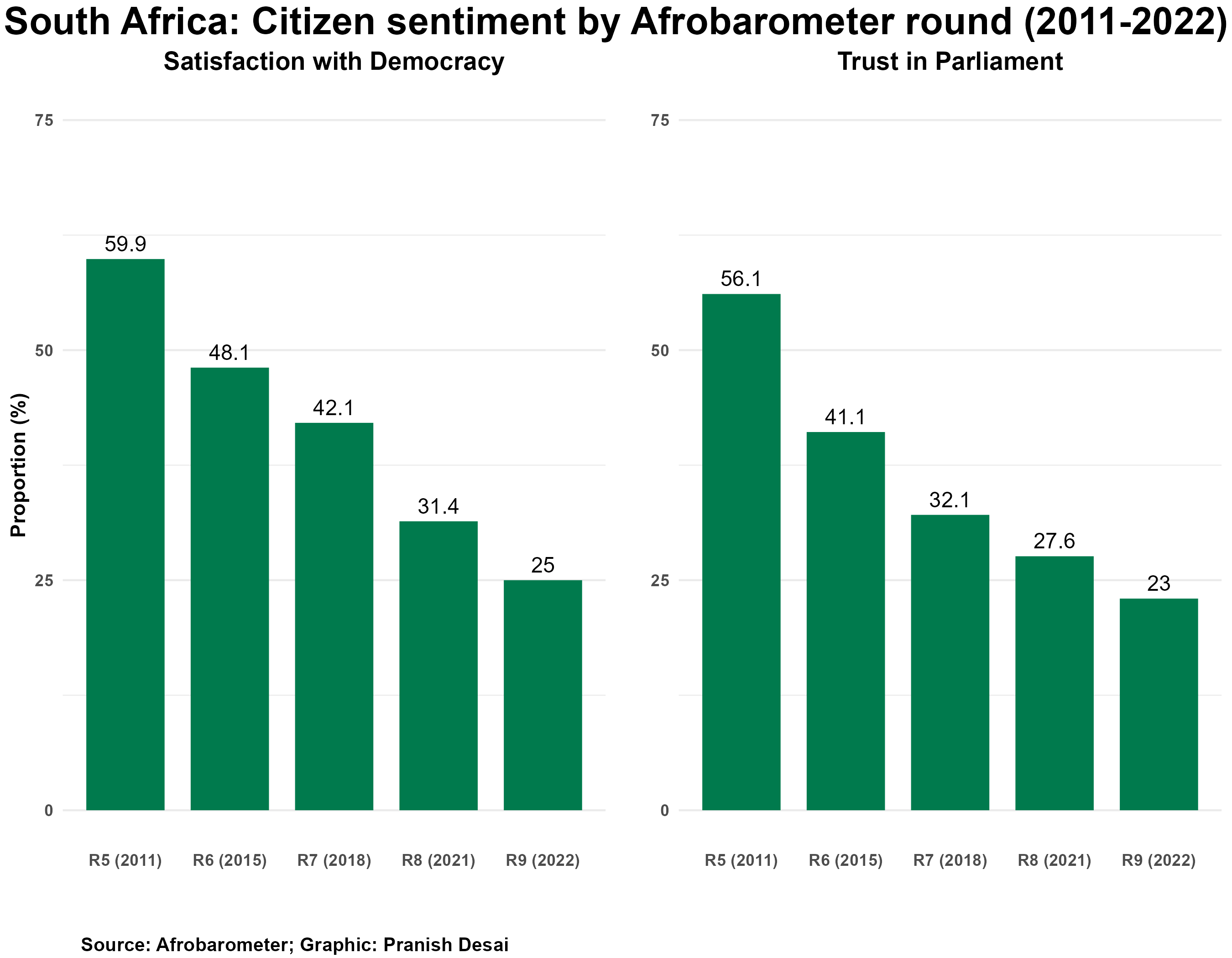

According to a recent Afrobarometer survey, only one in four South Africans expressed satisfaction with our democracy. Less than one in four said that they trusted parliament. A key reason why this is concerning is that parliament is envisaged by the constitution as the main institution that would constrain and prevent the abuse of power by the executive. As the graphic shows, this discontent has become more common over the last decade and is widespread across demographic groups.

In a recent Good Governance Africa (GGA) policy briefing, we tackled the question of how to enhance political accountability in South Africa. The briefing focuses on the related issues of electoral reform and coalition governance.

Our electoral system and coalitions

One reason for the emergence of coalition governments across South Africa is that our electoral system is based on the principle of proportionality. According to our constitution, representation in the national assembly, provincial legislatures and municipal councils should be in proportion to the vote share which political parties receive in elections.

Coalitions emerge in proportional systems largely because these systems produce more political parties over time. As a result, individual parties often struggle to attain the outright majorities needed to govern alone. In South Africa’s case, the ANC’s receding popularity and internal factionalism have strengthened this trend typically produced by proportional electoral systems. Every new political party recently established, and nascent coalition government at local level, constitutes a case in point.

Our electoral framework emerged from our negotiated transition to democracy. Negotiators thought that proportionality could offer inclusive representation capable of reconciling our racial, regional and gender-based divisions. Notwithstanding the overall commitment to proportionality, there are important differences between our electoral system at the local level, and the framework at the national and provincial levels.

At the municipal level, citizens vote for directly elected ward councillors through a constituency system in one ballot while also voting for specific political parties on a separate ballot. Post-election, the second ballot is distributed to ensure overall proportionality. Each method accounts for half of all seat allocation within municipal councils. At the national and provincial levels, there are effectively no directly elected representatives, with political parties deciding which specific individuals occupy legislative seats through election lists.

The problem

Over three decades, this has led to a situation where many voters feel unable to directly apply pressure on national and provincial representatives outside of elections. Many citizens also sense representatives are more accountable to party leaders than them.

While parliament has never pursued introducing directly elected representatives to our national and provincial legislatures, the question of how we can better adapt our electoral system to deepen accountability is as old as our democracy itself.

As one recent commentary notes, no less a figure than former President Mandela foresaw the problems which a complete lack of directly elected MPs could cause for a democracy marred by stark inequalities. The issue was officially considered by a cabinet-appointed commission in 2002, and as part of two parliamentary convened assessments in 2011 and 2017 respectively.

When the Constitutional Court struck down the previous electoral act in June 2020, it added a new component to the discussion by mandating parliament to revise our electoral system in time for the 2024 general elections. Although the crux of the court’s directive was for parliament to introduce a means for independent candidates to stand for national and provincial legislative seats, it is the related question of whether to introduce directly elected representatives which is most salient.

Several members of the advisory committee, which was established to advise the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) following the court’s ruling, advocated that the most practical way to allow independent candidates to fairly stand in elections is through the introduction of a constituency element within our system. Thus, the committee’s majority recommendation was to adapt a version of our local election system to the national and provincial levels.

In revising our system for the 2024 elections, parliament and the DHA opted for a limited approach by enabling independent candidates to stand, while leaving the system whereby parties entirely determine their own nomination lists intact. As such, even if it withstands ongoing legal challenges, the Electoral Amendment Act ensures that our seventh democratic parliament will still have very few, if any, directly accountable MPs.

Similarly, the impending coalitions era requires reform from other aspects of our political system to ensure effective and accountable governance. The crises currently engulfing many coalition-governed municipal councils threaten the delivery of essential services like water, sanitation, and electricity. Coalition governance does not have to lead to this.

Several coalition-governed municipal councils performed well in GGA’s 2019 and 2021 Government Performance Indexes. One reason is that many of those municipalities respected a fundamental divide between political decision-making and administering municipal responsibilities by independent public servants.

As one might expect, municipal instability has a particularly severe effect on the millions of poor households who rely on municipalities to provide free basic services. Every major political party contributes to this by incessantly bringing forward motions of no confidence, usually on trivial grounds.

This poses a major risk to our political system, especially if parties replicate destabilising behaviour at the provincial and national levels. It would worsen the already untenable situation where only a quarter of citizens are satisfied with our democracy. If left unaddressed, citizen disenchantment will result in voters displaying ever more interest in figures and movements which disregard democracy itself.

So, to preserve our political system, we need to reform it to improve accountability.

The way forward

GGA’s policy briefing outlined several reforms which can fulfil this objective. Many of the proposals we considered already exist, but we evaluated them with specific attention to whether they could deepen political accountability in South Africa.

Regarding coalition stabilisation, the government has indicated that it intends to have a framework in place before the 2026 local elections. To foster accountability, we believe this legislation should centre on requiring published coalition agreements.

Political parties must also display greater maturity in how they grapple with coalition governance. The introduction of a framework will prove less effective if parties keep “fighting over the spoils” while service delivery and financial administration suffer. These basic governance functions should continue even when political instability occurs. This underscores why the government must show greater urgency in implementing existing plans for professionalising the civil service, especially at the local level.

The coalitions era reveals the importance of legitimacy for our democracy. So, the way we elect members of parliament and members of provincial legislatures should also change to allow for direct accountability. GGA favours having half of all parliamentary and provincial legislative seats directly elected through single-member constituencies, with the other half distributed to ensure proportionality.

This will allow citizens to meaningfully pressurise political parties and elected representatives at all levels of government outside of election cycles, an essential characteristic of enduring democracies. The Zondo Commission has also suggested that direct accountability could function as a strong deterrent against political corruption.

Many of the recommendations GGA provides can only realistically be implemented after the 2024 election. However, it is important that policymakers begin laying the groundwork for these reforms so that the seventh democratic parliament can address our accountability crisis with haste.

As a first step towards ensuring political parties and our governance institutions pursue these reforms, civil society organisations, and especially citizens themselves, must be willing to hold parties accountable. For a reformed political system to be seen as legitimate, public consultation processes must be as extensive and inclusive as possible.

Implementing these reforms will be time-consuming and resource-intensive, but they are necessary if we want to realise our constitution’s aspiration for accountability. They are also crucial for strengthening our social contract and preserving South Africa’s constitutional democracy.

A version of this article also appears in the Mail & Guardian