After a decade of improvement in the quality of governance since 2012, Africa is back in the trenches, according to the 2022 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) published in February this year. This time the decline in the standard of governance is attributed to high-risk security situations and widespread democracy backsliding in the continent – including the deterioration of the rule of law and participation, rights and inclusion.

In particular, and in a few African countries, the report reveals that differences in religion, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation, disability, and economic status are used to exclude and marginalise people.

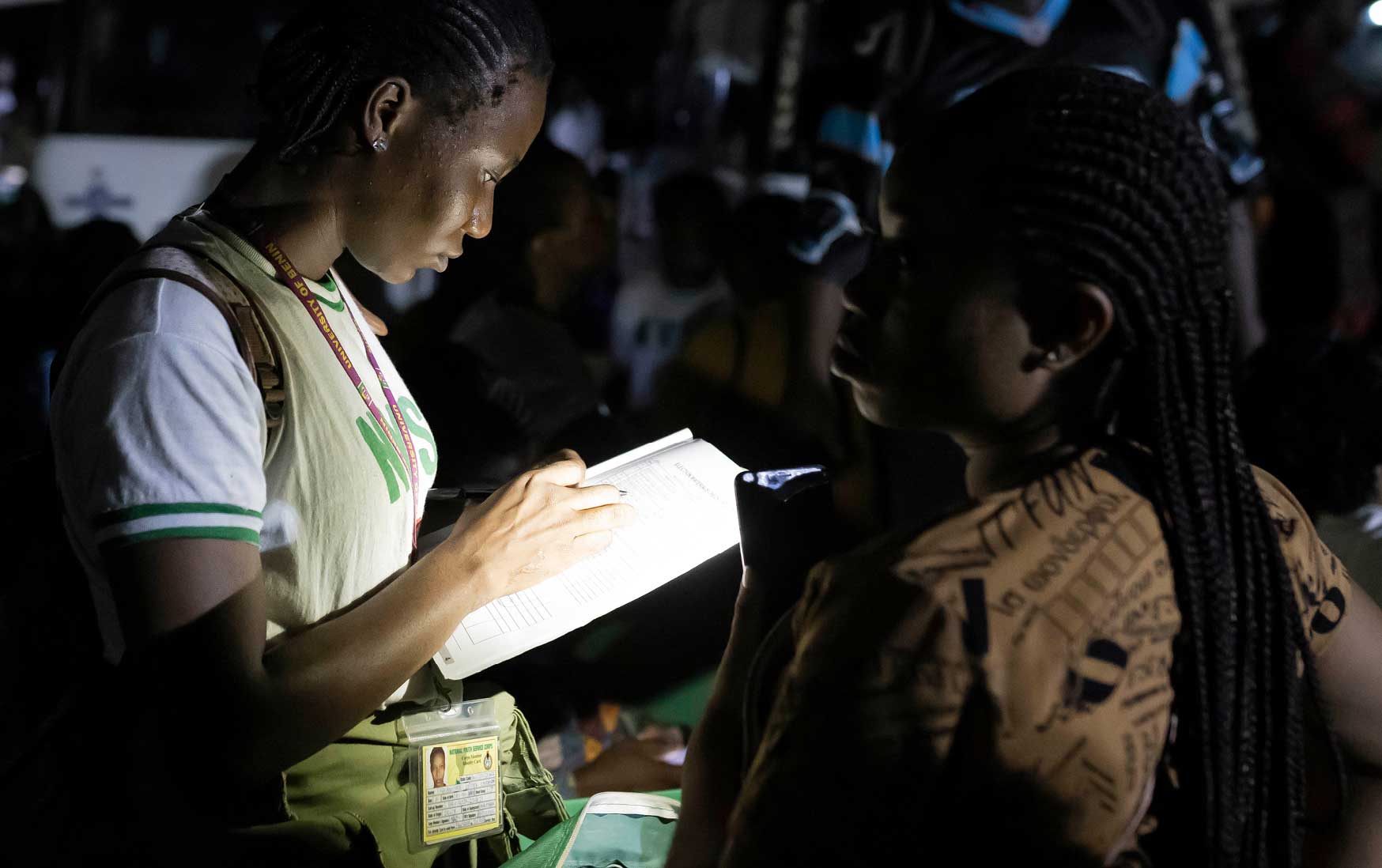

A member of Nigeria’s National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) checks electoral materials in Amawbia, Awka, in February 2023, during the country’s presidential and general election. (Photo: Patrick Meinhardt/AFP)

The continent thus urgently needs to reflect and act to halt this unfortunate trend and get Africa back on the path of human development and economic opportunities. More must be done to promote inclusive governance that goes beyond mere recognition of all the groups in the state; ensuring representation and meaningful participation in decision-making. Inclusive government processes allow civil society and the wider public to be involved in policymaking, regulation and service delivery.

Mo Ibrahim, founder and chair of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, cautions that without a renewed commitment to strengthening governance, Africa might lose all the progress it has achieved.

Ibrahim said at the launch of the Index report: “Our continent is uniquely exposed to the converging impacts of climate change, more recently Covid-19, and now the indirect impact of [the] Russia-Ukraine war … governments must address all at once the ongoing lack of prospects for our growing youth, worsening food insecurity, lack of access to energy for almost half the continent’s population, a heavier debt burden, growing domestic unrest … coups are back, and democratic backsliding spreading. Unless we quickly address this concerning trend, the years of progress we have witnessed could be lost, and Africa will be unable to reach in due time the sustainable development goals or Agenda 2063.”

The report notes that security, the rule of law and human rights have deteriorated in more than 30 out of 54 African countries. Despite this, however, it has been established, in different ways, that governance in Africa has progressed, with 35 out of 54 countries improving overall since 2012.

Underpinning the renewed focus on inclusive governance is the realisation that it contributes to social and economic progress.

The former chief executive officer of the African Union Development Agency’s New Partnership for Africa’s Development (Nepad), Dr Ibrahim Mayaki, speaking to the United Nations at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in November 2020, said inclusive governance is critical to Africa’s development.

“Much-needed reforms on the continent must be guided by governance that is more open to local communities, to civil society and to the private sector,” said Mayaki.

Similarly, the Dutch Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Liesje Schreinemacher, remarked last year at a consultation with African ambassadors on the Netherlands-Africa strategy, inclusive and good governance are essential for Africa’s social and economic development.

“Africans are working hard to reduce their dependence on world markets … likewise, many African countries are making significant advances when it comes to lifting people out of poverty … and yet, given the scale and urgency of the challenge, collective engagement remains necessary … to create the right conditions for development. This includes policy coherence, governance and the rule of law,” said Schreinemacher.

Echoing Schleiermacher’s comments, Antoinette Sayeh, Deputy Managing Director, International Monetary Fund (IMF), speaking at the High-Level Conference on Promotion of Good Governance and Fight Against Corruption, organised jointly with the African Union Commission last year, said Africa’s leaders are stepping up to this challenge – with some ranking even higher than many other emerging markets and advanced economies around governance.

LEFT: Traders on tricycles cross the border between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo at the Petite Barrière border post in Goma in November 2022. TOP: The main entrance to the Sir Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke Market for fish, vegetables, fruits and spices, in Victoria on Mahe island, Seychelles. The idyllic tourist destination is in a tug-of-war over how to keep the economy growing, while protecting its fragile ecosystem. BOTTOM: A member of the Botswana cabinet holds a 1,174-carat diamond discovered in Botswana in June 2021. (Photos: Monirul Bhuiyan, Nipah Dennis, Alexis Huguet/AFP)

“Improving governance and accountability in Africa is not only possible, but it is actually happening,” said Sayeh. “We saw it in Rwanda as it adopted more advanced institutions to rebuild from a devastating conflict … we saw it in Seychelles as it undertook comprehensive economic and institutional reforms to decisively tackle its 2008 debt crisis … and in Botswana, we saw the development of a good policy framework to prudently manage the wealth from mining resources … today these countries lead the region in sound governance, but many others are also taking decisive steps … we have seen good fiscal governance reforms in countries such as Gambia and Senegal. Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mauritius, and Ghana have enacted anti-money laundering frameworks.”

In Kenya, the new constitution adopted in 2010 brought about an era of structured citizens’ involvement in governance, captured as public participation. It enshrined citizens’ rights to be involved in policymaking, both at the national government level and at the county government level; the new units of the devolved system of government. This dispensation gave citizens at the lowest level of administration an opportunity to take part in discussions, decision-making and scrutiny of governance processes. Participation and inclusion, therefore, form part and parcel of Kenya’s governance processes.

As Karuti Kanyinga, a research professor of development studies and governance expert from Kenya, noted, the drafters of the Kenyan constitution had in mind an approach where people would provide input in decisions affecting their lives, which would also provide them with checks and oversight on what government at both levels were doing.

Vibrate Space community recording studio founder Sandy Alibo welcomes US Vice President Kamala Harris at the Freedom Skatepark in Accra, Ghana, March 2023. (Photo: Nipah Dennis/AFP)

“Public participation was specifically embedded in public decision-making to prevent government officials from thinking for people, where they have scored poorly,” Prof Karuti said. “One key output of public participation is that it helps people identify projects or issues.”

Similarly in Ghana, which is touted as a beacon of multiparty democracy on the continent, since the return to constitutional rule in 1992, the country has innovated and implemented several programmes and mechanisms aimed at promoting inclusive citizen participation. For example, the government allows its citizens to participate in the budget process by sending in their input.

Inclusion is an important element of governance and marginalising some people risks neglecting key elements of both the problem and the potential solution. Governments, therefore, must engage more with people, especially by harnessing and unlocking the full potential of the youth. In this respect, Africa’s demographic dividend is a big economic opportunity, but to earn that dividend African countries must meet the aspirations of the new generation.

One of the excuses given for the failure to include youth in crucial decision-making positions is that they lack experience. But young people have fresh ideas, energy, and the creativity required to move society forward. Including youth in decision-making is not only right, but also the wise thing to do, especially given Africa’s predominantly youthful population (more than 60% of Africa’s population is under the age of 25, and as the World Economic Forum has noted, by 2030 young Africans are expected to constitute 42% of the world’s youth).

Crucially, African countries are increasingly realising the importance of giving youth a sense of belonging in respect of governance. A few countries have initiatives and national youth policies aimed at empowering that constituency. Countries are also integrating youth participation into policies and programmes.

In Morocco, for example, the World Bank has devised interventions to support and bring voice to the youth movements in the public sphere and more formal venues of decision-making, including delivery of quality services and the monitoring of local accountability and placing young people centre stage of Morocco’s development. Also, youth participation in the development and implementation of national youth policy has been strengthened through institutional channels – youth councils. Most importantly, the programme was designed to build youth capacity in exercising their civic duties and improving public policy on youth issues.

Tunisia’s new constitution also recognises youth as a driving force in the building of the nation. The World Bank’s 2014 report ‘Breaking the Barriers to Youth Inclusion’ indicates the opportunities for youth participation in community and political processes at local and national levels. These include the creation of institutional channels like youth councils to strengthen participation in the development and implementation of youth policy, and the provision of incentives for youth-led non-governmental organisations and community development groups. Subsequent reports show advances in youth participation in decision-making since 2012.

Ethiopia, one of the countries in Africa with a hefty demographic of youthful citizens (it is estimated that 41% of Ethiopians are under the age of 15) has embarked on a series of political and institutional reforms to create more accountable and transparent governance. The government has been making efforts to ensure all-round active participation of youth by creating conducive conditions for their involvement. Noteworthy, compared to other countries in Africa, Ethiopia has a large proportion of lower house members of parliament under the age of 30 and a high voter turnout.

Protesters chant slogans in a “Youth March for the Climate” demonstration in Casablanca, Morocco, in September 2019. (Photo: Fadel Senna / AFP)

Youth representation and participation have also benefited from African Union programmes such as the New Partnership for Africa’s Development and the adoption of its 2009–2018 10-year plan of action to facilitate and accelerate youth empowerment and development – to ensure effective and more ambitious investment in youth programmes and increased support for the development and implementation of national youth policies. Most importantly, the AU’s Agenda 2063: The Africa we Want, hopes for “an Africa whose development is people-driven, relying on the potential of the African people, including women and youth”.

Elsewhere, Rwanda’s 2003 constitution has been cited as an example of inclusion; article 9 provides for at least 30% participation and representation of women in all arms of government. At the executive level, the country has, since 2010, exceeded these constitutional requirements. Rwanda provides an example of good practice for other African countries to follow and illustrates the potential benefits of implementing measures to increase inclusiveness.

According to the Women’s Political Participation 2021 Africa Barometer report, Rwanda has 61% women’s representation in parliament. South Africa (46%), Namibia (44%) and Senegal (43%) have also made positive strides with levels of women’s representation in parliament, followed by Algeria (26%), Kenya (22%), and Somalia (24%), who have made notable progress in women’s representation in parliament over the past decade.

Raphael Obonyo is a public policy analyst. He’s served as a consultant with the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). An alumnus of Duke University, he has authored and co-authored numerous books, including Conversations about the Youth in Kenya (2015). He is a TEDx fellow and has won various awards.