The year 2023 marks two decades since the official launch of the Kimberley Process (KP) certification scheme.

The certification process is an administrative response to a practical problem: enforce a certificate of origin attached to all shipments of rough diamonds to control and protect the legitimate rough diamond market and stem the flow of conflict diamonds defined as “rough diamonds used by rebel movements or their allies to finance conflict aimed at undermining legitimate governments”.

Towards this objective, it has been a success. The KP claims its members are responsible for stemming 99.8% of the global production of diamonds that meet this definition. But its limitation to non-state perpetrators continues to be the point of contention.

The prevalence of high-demand energy transition minerals in countries with less developed mining sectors with weak regulatory regimes has once again placed soft law under renewed scrutiny, especially on issues of traceability and human rights protection.

The KP offers important lessons on the effectiveness and replicability of these initiatives, especially regarding their complementarity and relation to hard law, the centrality of the state, tensions between governing actors, and the interface between formal supply chains and artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM).

New attention is being placed on institutional governance of the extractive sector. A World Universities Network project, led by the University of Cape Town, is investigating the specific institutional mechanisms for ensuring accountable use of resource revenues for development – including soft law initiatives.

Since the 1990s soft law institutions have become an important part of the extractive sector’s global governance, filling critical regulatory deficiencies and gaps. Companies recognised that they faced existential threats from consumers and shareholders if they did not take their corporate responsibilities more seriously. And home governments responded to citizens’ demands for greater action against corporations.

The formation of the KP resulted from a three-year process that brought together an assemblage of stakeholders from governments, civil society, and companies. This tripartite approach was complementary to, and inspiration for, several other voluntary institutions and non-binding initiatives that govern the extractive industry globally – broadly categorised as soft law.

For example, the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI) promotes improved governance of revenues, and the Voluntary Principles (VPs) on Security and Human Rights provide guidelines on security relationships in the extractive sector.

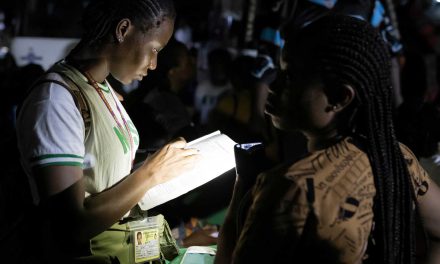

An illegal miner displays his diamonds found scattered in the sandy deposits of a disused mine along South Africa’s Namaqualand coastline. (Photos: Alexander Joe/AFP)

With momentum building for greater accountability mechanisms on companies and protection of human rights, in 2011 the UN Human Rights Council endorsed the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which codifies companies’ responsibilities and has subsequently become an overarching framework for other initiatives.

In most instances, the web of soft law complements but does not replace hard law. Voluntary initiatives can provide the tools to help companies and governments comply with international law or legal restrictions in home countries or export markets.

Shawn Duthie, an associate director at Control Risks, notes: “The Kimberley Process is a good example of non-binding legislation which has seen a positive shift in companies’ behaviour, helped by a growing interest from regulators who are increasingly scrutinising the integrity of global supply chains and looking to implement a number of new regulations, laws, and protocols.”

While membership of the KP is voluntary, it requires its members to “amend or enact appropriate laws or regulations to implement and enforce the certification scheme and to maintain dissuasive and proportional penalties for transgressions”. As such, it transcends the distinction between hard and soft law. This sets it apart from other initiatives, which are often purposefully non-binding to provide best practice guidance without the threat of legal enforcement – a common criticism of their effectiveness and enforceability.

Ultimately, a regulatory framework only has its desired effect if the government has the capacity and motivation to implement it. The credibility of the KP lies with the credibility of participating governments’ claims that their diamonds for export were mined where they say they were.

Many, though not all, soft law institutions are state-centric. For example, the KP and EITI have only states and intergovernmental bodies such as the EU as members, buttressed by civil society, companies, and industry bodies as observers and supporters.

Criticisms of the centrality of the state across soft law institutions manifest in many ways but there are three key concerns.

Firstly, the challenges relating to the accountability of governments to domestic stakeholders in limited-access orders result in inconsistent levels of compliance among members.

Secondly, international accountability and peer review have been an integral part of the success of these institutions in some cases. But the fierce defence of the primacy of national sovereignty, especially in post-colonial African countries, has restricted institutional capability to truly hold state wrongdoing to account between peers.

And thirdly, there has been a long-held perception amongst many African political leaders that these institutions are dominated by powers of the Global North, especially given their origins, and that as such they are part of an exertion of western undue influence over Africa. Such views are once again gaining traction as increased international environmental protection criteria are interpreted by some as preventing African leaders’ desires to exploit fossil fuel deposits.

In the case of the KP, these three tensions coalesce around the central definition of a conflict diamond. Progress on reform is slow and is testing the KP’s in-built review mechanisms conducted through its working groups.

Since its inception, there has been significant pressure from civil society and industry groups to expand the definition of “conflict diamonds” to include national governments accused of human rights abuse.

In 2011, international NGO Global Witness, a founding partner of the KP, ended its formal involvement with the process citing state-sponsored abuse in Zimbabwe, Venezuela, and Cote d’Ivoire as examples where the process had failed to stop the link between the diamond trade and violence.

Proponents argue that had states been included in the original wording few diamond-producing states would have signed up. Twenty-two African states are members of the KP, and its inception was originally driven by many of these diamond-producing states. Twelve out of the 13 members of the civil society coalition observer group are African organisations. And in 2024, the KP will have a permanent secretariat for the first time, which will be hosted in Botswana.

However, the process now faces a bigger challenge. The Russian aggression against Ukraine has brought directed attention towards the link between diamond revenues and inter-state conflict. This challenges the definition and enforcement of the KP, and questions participants’ roles as both players and referees. Ukraine strengthened its challenge this year, quoting the preamble “that state sovereignty should be fully respected”. The United States and EU also made robust challenges against Russia, questioning the integrity of the process.

Last year, an ad hoc committee on review and reform was created and tasked with, among other things, revisiting the definition of conflict diamonds. Angola and South Africa were made chairs and co-chairs respectively. These political dynamics have reignited pressures for reform.

Two decades of experience, collaboration, and development of more efficient processes and practices, including empowered working groups, may place the KP in a strong position for reform. But the use of the plenary as a forum for competing national interests that are informed by realpolitik external to the diamond industry may place this at risk.

Pressures to expand the KP exemplify a wider debate across the organisations that govern soft law instructions – between the ambitions for expanded membership and relevance, versus the requirement of maintaining the institution’s integrity as a means of industry governance.

Meanwhile, one of the key challenges facing the mining industry is the relationship between formal and informal actors. Many countries view artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) as an issue of law enforcement. Yet it is often the countries with the least financial resources that face the largest challenge of alluvial deposits of different minerals and gemstones. ASM can be intricately linked to de-agrarianisation and rural non-farm employment, which are important for economic growth and development. Yet farming communities and agrarian societal voices are often ignored in policy debates.

Since 2004, the KP has been seeking to address the challenges of ASM, and a working group on artisanal and alluvial production was established in 2007. However, governments have focused primarily on formalising or quashing alluvial production, rather than harnessing its benefits.

Companies have once again been at the forefront of driving wiser reform and progress within the sector. In 2018, in Sierra Leone, De Beers piloted their GemFair programme, designed to help formalise ASM and allow miners access to formal markets.

Feriel Zerouki, Senior Vice President of corporate affairs at De Beers says,“De Beers Group’s GemFair programme was launched in recognition of the contribution of ASM producers to the global diamond industry and the vital role it plays in supporting livelihoods. GemFair connects artisanal and small-scale miners to the global market through digital technology and assurance of ethical working standards. Our focus on building partnerships with miners to promote formalisation provides a best practice example to governments and industry of how to harness sector opportunities through inclusion and the implementation of effective policy responses.”

Similar programmes have been trialled by miners of other commodities in Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo – jurisdictions with significant deposits of critical minerals cobalt and lithium, which the EU, US, and UK are keen to access.

In conclusion, the KP and other soft law initiatives remain somewhat constricted by their non-enforceable nature and reliance on states. But, when implemented properly, they provide space for civil society to enjoy genuine participation in resource governance.

More cohesion is needed between these institutions. The possibility for more institutions to fill ongoing gaps will require improved communication from key government and corporate players on the complementarity of these institutions. As the number of initiatives grows, it may seem unclear as to the added value each one brings.

The centrality of the state, and variable interaction with hard law, means that the success of soft law in supporting broader development remains dependent on political will.

However, conscientious consumers are creating incentives for companies, which are increasingly seeing environmental, social, and governance performance as part of the marketing value of their products, to go beyond the immediate requirements of these initiatives.

Christopher Vandome is a Senior Research Fellow on the Chatham House Africa Programme. He is also a PhD candidate in International Relations at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, writing on mining investment in Africa.