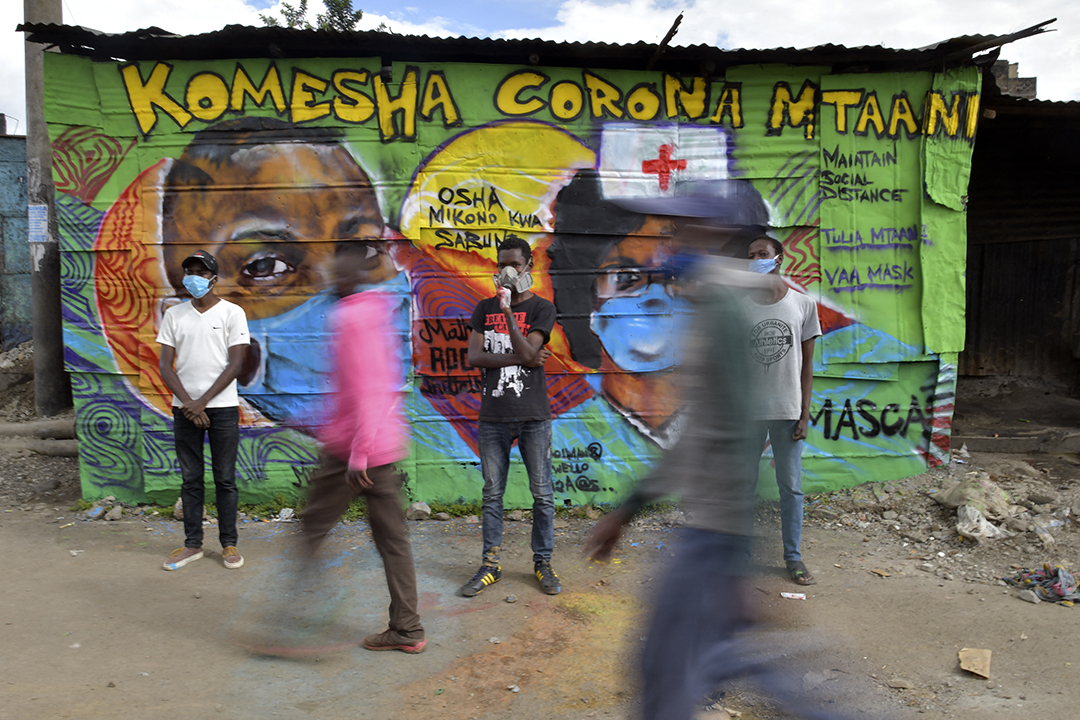

Graffiti artists from Mathare Roots Youth Organisation in front of their latest mural advocating safety practices to curb the spread of COVID-19 at Mathare in Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. Photo: Tony Karumba/AFP

The youth make up 75% of sub-Saharan Africa’s total population. Even at a broader level, almost 200 million people aged between 15 and 24 live in Africa. It has the youngest population in the world. In addition, some 60% of the continent’s unemployed population is made up of young people.

Another, sometimes overlooked, challenge posed by Africa’s youthful unemployed is a growing trend of educated but jobless young people. Based on current trends, 59% of 20-24-year-olds will have secondary education in 2030 compared to 42% today.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the unemployment problem, since large numbers work in the informal sector, which bore the brunt of the virus. Speaking on the World Economic Forum’s podcast series, World vs Virus, last year, Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, one of the African Union special envoys on the continent’s response to the pandemic said: “A high proportion of Africa’s work force operates in the informal economy – more than 70% in some urban areas – earning enough to live day by day. Being unable to work due to lockdown restrictions leaves many of these people without a livelihood.”

It has been estimated that more than 20 million jobs will be lost in Africa due to the COVID-19 crisis. These job losses are likely to impact Africa’s youth more because of the youth demographic, hence the need for effective job creation interventions in the post-COVID-19 period.

Indeed, COVID-19 has affected many programmes that African governments had initiated to create jobs among the youth. For instance, Nigeria’s effort to complement oil dependency by diversifying into the agricultural sector for young people was thrown into disarray by COVID-19, which came with serious restrictions.

At the beginning of 2020, the government of Nigeria launched the National Young Farmers Scheme, designed by the National Agricultural Land Development Authority (NALDA) to spur more youth interest in farming, as agriculture remains the backbone of the country’s economy and the largest contributor to the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). But the combined effects of COVID-19 and low oil prices have derailed progress.

An Ethiopian refugee youth kicks a ball at Um Raquba camp in Sudan’s eastern Gedaref state, on November 28, 2020. – Sudan needs $150 million in aid to cope with the flood of Ethiopian refugees crossing its border from conflict-stricken Tigray, the UN refugee agency chief said during a visit to a camp. (Photo by ASHRAF SHAZLY / AFP)

Another example is Zambia, where fluctuating global copper prices had led the country to look at diversifying into agriculture, labour-intensive sectors and entrepreneurship as a solution to youth unemployment in the country. This plan was also affected by COVID 19 through demand and supply shock and a precarious debt burden. Zambia’s debt had been considered unsustainable before the pandemic struck, and the pandemic made matters worse.

If not properly dealt with, high unemployment levels among the youth pose a significant security threat and potential disruption in some African countries. Unemployment has the potential to lead to unrest, crime and vulnerability to joining extremist groups, as has happened with Al Shabaab in Somalia, where youth are recruited even from neighbouring countries. Governments across the continent will, therefore, face a major test when those who have lost jobs cannot be accommodated back in their economies once COVID-19 is fully tackled.

A recent event to promote hand washing in Korogocho, a major slum in Nairobi, Kenya, testifies to the gravity of the challenge posed by dissatisfied youth when the event turned dramatic, with young people protesting that they had been washing their hands, in preparation to eat, but they lacked something to eat. There is a great societal need across the continent to rebuild faith (in governance institutions) among the youth.

First, countries must embrace ideas from young people. Liberia has taken the lead in establishing a National Youth Task Force Against COVID-19 that is seeking specific solutions to COVID-19-related challenges among the youth.It is also important to point out that governments across Africa have crafted many policies to address unemployment among the youth, but most lack the political goodwill to implement and actualise them.

Young people must also use this COVID-19 period to think outside the box, and not just rely on government. They can, for instance, innovatively organise themselves at the local level and seek support from investors and development partners by explaining how they can offer solutions to problems facing society. Small, micro and medium enterprises, which can easily evolve from such initiatives, play an essential role in the overall growth of the industrial economy of Africa, and they are a vital industry for inclusive socioeconomic development.

Such a coordinated approach should also guide in developing sound policies that take a participatory approach. Ethiopia, Gabon and Nigeria are already moving in that direction. They are reorienting their strategic priorities and investing in sustainable, environmentally friendly development, setting up industrial ecosystems to accelerate their energy transition.

Cristina Duarte, the special adviser on Africa to the UN Secretary-General, points out that economic growth has not generated social inclusion through employment creation, failing Africa’s youthful population, who have not derived any benefit.“Grasping the opportunities that all crises very subtly conceal is extremely difficult,” she says. “But the prospects brought by the COVID-19 crisis for Africa must be seized. In a normal situation, and within a framework of routines, it would be almost impossible to generate disruptions as deep as those triggered by the current crisis.”

A skater performs a trick during a skaters gathering to celebrate Youth Day in Soweto, Johannesburg, on June 16, 2021. – June 16, 2021 marks 45 years since Soweto’s students took to the streets to protest against the use of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction. More than 200 people were killed when 10 000 people took part in the protest action on June 16, 1976. (Photo by GUILLEM SARTORIO / AFP)

Indeed African governments must foster an enabling environment for youth innovation and participation in development – meet their innovation needs, promote and support required legislation and policies, mainstream youth in all relevant aspects of development, and work with them as partners and not mere beneficiaries. However, some young Africans are already turning the COVID-19 crisis into an opportunity to offer innovative digital solutions to address challenges posed by the pandemic. Examples include mSafari, a company that has introduced a contact-tracing application for travellers, created by FabLab, an information and communication technology (ICT) hub in Kenya.

In Morocco, there is Wiqaytna 6, an application that notifies people when someone they have been in contact with tests positive for COVID-19; Global Mamas in Ghana, which is producing reusable masks and has automated, contact-free, solar-powered hand-washing stations using locally sourced materials, to name just a few.

Charles Leyeka Lufumpa, acting chief economist and vice president for economic governance and knowledge management at the African Development Bank Group, says more money should be earmarked for scientific, economic and social research. He argues that countries should pursue global and continental partnerships to prepare for eventualities.

Private sector growth and revamping education and labour markets for the future of work are also key.“Africa needs robust policy responses from every country on the continent, paired with strong support from its development partners,” says Lufumpa. “The continent’s youthful and innovative population, its growing middle class, its value addition to the abundant natural resources, and its ever-improving governance systems give us plenty of reason to be confident that Africa will overcome the ravages of the coronavirus pandemic,” he adds.

If the 2019 Global Innovation Index (GII) is anything to go by, poor standards of education, low investment in research and the uneven adoption of innovative processes, products and solutions by businesses have held back innovation in many African countries. As UNDP former head Hellen Clark remarked, on 19 July, 2014, (at the G20 Young Entrepreneurs Alliance Summit, on UN Action on Youth Employment and Entrepreneurship, in Sydney, Australia) with youth comes energy, vibrancy, and optimism. Young people are only asking for a supportive environment and opportunity.

Such a coordinated approach should also guide in developing sound policies that take a participatory approach. Ethiopia, Gabon and Nigeria are already moving in that direction. They are reorienting their strategic priorities and investing in sustainable, environmentally friendly development, setting up industrial ecosystems to accelerate their energy transition. Cristina Duarte, the special adviser on Africa to the UN Secretary-General, points out that economic growth has not generated social inclusion through employment creation, failing Africa’s youthful population, who have not derived any benefit.

“Grasping the opportunities that all crises very subtly conceal is extremely difficult,” she says. “But the prospects brought by the COVID-19 crisis for Africa must be seized. In a normal situation, and within a framework of routines, it would be almost impossible to generate disruptions as deep as those triggered by the current crisis.”

Indeed African governments in Africa must foster an enabling environment for youth innovation and participation in development – meet their innovation needs, promote and support required legislation and policies, mainstream youth in all relevant aspects of development, and work with them as partners and not mere beneficiaries.However, some young Africans are already turning the COVID-19 crisis into an opportunity to offer innovative digital solutions to address challenges posed by the pandemic. Examples include mSafari, a company that has introduced a contact-tracing application for travellers, created by FabLab, an information and communication technology (ICT) hub in Kenya.

In Morocco, there is Wiqaytna 6, an application that notifies people when someone they have been in contact with tests positive for COVID-19; Global Mamas in Ghana, which is producing reusable masks and has automated, contact-free, solar-powered hand-washing stations using locally sourced materials, to name just a few.

Charles Leyeka Lufumpa, acting chief economist and vice president for economic governance and knowledge management at the African Development Bank Group, says more money should be earmarked for scientific, economic and social research. He argues that countries should pursue global and continental partnerships to prepare for eventualities. Private sector growth and revamping education and labour markets for the future of work are also key.

“Africa needs robust policy responses from every country on the continent, paired with strong support from its development partners,” says Lufumpa. “The continent’s youthful and innovative population, its growing middle class, its value addition to the abundant natural resources, and its ever-improving governance systems give us plenty of reason to be confident that Africa will overcome the ravages of the coronavirus pandemic,” he adds.

If the 2019 Global Innovation Index (GII) is anything to go by, poor standards of education, low investment in research and the uneven adoption of innovative processes, products and solutions by businesses have held back innovation in many African countries. As UNDP former head Hellen Clark remarked, on 19 July, 2014, (at the G20 Young Entrepreneurs Alliance Summit, on UN Action on Youth Employment and Entrepreneurship, in Sydney, Australia) with youth comes energy, vibrancy, and optimism. Young people are only asking for a supportive environment and opportunity.

Raphael Obonyo is a public policy analyst. He’s served as a consultant with the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). An alumnus of Duke University, he has authored and co-authored numerous books, including Conversations about the Youth in Kenya (2015). He is a TEDx fellow and has won various awards.