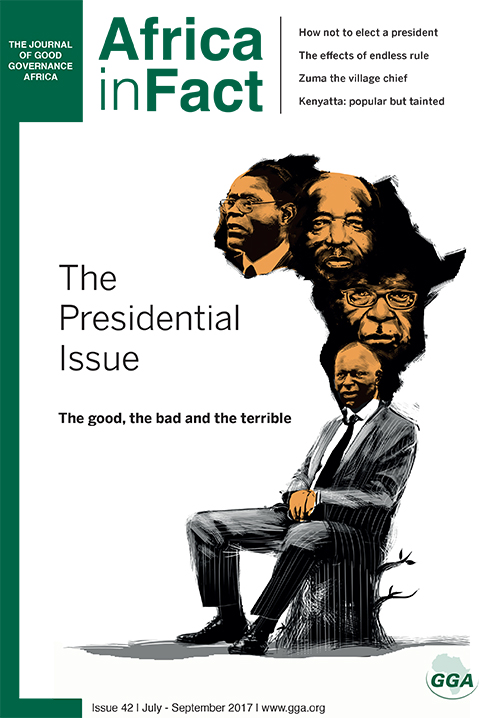

The role of presidents is currently one of the hottest topics in Africa, hence the theme of this edition of Africa in Fact: “The Presidential Issue”. Nelson Mandela once said, “In my country we go to prison first, and then become president.” Recently, however, there have been calls for this sequence to go the other way. Presidents who abuse their office ought to be removed from power and jailed, many say. But what makes a good president? How do we define a successful presidency?

Ranging across the continent, our contributors provide insightful historical analysis, portraits of the colourful individuals who occupy the role of presidents around Africa, evaluations of presidential systems and specific instances of good – and bad – executive management. Some of our writers even attempt to provide predictions as to where we may be headed.

In the African context, of course, the problem of “Big Man” politics arises. The “big men” of Africa often defiantly refuse to step down, with even a little humility – mirroring the archaic practices of their former colonial masters and effectively reducing many of their people to modern-day slavery. To help us understand how they stay in power,

Lukhona Mnguni analyses Africa’s presidential electoral systems: direct (election by the public), parliamentary (election by parliament) and “stage-managed democracies” (sham elections). Parliamentary systems may not be a magic cure for some of the ills of governance, but they go some way to mitigating what Terence Corrigan refers to as “the cult of personality”.

On the other hand, under parliamentary systems, presidents appear to hold themselves more accountable to the political parties who vote them in than to the people. The question of term limits is a theme that runs through many of the articles in this edition. The refusal of some presidents to accept limits to their time in office represents one of the greatest challenges to the consolidation of democracy on the continent. Consider Paul Kagame, who recently secured another term in office through what our writer terms a “constitutional coup”, and may be in power until 2034. In so doing, he is seeking to join the dubious company of some of the world’s longest ruling (let us not use the word “serving”) leaders, among them Eduardo dos Santos, Teodoro Obiang and Robert Mugabe.

The Old Boys club of rulers who hold on to power for life never seems to have quite enough members, and they rarely, if ever, step down graciously. Africa, our continent, is the Jurassic Park of executive authority, with post-independence fossils grinding their deceptively large, but intrinsically fragile skeletal structures through the halls of power. Don’t be fooled by their lame appearance, however. These dinosaurs from the pre-democratic era do, indeed, hold immense power. Only, they are mainly interested in securing their legacy, which means gain for family and friends via networks of patronage that thrive on corrupt and nepotistic practices.

In this regard, Ntibinyane Ntibinyane’s crisp coverage of African involvement and exposure in the Panama Papers is instructive and well worth the effort it dedicates to all the presidents’ men, and women. As Dianna Games observes, many African leaders deliberately choose to perpetuate poverty and underdevelopment, to promote vested interests and political expediency. Genuine succession planning, serving the national interest? These ideas are the last thing on the minds of people involved in wealth accumulation that is infinitely more primitive than that observed by Marx.

It is as well to be critical, but speculation won’t end the dinosaurs’ rule. The plural of “anecdote” isn’t “data”. Mindful of this adage, Vaughan Dutton of Oxford University has mined Africa Survey – our compendium of data – for specific presidential indicators.

He detects some trends underlying the above reflections: namely, that the longer a president remains in power, the more likely his or her country is to suffer abuse of power and mismanagement. We see this in the case of the DRC with Kabila Jr – or perhaps more appropriately, Kabila Inc. (see William Clowes and Ntibinyane), Equatorial Guinea (see Wilson Johwaon Obiang) and, not least, Mugabe’s Zimbabwe (see Peta Thornycroft).

William Gumede offers an analysis of Jacob Zuma’s presidential style in the context of revelations of his and his friends’ nefarious activities of “state capture”. Helen Grange evaluates the presidential succession race in terms of battles between “traditionalists” and “reformers”.

The characters mentioned above constitute a familiar trope, but the continent is also home to more complicated cases involving reform-orientated leaders. Consider Nigeria under the leadership of Muhammadu Buhari and Tanzania with John Magufuli (see articles by Joseph Adeyeye and Nick Branson respectively). Both countries are seeing notable attempts to promote good governance, though the former appears to be tackling the problem in a more sustained way.

There are also more ambiguous cases. Paulo Inglés gives Angolan president Dos Santos a “fail” on his overall performance, due to his last phase in office. John Paul Wafula awards a similar result to Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya, who appears to have harnessed domestic support at home but faces continued criticism over governance and corruption. Joel Konopo likewise gives a lukewarm reading of the career of Ian Khama of Botswana. Yunus Momoniat reviews a recent book on the continent’s best and worst leaders that finds very few in the former class.

What is clear that challenges of executive leadership remain a concern in Africa, as they do elsewhere. The time appears to be ripe for a new generation of young African leaders – young at least by comparison with some of the hoary old crocs still navigating the continent. One such incumbent is Adama Barrow, president of the Gambia. Modou Joof discusses his case with interest, noting his humble first 100 days and the difficulties that will be encountered by any reforms undertaken there thanks to the legacy of Yahya Jammeh.

Will the generic “Big Men” of Africa survive? Mark Twain said it well: “The report of my death has been exaggerated.” As for us, only time will tell. For now, Africa remains en marche!

Alain Tschudin is Executive Director of Good Governance Africa. He is a registered psychologist with Ph.D.s in Psychology and in Ethics. He was a Swiss Academy Post-doctoral Fellow at Cambridge and oversaw the Conflict Transformation & Peace Studies Programme at UKZN for several years. He has broad research and community engagement interests and has worked for various universities in Africa and Europe, with the European Commission, with local and international NGOs, as CEO of a leadership development agency, and as lead consultant for Save the Children and UNICEF, most recently as Child Protection Assessment Coordinator for Northern Syria. Alain has an adjunct association with the International Centre of Non-violence (ICON) and the Peacebuilding Programme at the Durban University of Technology.

ALAIN TSCHUDIN is a former Executive Director of Good Governance Africa. He is a registered psychologist with Ph.D.s in Psychology and in Ethics. He was a Swiss Academy Post-doctoral Fellow at Cambridge and oversaw the Conflict Transformation & Peace Studies Programme at UKZN for several years. He has broad research and community engagement interests and has worked for various universities in Africa and Europe, with the European Commission, with local and international NGOs, as CEO of a leadership development agency, and as lead consultant for Save the Children and UNICEF, most recently as Child Protection Assessment Coordinator for Northern Syria. Alain has an adjunct association with the International Centre of Non-violence (ICON) and the Peacebuilding Programme at the Durban University of Technology.