Raila Odinga at the World Economic Forum, Davos, 2013 © WEF/Michael Wuertenberg

The continent’s systems of governance are evolving, but a transnational approach may be needed to ensure a system that works for the citizenry

In Africa, by 2005, about 40 countries had introduced democratic systems of government since independence by having “regular, competitive multi-party elections”. Others, however, have remained under authoritarian rule, as indicated by Greg Mills and others in their recently published book, Making Africa Work.

The major democratic trends observed in most African countries since then include: the embrace of elections, the acceptance of constitutional norms, the emergence of free media, an active civil society and the establishment of regional conventions and protocols, according to Emmanuel Gyimah-Boadi, a professor of political science at the University of Ghana.

This article will focus on the continent’s embrace of elections and evaluate the different electoral systems, especially as they concern the election of presidents.

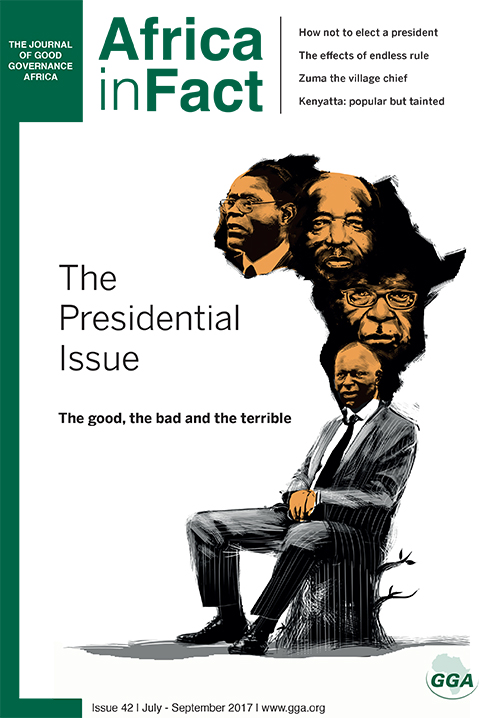

Three main presidential electoral systems can be identified: constituency- based presidential systems (president elected by the electorate directly), parliamentary executives (president elected through parliament), and stage- managed democracies (incumbent presidents use the appearance of democracy to extend their time in office).

Presidential systems lend themselves “far more to big man politics”, unlike parliamentary executive systems such as the South African model, in which the National Assembly elects the president from among its members, says Sithembile Mbete, a political science lecturer at the University of Pretoria.

Presidential systems are also susceptible to ethnicist politics, which has been a major complicating factor to the introduction of democracy in Africa, argues Dennis Mwaniki, a researcher and policy analyst at the Africa Policy Institute, based in Kenya.

Ethnic dominance, allied with a presidential system, introduces or plays on rifts between majority and minority ethnic groups, which can result in inter-group violence. “Majority ethnic groups tend to dominate, politically locking out small and minority tribes,” he told Africa in Fact.

However, the parliamentary executive system also has drawbacks, both commentators agree. One of these is the risk that a president who is elected by parliament may not feel accountable to the broader electorate, but rather to the political party elites who supported him or her.

Meanwhile, stage-managed democracies involve obvious risks for the countries in which they occur. “Ruling presidents and parties flagrantly exploit the advantage of incumbency, abuse [state] resources, and unleash physical intimidation on voters in the pursuit of victory,” says Gyimah-Boadi. To add insult to injury, the presidents then pronounce the elections in which they used state resources and unlawful means to win as “free and fair”, he says.

Raila Odinga, a Kenyan opposition leader, has argued that such an approach represents an “assault on democracy”.

“Elections are now held as rituals designed to perpetuate the rule of the incumbent,” he remarked in 2016, delivering a talk at Chatham House in London under the title “The Importance of Democracy in Africa: Kenya’s Experience”.

Electoral competition has increased in African politics since the 1960s, when only two of 26 presidential elections were contested. By the 1990s, some 90% of presidential elections were held on a competitive basis, reaching about 98% in the period between 2000 and 2005, according to a 2007 study by Daniel Posner and Daniel Young, two noted US researchers on African politics.

However, even with this improvement, “in most African polities, one party has an absolute majority of seats in the legislature and can govern alone,” according to a 2004 paper by Matthijs Bogaards, a professor of political science at the Central European University. Given such dominance, there is a clear risk that such elections could result in “big man” politics.

“Big man” politics occurs either through legal means, if extensive powers are constitutionally conferred on a president, or through the power of the gun, says Mwaniki. The electoral and political systems of many African states give a preponderant amount of power to the leader, “with few checks and balances”, says Mbete. Where checks and balances are in place, the dominance of the system by one party erodes the possibility of accountability by allowing “politics of complacency”.

In addition, Mwaniki suggests that the prevalence of “big man” politics in Africa is not only structural, but due to “a defect in character among the Africa leaders who … think that… no other person … can lead their countries”. There are indications that both elements play a role in Africa’s continued tendency to “big man” politics.

Around Africa, elected presidents who want to extend their stay in power are increasingly attempting to do so through formal processes. Posner and Young argue that Africa’s embrace of democracy in recent decades has been an important step in curbing the brazen practices of the continent’s “big men”.

Some “big men” still succeed. In December 2015, for instance, President Paul Kagame of Rwanda won a referendum that allowed him to run for a third term in 2017, paving way for other potential terms; he might well remain in power until 2034. Other presidents trying the same thing have, however, found their way to untrammelled power opposed by constitutional measures.

Clearly, the seductions of power can turn even well-meaning people into tyrants, as shown by the cases of Abdoulaye Wade, a former president of Senegal and Olusuegun Obasanjo, a former president of Nigeria.

When he came into power in 2000, Wade was seen as an important proponent of good governance on the continent. He worked hand-in-hand with other leaders thought to represent good governance, among them former President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa and Obasanjo, to pioneer the African Union and NEPAD, for instance. Yet it is instructive that each of these leaders fell into the trap of thinking that no one else was capable of leading their nations.

Wade was first elected in 2000, when Senegal’s constitution prescribed a presidential term of seven years. After a referendum, the constitution was changed in 2001 to limit presidential terms to five years. Wade was re-elected in 2007, and pushed for a re-instatement of a seven-year presidential term, which would have required a constitutional amendment. (Bizarrely, he argued that the five-year term limit had not been effect when he took office, and he was therefore entitled to run for another term of seven years.)

In 2012, an opposition politician, Macky Sall was elected president of Senegal. Making good on an electoral promise, Sall held a referendum on constitutional reforms that included the reaffirmation of a limit of two consecutive five-year presidential terms.

In May 2006, Obasanjo attempted a formal process to seek a third term as president of Nigeria, but the Nigerian Senate rejected a bill that would have changed the country’s constitution.

Mbeki is another example of a trend that has seen presidential incumbents trying to extend their stay in office – if, in his case, indirectly. As he approached the end of his second, final term as South African president, Mbeki contested party elections in December 2007 in an attempt to remain president of his political party, the African National Congress (ANC).

Some saw this as an attempt to seek a third term as president of South Africa, but without a constitutional amendment, which would have required a two-thirds majority in parliament, this would not have been possible.

However, retaining the presidency of the ANC would have given him great influence, because he would have had significant control over the party’s “deployees” to government.

Why the need for presidential term limits? Well, they discourage the “president for life” syndrome, as Mwaniki puts it. And by setting limits to the time a leader can spend in office, they can also encourage leaders to set about implementing their policies – especially if they want to be elected for a second term.

Mbete suggests that a five-year presidential system, with the option of reelection, “allows enough time for a focused president to be effective”. But she adds that limits on presidential terms should be context-specific, because the powers and privileges granted to presidents differ from country to country.

We can note here that Uruguay has developed an interesting variation on limiting presidential terms. There, the president can serve a maximum of two five-year terms, but the terms cannot be served consecutively. I would argue that this refinement has the potential to encourage African leaders to focus on, and commit to delivering on their electoral promises within a five-year tenure. In Ethiopia, the president is the head of state, but the role is mainly ceremonial.

Meanwhile, the prime minister “is the Chief Executive, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, and the Commander-in-Chief of the national armed forces”, according to the constitution. The president is nominated by the House of Peoples’ Representatives and his or her election requires a two-thirds majority vote of a joint session of that House and the House of the Federation. The prime minister is elected by a majority vote of the House of Peoples’ Representation.

In South Africa the president “is the Head of State and head of the national executive”, as well as commander-in-chief of the defence force, according to the constitution. In Uganda the president enjoys a designation as the country’s “Fountain of Honour” in addition to more mundane designations such as those describing the role of the president of South Africa.

In Uganda there is a prime minister’s role, but it is effectively ceremonial. Some rather peculiar privileges and immunities are granted to the Ugandan president that are not granted to the presidents of Ethiopia and South Africa. According to the Ugandan constitution, for instance, the president “takes precedence” over all other Ugandans, and cannot face legal prosecution while in office.

Clearly, privileges and immunities of this kind could allow an incumbent president to circumvent the law, to intimidate political opponents and prevent free and fair elections, since no legal measures would be available to prevent this. Moreover, they incentivise the incumbent to try to stay in power, since he or she would avoid criminal prosecution by doing so.

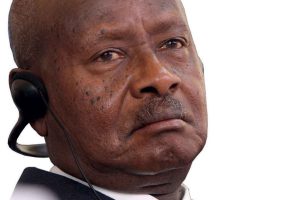

It is no wonder that Yoweri Museveni remains president of the country after 30 years in power. In July 2015 the Democratic Alliance (TDA) a coalition of opposition parties in Uganda condemned the arbitrary leaders, Kizza Besigye and former Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi, as they were en route to launching their presidential campaigns. This was viewed as Museveni abusing state security resources to circumvent strong opposition at the polls.

President of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, 2013 © Foreign and Commonwealth Office arrests of two opposition President of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, 2013 © Foreign and Commonwealth Office

Uganda is a clear example of the kind of sham, stage-managed democracy that Greg Mills and others aptly describe as a “constitutional coup”, in which incumbents use state resources to manage an election process in their favour. According to the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), by June 2015 there had been 16 attempts at such “constitutional coups” around the continent, with 10 succeeding and six failing. The ISS said that this trend posed “the next big threat to peace and security on the continent”.

Aside from the checks and balances included in individual countries’ constitutions and institutions, the African Union (AU) also represents itself as a potential corrective force as regards the powers of presidents. The AU’s collective vision of good governance for the continent is represented in its founding values, prescripts and a range of protocols.

The Constitutive Act of the AU outlines 14 objectives, some of which are to: achieve greater unity and solidarity between African countries and the peoples of Africa; accelerate the political and socio-economic integration of the continent; promote peace, security, and stability on the continent; promote democratic principles and institutions; and promote popular participation in politics and good governance.

Recognising that endemic conflict was both a threat to peace and an impediment to Africa’s development, in December 2003 the AU set up a Peace and Security Council (PSC) as “a standing decision-making organ for the prevention, management and resolution of conflicts. The PSC shall be a collective security and early-warning arrangement to facilitate timely and efficient response to conflict and crisis situations in Africa”.

In an attempt to create a democratic institution, no country has a veto vote on any matter, and no country can have a permanent seat on the PSC. This ensures that all regions of the continent are fairly represented and avoids the problem of legitimacy faced by the UN Security Council.

However, this system too has shortcomings. One of them was indicated to me during a 2013 research study at the AU Headquarters. An ambassador from an African country stationed in the AU Commission’s office told me that the PSC arrangement can result in delays in the decision-making process.

At some junctures, the countries with resources needed to undertake a mission might not be represented in PSC meetings, and a process of lobbying for the needed resources must take place before a resolution that is binding an unrepresented country can be taken. This can lead to the PSC acting too late when serious developments are apace on the ground.

The lacklustre approach of the PSC, and by extension the AU, can be traced as far back as the Libyan crisis in 2011 to recent developments in Burundi, Gambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

But the AU’s ability to foster democratisation around the continent is also compromised by the fact that it does not require member countries to be democratic. “Unlike some other regional organisations, such as the EU or the Common Market of the Southern Cone of South America (Mercosur), democracy is not a precondition for membership in the AU. The AU’s membership comprises the whole gamut of regime types,” writes Frank Mattheis, a senior researcher in global studies at the University of Pretoria.

This raises the question: can an organisation that harbours tyrants within its ranks contribute effectively to the democratisation of the continent? Among the tyrannical presidents tolerated by the AU are Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea (the longest serving president in the world) and José Eduardo dos Santos of Angola (the second longest-serving president). Both took power in 1979, the former on 3 August and the latter on 10 September.

Other notable tyrants include Paul Biya of Cameroon, who has ruled since November 1982, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (having been prime minister since independence in 1980) and Omar al-Bashir of Sudan (since June 1989). In this respect, the AU’s Constitutive Act includes a major defect.

Formally speaking, the AU can intervene in a country where gross human rights violations, and therefore attacks of democracy, are occurring – but it cannot do so without the permission of the government of the affected country. Meanwhile, that government might be a party to the dispute that has generated the need to intervene.

This is partly why the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) seems to have taken the lead in West Africa, moving with greater pace and urgency than the AU to deal with the Gambian political crisis at the end of 2016. The incumbent president, Yahya Jammeh had attempted to hold on to power by blocking the swearing-in of Adama Barrow, who had won election in December. ECOWAS stepped in, declared Barrow’s election legal and facilitated the previous incumbent’s departure, even threatening to send troops if he did not leave office, and the country.

Another problem limiting the AU’s ability to control would-be presidents- for-life is its continued reliance on foreign funding. The AU headquarters in Addis Ababa was built by the Chinese government, for instance, while the Julius Nyerere Peace and Security building, officially opened in October 2016 was funded by Germany at an estimated cost of € 31 million. “While the AU’s budget grew from $278,2 million in 2013 and to $393,4 million in 2015, external financing also rose from 56% to 61,7% in the corresponding years,” writes Ini Ekott in Africa in Fact in January 2017.

Given the possibility of external influence, can African citizens trust that the AU’s main focus is on finding “African solutions for African problems”? So far, it would appear that the failure of African governments to adequately resource the AU has led to the organisation’s inability to develop African forms and practices of governance.

This underfunding of the AU by its own member states indicates their lack of commitment to a regional body that is meant to advance, peace, stability, democratisation and development around the continent. Similarly, doubts have been raised concerning the organisation’s – and its members’ – commitment to developing a regional system of justice that is capable of holding those who commit war crimes and crimes against humanity accountable.

In recent years, these doubts have been compounded by the fact that prominent African countries have used the AU as a forum to encourage mass withdrawals from the Rome Statute, the founding convention for the International Criminal Court.

The absence of a robust, independent and respectable regional system of justice means that Africa does not have a regional institutional deterrent for leaders who abuse power, commit gross human rights violations or preventing the further entrenchment of democracy around the continent.

Senegal’s President Macky Sall © Présidence de la République du Sénégal

Africa’s constitutions, institutions and electoral rules are an important element in limiting the power of potential “big men”. In addition, however, active citizenry will also increasingly be an important influence on the fostering of good governance in Africa. As we have seen, the citizens of Senegal have recently defended good governance by voting Wade out of power, but there are other examples that show that the power of the ballot box and protest is beginning to take effect.

In 2014, in Burkina Faso, citizens went as far as burning parliament, a hotel and some houses in an area where members of parliament resided to encourage the incumbent, Blaise Compaore, to leave power. After 27 years as president, he had attempted to push through a constitutional amendment revising presidential term limits. The government responded repressively but citizens, opposition parties and civil society pressed on until they secured Compaore’s resignation, which triggered the dissolution of parliament. Some ECOWAS leaders assisted with negotiations for a transitional government.

As the Burkina Faso example shows, courageous, active citizenry represents a considerable potential power to resist malfeasance from incumbent leaders, as well as those who attempt to dismantle democratic rules and practices in an effort to overstay their welcomes. But it is not always successful. In Burundi, in 2015, citizen protest failed to prevent Pierre Nkurunziza’s from running for a third term – even though the constitution prohibited him from doing so.

When Burundians protested, they were met by “a ruthless crackdown” that eventually led to the death of about 100 people, a South African commentator, Justice Malala reflected at the time. Many others were injured or displaced – especially those who opposed the president. The military attempted a coup while the president was out of the country, but it failed. Nkurunziza was re-elected in July 2015 and remains the president of Burundi. “What is the point of th.e AU when it loses its backbone at the first sight of a dictator?” Malala asked.

The message here is that good governance is advanced when there is significant interplay between sound and progressive electoral systems that are universally respected, and active citizens who act as a vanguard of good governance and political stability in their own countries, and perhaps, as I will argue, more widely. Africa’s citizens will need to be more politically aware and active.

African countries are increasingly connected through political and economic links, which means that they are also more vulnerable to each other’s failures. “[A country] can be a bastion of prosperity but if your neighbouring countries have free-falling economies, it will ultimately affect you,” Stewart Bailey, senior vice-president of investor relations and group communications at AngloGold Ashanti told a Business Day event in Johannesburg in April 2017. The same is true of political systems.

Citizens will need to develop useful methods that enable them to organise transnational movements for the strengthening of multi-governmental institutions such as the African Union and ECOWAS. One important element of this is the role that academics, intellectuals and thought leaders around the continent can play.

African universities ought to be at the forefront of an “intellectual awakening, which will empower the peoples of Africa to remake our societies and our continent,” former South African President Thabo Mbeki told an All- Africa Students Union summit in September 2010. This suggests to us that transnational social justice movements should develop and exploit knowledge networks.

Taken together, these points indicate one way forward: the development of transnational networks of thought and activism around particular themes and issues. More widely afield, the November 1999 organisation of social movements now known as “the battle of Seattle” showed the ability of people to mobilise across nations and continents. In that case, the groups and networks involved saw themselves as combatting the negative effects of globalisation. In Africa, the Pan-African Treatment Access Movement (PATAM) is another example of transnational advocacy, in this case as regards HIV/AIDS issues.

Such movements have been helpful in holding leaders accountable, as it was seen when the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) of South Africa litigated against the Thabo Mbeki government leading to victory in the Constitutional Court in July 2002 with a judgment that forced government to roll out nevirapine to pregnant mothers. That was another form of active citizenship combining, organising protest and litigation.

As the great nineteenth-century activist for the abolition of slavery, Frederick Douglass so aptly remarked: “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” African citizens must continue to demand good governance, government respect for institutions that support democracy, and upright leadership. Perhaps a transnational social movement dedicated to the full democratisation of the continent is needed.

Lukhona Mnguni holds a Bachelor’s community and development studies (cum laude) and an Honours in conflict transformation and peace studies (cum laude) from the University of KwaZulu-Natal. He holds an MSc in Africa and international development from the University of Edinburgh and is currently a PhD intern researcher in the Maurice Webb Race Relations Unit in the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.