While the involvement of Africans in the Panama Papers scandal has been described as ‘jaw dropping’, the revelations have resulted in very little action being taken

In February this year Jürgen Mossack and Ramón Fonseca, the founding and senior partners behind the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, were denied bail following their arrest under an international warrant that saw a collaboration by prosecuting authorities from various South American states.

Acting with other South American states, Peru, Panama and Brazil are investigating potential exposures of corruption in the “Panama Papers”, a massive leak of documents from the law firm, some of which appear to show that current and former political leaders used the law firm to launder illicit revenue.

In early February, Peru issued an international arrest warrant against its former president, Alejandro Toledo on allegations of corruption. Central to Peru’s investigation is how money leaves the country and disappears without a trace. A web of offshore companies set up by Mossack Fonseca, and situated in tax havens around the world, turned out to be an important key to tracking these illicit flows of money.

South America has taken a strong collaborative stance in respect of the allegations revealed by the Panama Papers. However, Africa, and individual African countries generally, have taken little or no action to investigate leaders named in the papers.

The continent of Africa loses over $50 billion a year through illicit financial flows, according to a 2015 report by a UN High Level Panel led by former South African president Thabo Mbeki. As with South America, the question is how so much illicit money is siphoned out of the continent.

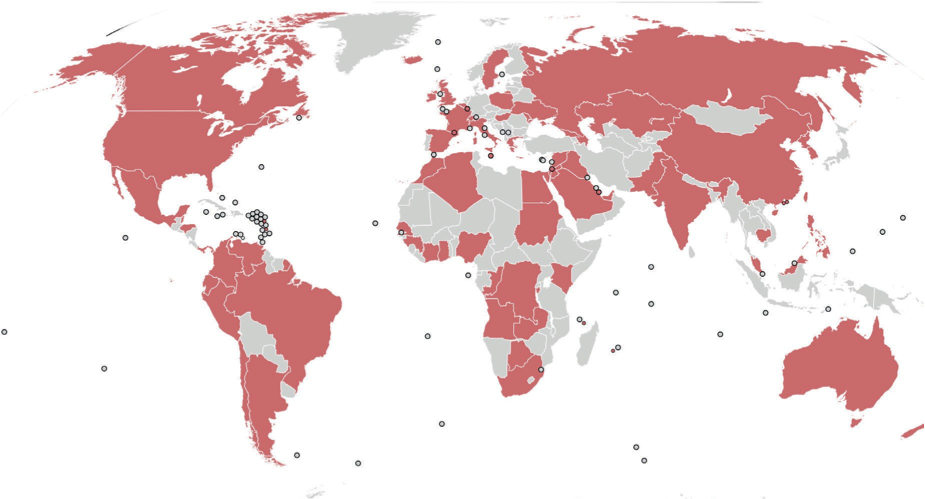

The Panama Papers were investigated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalism (ICIJ), an international cross-border collaboration of over 300 journalists around the world. The Papers offered some important clues as to how illicit financial flows are processed, and where they end up.

In short, the money is illegally moved out of a particular country through a series of shell companies, obscure shareholding agreements and irregular powers of attorney. These vehicles facilitate transfers of money in the form of unrecoverable loans and share transfers to offshore accounts in tax havens.

The leak of the Panama Papers, which comprise some 11.5 million records maintained by Mossack Fonseca, revealed an opaque system that allows the rich and powerful, and criminals, to hide their money. Among other people around the globe, the Papers point a finger at some of Africa’s leaders, including presidents, their associates, family members and even judges as some of the culprits behind illicit financial outflows from the continent.

Together with weak local and international legislation, the legal vehicles created by Mossack Fonseca made it possible for African leaders to circumvent tax and money laundering legislation by hiding their legally and illegally obtained money in offshore accounts.

The electoral and political systems of many African states give a preponderant amount of power to the leader. No African president was found to have personally used Mossack Fonseca to hide money, but there is significant evidence that their family members and associates used the firm to set up companies offshore, and so hide millions of dollars.

Billionaire Jaynet Kabila, twin sister of Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) president Joseph Kabila, was named in the leak as a director of an offshore company called Keratsu Holdings Limited. The company was incorporated in Niue, an island in the Pacific Ocean, in 2001, immediately after her brother assumed power following the assassination of their father, Laurent Kabila.

Keratsu has stakes in Vodacom Group Ltd, one of the major mobile phone operators in DRC. According to the papers, Congolese businessman Kalume Nyembwe Feruzi, a close associate of the Kabila family, is a co-director of Keratsu. Email correspondence obtained from the Panama Papers shows that the company was struck off the Niue company registry in 2003 for non-payment of its annual filing fee, but its registration was restored in 2011 after an undisclosed amount was paid in settlement.

The revelations caused outrage in DRC. Opposition leaders alleged that the family was looting state resources. “Members of the Kabila family have accumulated huge wealth, including stakes in offshore tax havens,” opposition leader and lawmaker Martin Fayulu told Bloomberg. “We need an urgent inquiry and we need to demand the repatriation of these monies to Congo.”

Moving on to Ghana, soon after his father was elected to office in 2001, John Addo Kufuor, son of the former Ghanaian president, John Kufuor, appointed Mossack Fonseca to manage The Excel 2000 Trust. According to records retrieved from the leak, the trust held $75,000 in a bank account in Panama. John junior’s mother, Theresa Kufour was also a beneficiary.

In November 2010, an employee of Mossack Fonseca’s compliance office in the British Virgin Islands raised questions to a colleague about Kufuor’s record. “Due to the apparent prevalence of corruption surrounding Mr. Kufuor we would not recommend us taking him on as a client or continuing business with him.” However, Mossack continued to do business with him until 2012, when he personally asked Mossack Fonseca to close the trust.

The young Kufuor was linked to two other offshore accounts registered in the tax haven of British Virgin Islands (BVI). The companies Fordiant Ltd and Stamford International Investments Group Limited were registered in 2004 and 2007 respectively, at the time when his father was president of Ghana. The companies are inactive, according to the documents retrieved from Mossack Fonseca’s database.

According to Ghanaian media, and during a time when his son was operating offshore accounts, the former president gained lucrative government contracts and private sector business deals through paternal connections while in office. However, an official commission later found no evidence of wrongdoing against the president.

The Panama Papers also revealed that the son of Congo’s long-time ruler president Denis Sassou-Nguesso, and deputy director general of National Petroleum Company of Congo, Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso established an offshore company in the BVI with the assistance of Mossack Fonseca, according to French publication Le Monde. Sassou-Nguesso’s company Phoenix Best Finance Ltd was said to have been incorporated in 2002.

Le Monde also revealed that the name of Lucien Ebata, who is linked to the Sassou-Nguesso family, appears in the Panama Papers. Denis Christel and Ebata are close friends and business associates, according to the Paris-based newspaper.

Ebata runs a company called Orion Group SA, with authorised share capital of $10 million. In 2009, Mossack Fonseca registered the Swiss based company in the Seychelles via a Luxemburg company, Figet, according to Le Monde. “Among its clients are Anglo-Dutch company, Shell, as well as the National Petroleum Company of Congo (SNPC), and Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso, the Congolese president’s younger son and personal friend of Lucien Ebata,” the paper said.

Rym Sellal, the daughter of Algeria’s prime minister, Abdelmalek Sellal, appears in documents linked to the corruption scandal involving a state-owned energy company, Sonatrach. According to ICIJ partner Le Desk, Rym Sellal was a beneficiary of Teampart Capital Holdings Limited, a company formed in the BVI with capital of $50,000.

The company was incorporated in 2004, apparently with the assistance of Omar Habour, a controversial Franco-Algerian businessman. “We ask you to cancel the power of attorney in favour of Mr Omar Habour and to issue one in favour of Miss Rym Sellal,” reads an email sent to Mossack Fonseca by representatives of Habour and Sellal dated 28 February 2005.

The Panama Papers also revealed for the first time the involvement of presidential aides and associates in setting up offshore accounts in tax havens. José Maria Botelho de Vasconcelos, a close ally of the Angolan president, José Eduardo dos Santos, was named as having an interest in an offshore company. He was listed as one of the two people who had power of attorney for Medea Investments Ltd, a company formed in 2001 with capital of $1 million and based in Niue.

Also mentioned in the Panama Papers were: Adeslam Bouchouareb, the Algerian minister of mines and close ally of the Algerian president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika; Ivorian banker Jean-Claude N’Da Ametchi, a friend of former president Laurent Gbagbo; President of the Botswana Court of Appeal Ian Kirby, who is also a close associate of Botswana’s president, Ian Khama; and Emmanuel Ndahiro, a former chief of intelligence in Rwanda who was closely associated with President Paul Kagame.

The extent of the involvement of African presidents, politicians and their families in the Panama Papers was “jaw dropping”, according to Will Fitzgibbon, a journalist who was involved in the ICIJ’s work on the leaked documents. He emphasised that many of the companies and transactions that figured in the papers were not illegal.

“But the choice of politicians to use or benefit from secrecy and, in some cases, to hide illicit wealth, should concern us all. The less we know about what our leaders do, the less accountability we have to make sure they are acting in our interests and spending money wisely on what our societies need,” Fitzgibbon told Africa in Fact.

“The Panama Papers leak might encourage some politicians and their families to think differently about how they acquire wealth and what they do with it, he said. “Others, sadly, will just look for alternative methods of secrecy.”

NTIBINYANE NTIBINYANE is an investigative journalist and co-founder of INK Centre for Investigative Journalism, a non-profit news organisation. He is the former editor of Mmegi, Botswana’s only privately-owned daily newspaper. In 2016 he was part of the African investigative reporters that worked on the Panama Papers in collaboration with International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).