Education is a door opener and a life-changer, especially for girls and women, senior United Nations officials stressed at the 56th session of the Commission on Population and Development held last month, amidst a global learning crisis. Sadly, in many parts of Africa, the right to education is not equally accessible to all, especially in terms of gender. Despite progress made over the years, particularly in achieving universal primary education, a significant gender gap in education still persists across the continent.

A girl in her home in Sakoungou, in Southern Central African Republic, on March 11, 2022. Photo: Barbara DEBOUT/AFP

The gender gap in education across Africa remains a significant challenge. Despite progress made towards achieving the Education For All (EFA) goals, gender parity in education has not been fully realised on the continent. In fact, as of 2015, only the Seychelles has achieved education for all, and in the same year, over 31 million primary school-age children were out of school in the region, with 53% of them being girls.

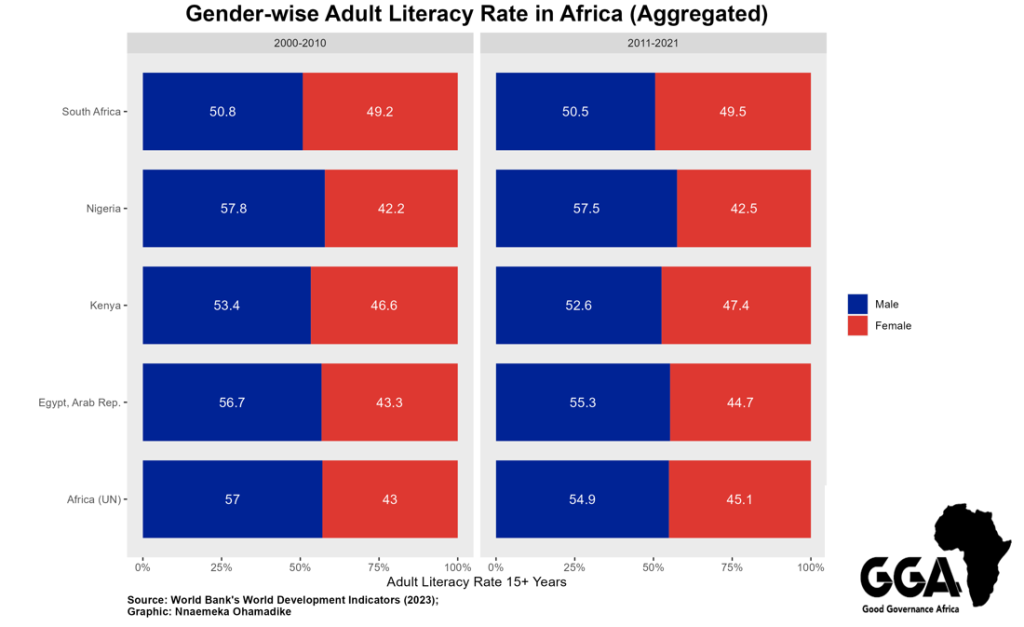

The accompanying figure highlights the persistent gender disparities in adult literacy rates in Africa, despite the progress made over the two decades since the signing of the Millennium Declaration. While efforts have been made to improve literacy rates, gender inequality in access to education and literacy remains a challenge.

Globally, there are 118.5 million girls who are out of school, with women accounting for almost two-thirds of all adults unable to read. While improvements have been made in some areas, large gender gaps still exist in education, often at the expense of girls, although in some regions, boys are also at a disadvantage.

The disparities extend beyond literacy rates to academic achievement and completion rates. In sub-Saharan Africa, girls face significant challenges, experiencing lower academic performance, lower completion rates in upper secondary education, and higher dropout rates due to various sociocultural factors such as poverty, early marriages, and pregnancies. These factors have historically prioritised girls’ domestic responsibilities and early family life, often overshadowing the importance of their education. Moreover, limited access to quality education and prevailing cultural attitudes towards gender roles further exacerbate the gender gap in education. These barriers deprive girls of essential education and economic opportunities.

A study by the World Bank shows that while other regions of the world are reducing their out-of-school numbers, the number of girls out-of-school in sub-Saharan Africa is now increasing. The gender gap in learning outcomes and enrollment rates in sub-Saharan Africa is particularly pronounced in secondary and tertiary education, and especially so in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects. This disparity is of significant concern considering the growing global skills gap, mismatch, and shortage.

The gender gap in education in Africa is a complex and persistent issue, deeply rooted in long-standing social and cultural norms. Addressing this gap requires a comprehensive and sustained approach to bring about meaningful change. Although many African governments have adopted frameworks and policies aimed at closing the gender gap, the effective implementation of such policies has been a challenge. This is why concerted efforts are needed from governments, civil society, and international organisations to address the gender gap in African education.

Fortunately, successful programmes aimed at addressing the gender gap in African education provide valuable lessons for future interventions. These programmes, for instance, recognise the need to address deep-rooted attitudes about and behaviour toward women, which is a crucial step towards creating a conducive environment for girls and young women to access quality education.

One such programme is the FAWE Gender-Responsive Pedagogy Initiative, which trains teachers to use teaching methods that promote gender equality and empower girls in the classroom. The programme recognises that changing attitudes and behaviours towards women requires a systematic approach that addresses not just individuals, but also the broader social and cultural norms that shape people’s attitudes. By working towards changing attitudes towards girls’ education, the programme is able to promote gender equality and provide more opportunities for girls to access quality education.

Another crucial element of successful programmes is that they are designed to achieve sustained impact. For example, the African Girls Can Code Initiative seeks to equip girls with coding skills that are relevant to their local contexts, to create a pipeline of young African women who are equipped to pursue careers in the tech sector. By partnering with local organisations and governments, the programme ensures that its impact is sustained beyond the life of the programme itself.

Moreover, effective programs collaborate with women as partners to identify and address pertinent issues, engaging both male and female stakeholders who can serve as effective agents of change. For example, Good Governance Africa’s Girl Child Initiative employs workshops and conferences to, among other things, educate girls about potential opportunities in STEM fields. By partnering with organisations such as the Afrika Tikkun Foundation and the Telkom Foundation, the initiative not only promotes STEM education but also highlights the achievements of women in IT, inspiring and empowering young girls in the process.

Finally, successful programmes incorporate monitoring and evaluation to track progress and provide information that can drive accountability and commitment to goals. For instance, the United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative works with governments and civil society organisations to develop policies and programmes that promote girls’ education. The initiative uses data to track progress and identify areas where more work is needed, providing evidence to policy-makers and practitioners about what works and what needs to be improved. By incorporating monitoring and evaluation into their work, successful programmes are able to hold themselves accountable to their goals and to continuously improve their effectiveness.

Addressing the gender disparities in education must be a top priority development goal for African countries. As the only continent projected to have a positive fertility rate by 2100, Africa has the potential to reap a demographic dividend, but it can only be realised if the right skills and opportunities are provided to girls and women through quality education.

This article first appeared on Mail & Guardian on 20 May 2023

Nnaemeka is adataanalyst andresearcher at Good Governance Africa. He completed hisMastersdegree in e-Science (Data Science) at the University of the Witwatersrand, supported byascholarshipfrom the South African government’s Department of Science and Innovation.Much of his research explores socio-politicalissues likehuman development, governance,disinformation,bias,andpolarisation, usingdata science andAItechniques.He has published research inscholarlyjournalslike Politeia, Journal of Social Development in Africa, and The Africa Governance Papers. He hasexperience working as a Data Consultant atDataEQ Consultingand teaching at the Federal University,Lafia inNigeriaand the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.