Introduction

Since Zambia’s independence in 1964, the country has experienced several successful changes in leadership, and peaceful transfers of power. However, there have been instances of political violence and points of instability. Zambians are preparing to head to the polls, which are predicted to be a tight contest between the opposition candidate, Hakainde Hichilema (UPND), and the incumbent President Edgar Lungu (PF). Because of COVID-19 precautions, no official rallies or mass gatherings have been permitted, which may put the opposition parties on an unequal footing. The vote will mostly likely be fought around economic issues. Zambia’s anticipated GDP growth this year is 0.6%, after a 3.5% contraction last year, among the worst on the continent. Zambia may be characterised as having relatively high levels of trust deficit, increasing repression, and growing questions around whether the election process will be free fair and credible.

Election contenders

- The Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ) approved 16 presidential candidates to participate in the 2021 general election. The main opposition candidate is Hakainde Hichilema of the UPND. Other notable contenders include Anglican bishop Trevor Mwamba (United National Independence Party), award-winning journalist Fred M’membe (Socialist Party), former Information Minister Chishimba Kambwili (National Democratic Congress Party), and former vice-president Nevers Mumba (Movement for Multiparty Democracy).

- Hakainde Hichilema, contesting for the sixth time, narrowly lost the last election, obtaining 47.6% of the vote. After the last elections in 2016, Hichilema was imprisoned for four months. Initially he was charged for a traffic violation, which later became a more serious charge of treason.

Political violence and campaign restrictions

- In June 2021, the electoral board suspended election rallies due to the surge in COVID-19 cases, but previous elections indicate a pattern of unfair treatment of election campaigning by President Lungu’s government and ECZ.

- Political violence has increased dramatically over the past five years. More recently, the military was deployed after ruling PF party supporters were killed by attackers suspected to be aligned to the UPND in Kanyama. Since then, the UPND has been banned from holding election rallies, and has claimed that Danny Chingangu, a victim of the killings, was in fact one of their party members and not from the PF.

- In the absence of physical gatherings, opposition parties have taken their campaigning to social media to rally their supporters.

Economic crisis

- Zambia’s total publicly guaranteed debt constituted 104% of GDP, around $12 billion, almost 80% of the country’s GDP being in external debt. The country recently defaulted on paying a Eurobond to the tune of $42.5 billion.

- In 2020, inflation rose to 17.4% and remained above the targeted 6-8% range. In the same period, the country’s real GDP contracted by almost 5%.

- The government’s shift towards Chinese financing has compounded its debt problem, and concerns over corruption and lack of transparency in these loan deals have been increasingly apparent.

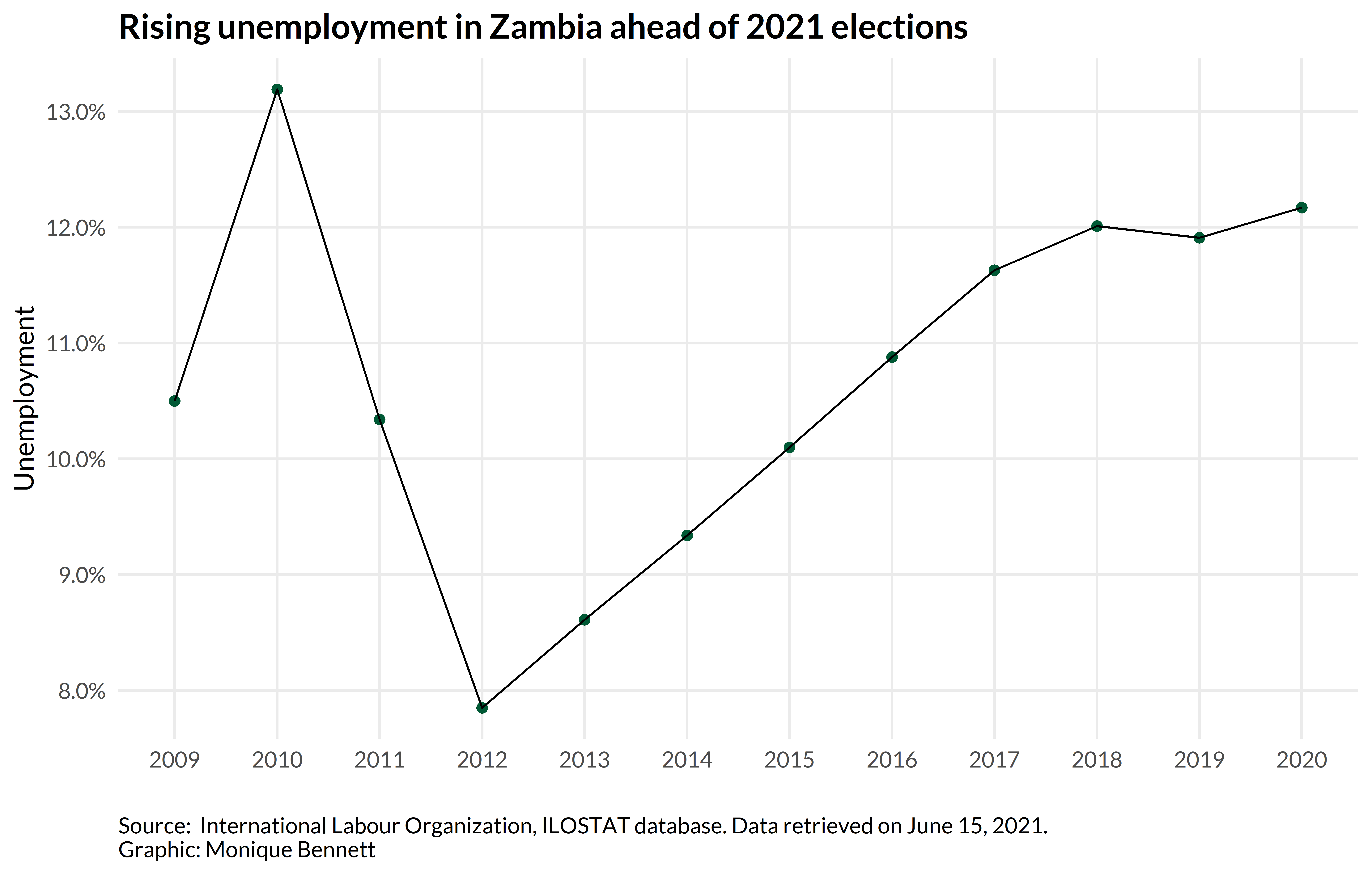

- The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that unemployment rose to 12.17% in 2020, the highest since the PF took office in 2011.

- Youth unemployment is also high. One in five young people are without a job.

- The cost of living has also increased rapidly.

- Zambia owes more than $12bn (£8.6bn) to foreign lenders, resulting in the government spending at least 30% of its revenue on interest payments, according to credit ratings firm S&P Global.

Citizen sentiment

- Recent citizen surveys indicate growing discontent with President Lungu and the progress of the country’s democracy overall. The president’s approval rating declined to 46% and just 37% of citizens were satisfied with the way democracy was working in the country.

- Poverty has risen sharply, with 74% of Zambians indicating that they frequently go without basic life necessities.

Internet shutdown

- Rumours of an internet shutdown during the elections spread over the past week, but have since been deemed false by the government. A statement from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Services said that the information was false and intended to cause alarm.

International election observer participation

- The African Union (AU) accepted an invitation to deploy a short-term observer mission for election day. The mission leader is Dr Ernest Bai Koroma, former president of the Republic of Sierra Leone.

- The European Union Election Observer Mission (EU-COM) was the first international body to respond to the invitation to observe Zambia’s elections. The EU-COM sent 32 long-term observers to Zambia’s 10 provinces, along with 11 analysts based in Lusaka. The mission will be led by chief observer Maria Arena, a member of the European Parliament from Belgium.

- The Commonwealth Secretary-General has sent 14 observers since late July to observe both the pre-election, election preparation and the election day. The group will be led by former president of Tanzania, Dr Jakaya Kikwete.

- The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) agreed to deploy a short-term observer mission, and will include observers from Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Kenya, Libya, Malawi, Rwanda, Sudan, Somalia and Zimbabwe, as well as the COMESA Secretariat staff. Ambassador Ashraf Gamal Rashed of Egypt, with the assistance of Madam Hope Kivengere of Uganda, will lead the mission. The Secretariat has observed the pre-election environment, as it is based in Lusaka.

- On 6 August, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) stated that it would not deploy the SADC Electoral Observer Mission (SEOM) due to concerns over the COVID-19 pandemic. The organisation has had virtual consultations with the ECZ, political parties, academics, and non-governmental organisations. Consultations will continue during the pre-election, election and post-election phases, which conclude on 14 August 2021.

- During these consultations, the SADC has learnt of and expressed regret over reports of sporadic acts of political violence in some areas of Zambia that resulted in the loss of lives. It has called upon political party leaders to guide their supporters towards mutual political tolerance, calm and a peaceful settlement of political disputes.