|

Uganda’s General Election Quick Facts |

|

o 14 January 2021

o 18.1 million people have registered to vote

o 11 presidential candidates

o One female presidential candidate

o President Yoweri Museveni has served 5 elected terms

o 50% plus 1 vote needed for a candidate to avoid a run-off election

o 529 MPs will also be elected

|

Source: Uganda Electoral Commission 2021

Introduction

After a year of several contested elections, the first election of 2021 on the continent takes place in Uganda. Incumbent President Yoweri Museveni is entering his 35th year in power and is the fourth longest-ruling head of state in Africa. The 76-year-old is hoping to get a new mandate for his 6th term as leader of Uganda and the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM). Museveni assumed power on the back of an armed uprising in 1986 and has defied the political laws of gravity which have seen other long-serving leaders removed from office.

Museveni’s rule, though controversial, has seen extended periods of peace and significant developmental changes. However, these positive developments have been accompanied by strong armed tactics to maintain his grip on power through various means such as nurturing a personality cult, employing patronage, compromising independent institutions and sidelining and silencing opponents.

Uganda heads to the polls on the 14th of January for what has already been described by the leading opposition presidential candidate Robert Kyagulanyi, better known as Bobi Wine, as a “war and battlefield”. This has led to growing fears that the election results may lead to an outbreak of violence in the post-election period.

Election Contenders

There are 11 presidential candidates who were approved by Uganda’s Electoral Commission to participate in the 2021 general election. The NRM’s main political contender is the National Unity Platform (NUP) led by Bobi Wine. An interesting development in the election run–up is Dr Kizza Besigye, who has run several election campaigns against Museveni, choosing to opt out of the election race and instead, to ally himself with Bobi Wine to help him gain more support.

Young Electorate Age

Uganda has one of the world’s youngest populations, with about 75% under the age of 30. Both the incumbent and Bobi Wine are hoping to appeal to this young generation of voters. As this young voter pool is becoming more politically aware, the race to capture their vote has been intensifying. Young opposition supporters have become increasingly active and present in the political landscape due to improved media access and travel. The youth vote will be critical for the outcome of the election. Will they remain satisfied with the current political status quo or will they seek a new political order?

Posters of Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni, who is running for his 6th presidential term are seen on a wall in Kampala, Uganda, on January 4, 2021. Uganda gears up for presidential elections which is scheduled to take place on January 14, 2021, as President Museveni seeks to continue his 35-year rule. Photo SUMY SADURNI / AFP

Outbreaks of Violence

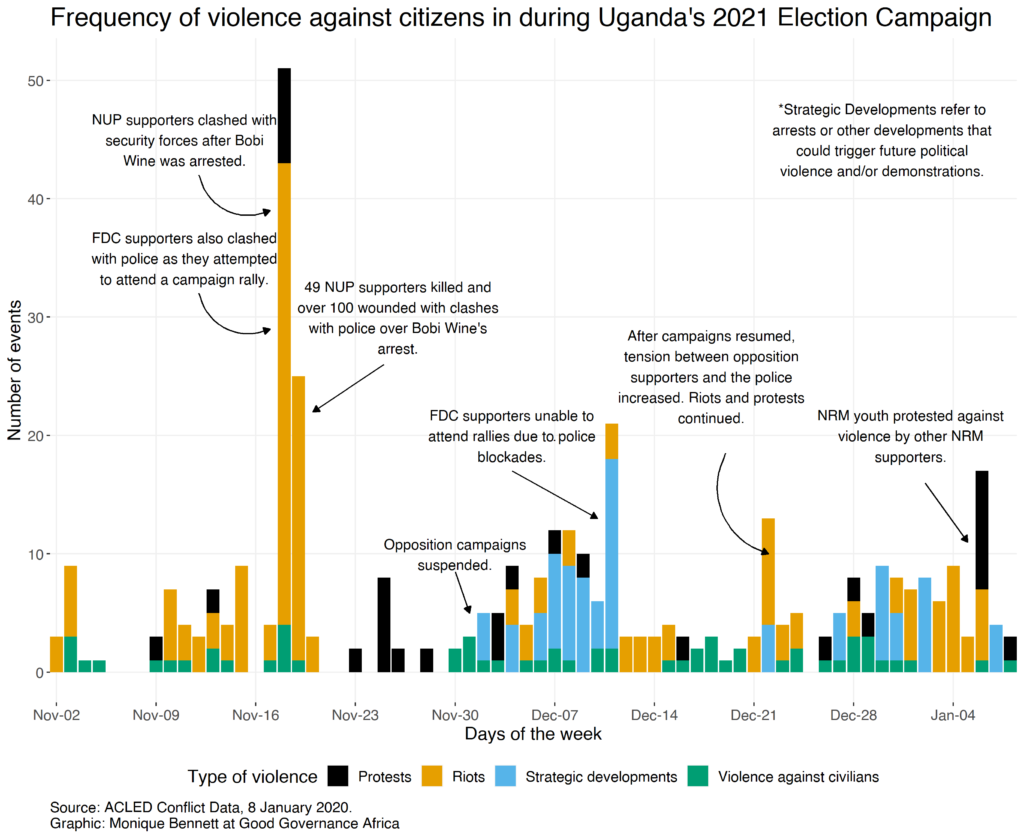

Since the start of campaigning in 2020, nearly 100 incidents of violence have been reportedbetween security forces and citizens, with the month of November registering several incidents such as:

Using ACLED’s conflict data we took a closer look at how the pattern of violence over Uganda’s election campaign played out.

Election Campaigns

Because of the violence meted out to opposition leaders and their supporters in November 2020, several chose to suspend their election campaigns in protest:

All the candidates resumed campaigning later in December, although clashes with government forces continued. To mitigate these campaign struggles, opposition leadership decided to join forces and sign a declaration that would promise collaboration during and after the election. The declaration hopes to ensure unity and cooperation between political players and promote non-violence and constitutionalism in a hostile political climate.

In an attempt to avoid potential voting miscounting of election ballots, opposition political parties and independent presidential candidates have agreed to form a joint tallying centre to compute results from the January 14 polls. As a security measure, they have declined to reveal where the tally centre will be stationed or how it will work. The opposition forces are the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), National Unity Platform, Justice Forum (Jeema), Democratic Party, Alliance for National and Transformation, Renewed Uganda (RU) platform and People’s Government. In a joint statement, the opposition parties resolved to use technology and party structures to collect and relay results from polling stations across the country.

Electoral Commission Impartiality

The Electoral Commission (EC) released provisional election guidelines disallowing mass campaign rallies. Instead, campaigns are to be carried out via broadcast media. Chairperson Justice Simon Byabakama presented a “scientific electoral programme”, which prescribes online registration, virtual campaigns and several other events in line with guidelines in the fight against the coronavirus. Opposition parties expressed concern over this proposed election campaign programme, contending that candidates would not get equal access to media coverage.

Limitations of the EC’s impartiality has been witnesses with the unresponsiveness to the abuses of security forces against opposition candidates and supporters and a concern that thousands of Northern Ugandans in the village of Apaa may not be able to vote as they’ve been removed as an electoral area.

Incumbency Abuses

The ongoing campaign disruption and violence at opposition rallies has been a clear strategy by the incumbent seeking to undermine the election campaigns of his opponents. He misused his office to spread fear amongst opposition candidates and potential voters by unleashing the security forces when he saw fit. Museveni’s rallies have gone untouched by security forces, and few disruptions have taken place despite his large crowds. The Human Rights Watch expressed concern over the violence, and pointed out that NRM rallies carried on as usual whilst the opposition rallies were unfairly disrupted. Moreover, the rallies were held in contravention of provisional election guidelines released by the Electoral Commission disallowing mass campaign rallies. Opposition parties have expressed concern over this so-called “scientific electoral programme”, contending that candidates would not get equal access to media coverage.

COVID-19 Restrictions

The COVID-19 pandemic has been relatively well managed by Museveni’s administration. With under 300 deaths, many Ugandans seem satisfied with efforts to curb the COVID-19 pandemic. As part of the government’s pandemic efforts, radios, televisions, money and food have been provided to citizens. It could be argued that these donations could be part of the government’s election strategy to increase its vote count.

Museveni’s government has imposed COVID-19 restrictions which have given him an advantage in supressing opposition campaigning. If the pandemic numbers are accurate, Museveni’s government has been successful at containing the virus, which may prove beneficial to his election efforts on the voting day.

Restricting Media Freedoms

A recent Afrobarometer survey concluded that a media-only election campaign would likely leave many Ugandans poorly informed, because the level of access to various channels of media remains low, and concentrated among young, more educated men in the urban centres.The survey also found only half of Ugandans think the EC is impartial, and fewer think of it as trustworthy.

In December 2020, the government revoked media accreditation for all foreign journalists, including those already registered to cover the election. Journalists have been requested to reapply for registration within seven days and told that this is to “ensure the industry is well-monitored and sanitized from quacks“. Journalist David Kalinaki of the Nation Media Group said: “the timing is very suspicious, both in terms of when it has been announced, and how much time has been given for conformity.”

Some foreign journalists attached to CBC News, a Canadian public broadcaster, who were already in the country to cover the election, have been deported. Mr Jacob Siminyu, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, has declined to explain why the Canadian journalists were deported.

Election Observers Participation

The European Union has decided not to send their international observers to Uganda, as their recommendations during the 2016 election were not taken into consideration or implemented. Some of the recommendations included reforms to make the Electoral Commission body more independent, eliminate excessive use of force by the security forces, and increase transparency in tallying of votes. For the first time since the 2006 elections, the European Union Election Observation Mission will not have an election observer team deployed. Initially they claimed their non-deployment was due to the COVID-19 pandemic threat and ensuing travel complications, but it soon became apparent that Uganda’s non-adherence to previous election observation report recommendations appears to be the main issue. The EU sent a large number of election observers to Uganda for the 2006, 2011 and 2016 elections. This time, however, the EU delegation has written to the EC seeking to have a list of diplomats accredited to participate in an Election Watch Exercise on the polling days.

The major difference between a diplomatic election watch exercise and an election observer team is the length of observation and mandate. An election observer team usually involves months of observation of the electoral processes, the media coverage of elections, the campaigning of candidates, and the behaviour of security forces towards participating candidates prior and during the Election Day. In short, an election observer team is more beneficial to the tracking of the election processes.

Also, the British High Commission has sought clearance for 46 election observers to be accredited to observe the election period.

The East African Community (EAC) has indicated they will be deploying election observers to the country in two phases – in December and January. The December deployment will be followed by a short-term mission in mid-January.

Lastly, In November 2021, South Africa’s Minister of International Relations and Cooperation offered to work with Ugandan diplomats to assist in election cooperation and share “best practices” to assist their upcoming election process.