Introduction

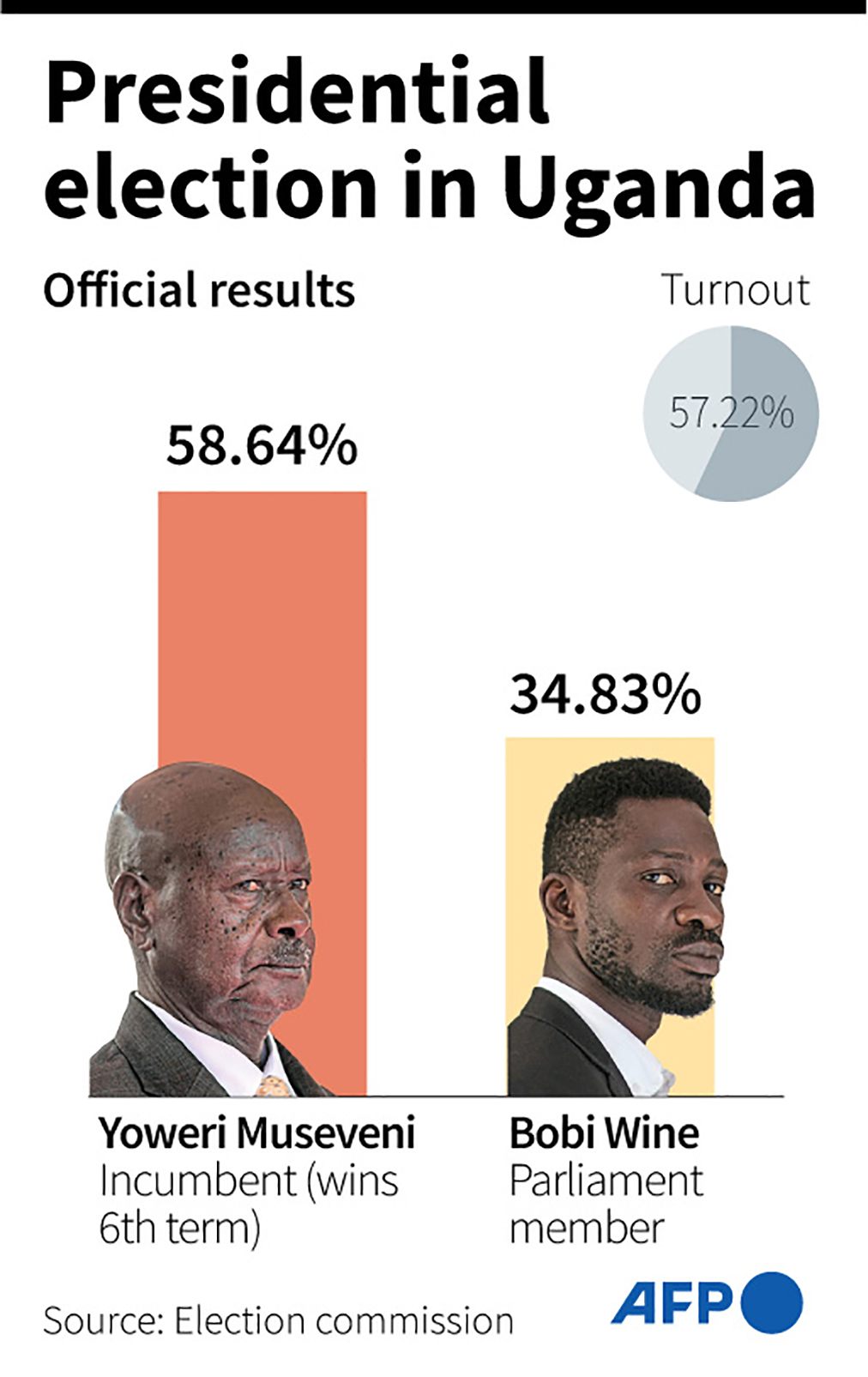

On Saturday 16 January 2021, the Electoral Commission of Uganda (EC) once again declared President Yoweri Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM) as the winners. He will start his 6th term as president of Uganda. Museveni is entering his 35th year in power and is the fourth longest-ruling head of state in Africa. Museveni won 5.85 million votes (58.6%), while the main opposition contender Robert Kyagulanyi, better known as Bobi Wine, won 3.475 million votes (34.8%). Museveni assumed power on the back of an armed uprising in 1986 and has defied the political laws of gravity which have seen other long-serving leaders removed from office.

Museveni’s rule, though controversial, has seen extended periods of peace and significant developmental changes. However, these positive developments have been accompanied by strong armed tactics to maintain his grip on power through various means such as nurturing a personality cult, employing patronage, compromising independent institutions and side-lining and silencing opponents.

After the results were announced, Bobi Wine, leading presidential candidate for the National Unity Platform (NUP), said that his party would initiate the relevant processes to challenge the election results. However, he has since been placed under house arrest by the security forces. Since 14 January 2021, access to Bobi Wine has been limited, including for his lawyers or journalists. The US Ambassador Natalie E. Brown was also denied entry to Bobi Wine’s residence after attempting to visit him on 19 January 2021. His lawyers have filed an application in the High Court of Kampala demanding that a public official deliver a valid reason for his detainment. In terms of challenging the election outcome, the law allows for 20 days after the release of the election results to apply to the Supreme Court for a legal remedy.

The campaigning period leading up to Uganda’s 2021 general election saw an unprecedented level of violence meted out by the security forces towards the opposition parties. Also, several opposition members were arbitrarily detained on different occasions, restrictions were imposed on foreign media, international election observation teams were limited, and on the eve of the election, an internet blackout was imposed. 17.5 million internet users were affected by the internet blackout and it cost the economy an estimated US$9 million. Social media remains blocked, while the internet has been restored.

Election day itself was relatively peaceful, with few instances of violence reported. There was agreement between both international and local observers about concerns over the heavy handedness of the state forces during the pre-election period. The East African Community (EAC) election observation mission stated that the election was largely free and fair, but listed some crucial election discrepancies that their team observed, such as the malfunctioning of biometric voter verification machines, internet shutdown and late delivery of voting material.

Dr Fonkam Samuel Azuu, the African Union Head of Mission, condemned the government’s decision to shut down internet during a time he believes was when citizens needed access to information the most.

The Citizens’ Coalition for Electoral Democracy in Uganda also noted that the pre-election period had seen many problems, and believed that many voters were not given the chance to interact with their candidates due to COVID-19, which left them ill informed.

A police officer sits on a car at the gate of the headquarters of National Unity Platform (NUP) in Kampala, Uganda, on January 18, 2021. PHOTO YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP

Implications

Although this election saw violence and civil unrest it cannot be written off as a completely illegitimate process. Local observers believe that election day was relatively well managed, with no significant incidents of rigging or ballot stuffing as some opposition representatives claim. Ugandans, for the most part, were able to exercise their right to vote, and the parliamentary results reveal that democratic processes can result in a change of leadership, in this instance, parliamentary. Bobi Wine’s NUP won 56 parliamentary seats with an opposition majority, while Museveni’s NRM lost 20 seats, including that of his Vice President Edward Sekandi. This development should give the opposition parties some sense of a victory, however small it may be for the moment. The NRM still holds the majority in parliament with nearly 500 seats. The NUP has replaced the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) as the leading opposition party in Uganda.

Voter turnout dropped by 10% from the 2016 election, with just 57% of registered voters coming out in this election. Voter education remained a major issue, as mentioned by local observers, as many civil society organisations and development partners were not given permission to operate prior to election day. Seven million registered voters chose not to vote, some may have feared that violence may break out, and others were poorly informed. The government must strengthen its partnerships with these civil society organisations, to improve voter education and thus voter turnout.

The opposition’s legal challenge to the election results could see the judiciary demonstrate their independence and take the case on its merits, rather than simply cowering to Museveni’s demands and dismissing the opposition’s application. If they rightly demonstrate their independence, it will only be the third time on continent where the judiciary has overturned a presidential election and called for a fresh election. I imagine the opposition is holding on to the idea that it is possible to trust the judiciary to be professional and independent. As this important legal precedent has found a footing in other African courts, it will be prudent to monitor the outcome of this Ugandan legal application, as it may be prove to be indicative of the consolidation of democracy and good governance in Uganda.

Deputy President of Uganda’s opposition National Unity Platform Mathias Mpunga says the party “rejects the announced results of the presidential elections”. Video: AFP

Lessons learned

The 2021 election in Uganda has exposed electoral weakness that should be addressed if future elections are to be declared fair, free and credible. The following are concerns and that require attention in order to strengthen the democratic system and good governance in Uganda:

- Improved Voter Education: Despite the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the EC failed to implement favourable ways of promoting voter education. With such a young population, many of the voters were first time voters or ill-prepared second time voters. Better engagement strategies should be formulated, with the assistance of media, civil society and any other relevant organisation, to achieve a more inclusive and comprehensive approach to improved voter education.

- Delayed Opening of Polling Stations: More effort should be made to ensure all polling stations open at the stipulated time. There were several reports of some polling stations only opening long after 07:00. While others opened on time, there were claims that not all polling stations had all the necessary voting material, or that voting material arrived late. This resulted in avoidable long queues, with some voters leaving the polling stations without casting their vote. The electronic devices are necessary to capture and verify details of voters before they can be issued with ballot papers.

- Failure of Biometric Voter Verification Kits: There were allegations that some of the Biometric Voter Verification (BVV) kits used to identify voters were not operational, with some arguing it was due to the internet shutdown. This exacerbated the issue of late opening of some polling stations.

- Slow Changing Political Landscape: While the opposition may not have won the election, there was some degree of the change in the political landscape, as we saw some candidates who due to their high-ranking positions as incumbent officials or their affiliation to the ruling party, expected to emerge victorious but failed. The election outcome saw several Ministers and the Vice President failing to match their previous election victories. A lesson from this victory for future political candidates is that elections seats are not guaranteed simply due to incumbency.

- Lack of a United Opposition Front/Bloc: There were 11 presidential candidates participating in the 2021 election. The only form of coalition between the opposition leaders was in the election run-up, with Dr Kizza Besigye, who has run several election campaigns against Museveni, choosing to opt out of the election race and instead, to ally himself with Bobi Wine to help him gain more support. This lack of cohesion amongst the opposition saw them challenging each other in multiple constituencies, resulting in splitting the vote of the opposition vote, benefitting the incumbent.

- Establishment of a Joint Tallying Centre: In an attempt to avoid potential miscounting of election ballots, some opposition political parties and independent presidential candidates agreed to form a joint tallying centre (JTC) to compute results from the January 14 polls. As a security measure, they declined to reveal where the JTC would be stationed or how it will operate. The opposition parties resolved to use technology and party structures to collect and relay results from polling stations across the country. This initiative is commendable as it mitigates against potential election counting fraud.

- Electoral Commission Partiality: Incidents of EC’s partiality was on display during these elections. The EC released provisional election guidelines prohibiting mass campaign rallies. Instead, election campaigns were to be carried out via broadcast media. Chairperson Justice Simon Byabakama presented a “scientific electoral programme”, which prescribes online registration, virtual campaigns and several other events in line with guidelines in the fight against the coronavirus. In theory, this is a sound approach in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, in practice, opposition parties expressed concern over this method of campaigning, contending that candidates would not get equal access to media coverage. In addition, further limitations of the EC’s impartiality were noted with the lack of response to the many claims and instances of abuse by the security forces against opposition candidates and supporters. Also, the restriction of some opposition party agents to observe polling stations on the day of voting was of serious concern, and not adequately addressed by the EC.

- Incumbency Abuses: There is an urgent need to find a more systematic approach for all Electoral Commissions on the continent to find ways to stem incumbency abuses. In Uganda, campaign disruptions and violence at opposition rallies was a defined strategy by the incumbent seeking to undermine the success of the opposition’s election campaigns. He allowed the misuse of his office to spread fear amongst opposition candidates and potential voters by unleashing the security forces when he saw fit, while Museveni’s own rallies were untouched by the security forces and held with few disruptions despite drawing large crowds. Moreover, the rallies were held in contravention of provisional election guidelines released by the Electoral Commission disallowing mass campaign rallies.

- International Election Observers: Because of the low number of international election observer teams deployed, some local embassies stationed in Uganda asked for accreditation as diplomatic election watchers rather than fully deployed international election observer teams. The major difference between a diplomatic election watch exercise and an international election observer team is the length of observation and mandate. An international election observer team usually involves months of observation of the electoral processes, the media coverage of elections, the campaigning of candidates, and the behaviour of security forces towards participating candidates prior and during the Election Day. In short, an election observer team is more beneficial to the tracking of the election processes while the diplomatic election watch, due to its composition, tends to focus on the election day process itself.

Additionally, the role of local observers becomes all that more important. As the Malawi case study showed, a more home-grown ownership of the election process can prove successful despite the absence of international election observer teams in these uncertain Covid-19 times.

A balanced and more robust assessment of the 2021 General Elections in Uganda