Climate change: these two words signify a global crisis with consequences for all of us. In Lagos, Africa’s most populous city, the risk of extreme rainfall threatens to increase flooding, destroy infrastructure and displace numerous people. Across the continent, from Malawi’s drought-stricken fields to Mozambique’s battered coastlines and the expanding desertification of the Sahel, climate change is a brutal reality.

The 2015 Paris Agreement was once celebrated as a turning point toward a sustainable future. The agreement is a legally binding treaty that created a framework for countries to commit to limiting warming to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Under the agreement, countries would present self-defined targets and plans; these are not, however, legally binding. The conflict between an international ambition — even a binding treaty — and country-level implementation, driven by national interest, is a classic collective action problem.

Meeting Paris targets?

A critical question is whether countries genuinely live up to their commitments under the Paris Agreement. Scientists have warned that crossing the 1.5°C threshold threatens severe climate impacts. In the meanwhile, the world is on track for 2.7°C warming, with 2024 being the first year to cross the 1.5°C threshold.

At the heart of the Paris Agreement is the requirement for countries to submit nationally determined contributions (NDCs), roadmaps outlining how they intend to reduce emissions and strengthen resilience and adaptation. These NDCs include policies and measures they will adopt for implementation.

The framework ensured they were flexible and country-led, acknowledging the differences in historical responsibility for emissions and the economic capacity of countries to address the issue.

This approach has allowed nations to set unambitious targets and delay meaningful action. An analysis of the initial set of NDCs revealed that seven of the eight highest-emitting countries submitted pledges far weaker than needed to meet equitable allocations in keeping warming under 1.5°C.

Worse, most countries are failing to update their commitments. To date, fewer than 10% of signatories have submitted updated NDCs. This demonstrates the growing mitigation gap: the difference between stated commitments and the reductions required to meet scientifically informed targets.

The developing world

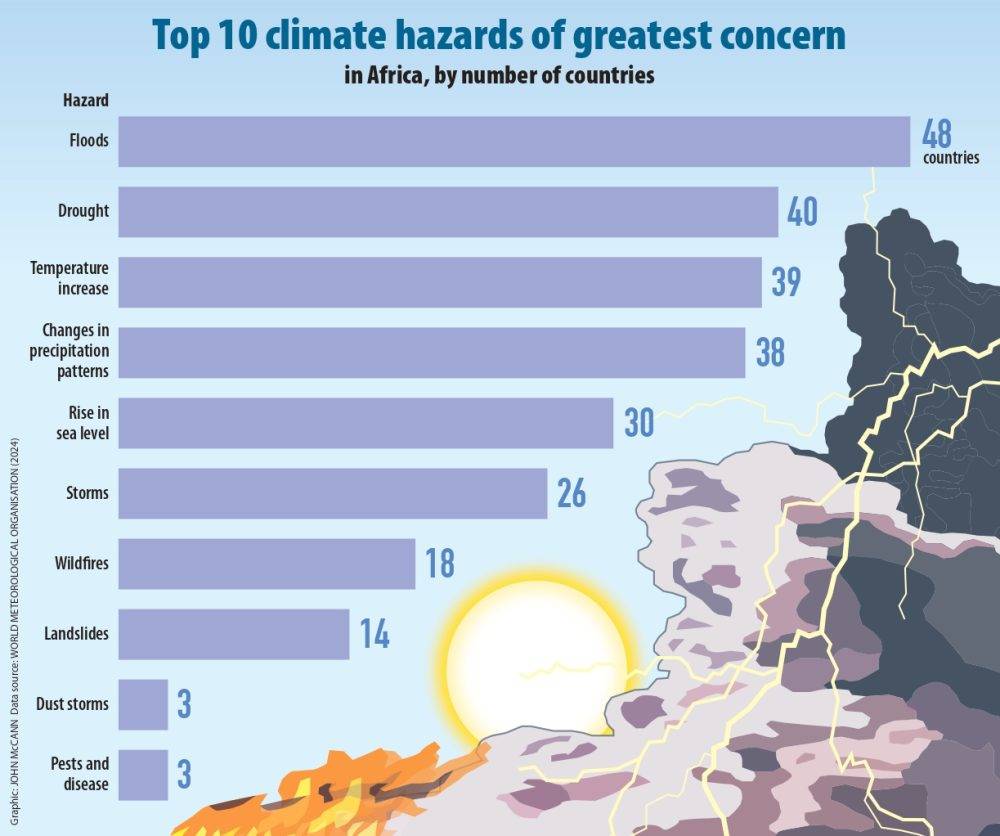

For developing nations, the climate crisis is not limited to emissions reduction; it’s a fight for survival. Most of the world’s population lives in developing countries, which bear the brunt of climate disasters despite historically contributing the least to the problem. African countries have contributed 3.5% to historical emissions.

But countries in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America are facing rising sea levels, devastating heat waves and agricultural collapse. Rising sea levels threaten coastal cities in North and West Africa, including Dakar in Senegal and Alexandria in Egypt. Meanwhile, erratic rainfall and drought have reduced cereal crop production in Tunisia, South Sudan and Ethiopia.

Developing countries have long and rightly pointed out that global climate targets and discussions often ignore historical responsibility and contain an element of hypocrisy. Wealthy countries built their economies on the back of fossil fuels, yet now expect poorer nations to transition without having had the same opportunities for industrial growth.

$100bn elephant in the room

Partially in compensation for this recognised hypocrisy, the Paris Agreement included a $100 billion a year climate finance pledge to support developing economies in reducing emissions and adapting to the unavoidable climate impacts. This promise has been broken.

Developed countries have not met the target. Moreover, instead of the promised grants, climate financing has primarily taken the form of loan-based agreements, threatening to deepen the existing debt crisis facing many developing countries.

Developed countries, such as the United States and the members of the European Union, dictate climate finance and negotiations. Developing countries must adhere to the attached conditionalities to receive a portion of the limited funding.

Moreover, the financing available may not fit the specific situation well. Wealthy nations and the financing mechanisms they put in place prioritise mitigation (reducing emissions) over adaptation (building resilience to navigate mounting climate impacts).

According to the Joint Report on Multilateral Development Banks’ Climate Finance, 67% of the amount allocated to low- and middle-income countries financed mitigation, while 33% financed adaptation. Adaptation is not optional for countries already facing the worst of climate change — it is a necessity. In an environment of limited financial support, several developing countries cannot prepare for the next climate disaster, reducing resilience and exacerbating existing vulnerabilities.

Trump issues

The Paris Agreement’s country-led commitments were meant to foster global cooperation. But the lack of enforcement mechanisms has slowed crucial negotiations and allowed countries to underdeliver on their obligations.

Incentives to prioritise national ambitions won over incentives to cooperate, and there is little in the way of effective deterrence for defection.

This weakness is demonstrated by the US’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. In 2017, president Donald Trump pulled the US out, arguing that the deal imposed an unfair economic burden while allowing major polluters like China and India more leeway.

Although the US later rejoined under president Joe Biden, Trump withdrew the US a second time at the start of his second term under the Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements executive order. This reaffirmed how easily major players can abandon global climate efforts, exposing the agreement’s fundamental instability.

COP30: Credibility at Rio?

The upcoming discussions at COP30, in Brazil in November, will assess the extent to which nations are delivering on their pledges. Early signs strongly suggest a shortfall, with emissions cuts lagging and climate finance gaps continuing to widen.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change faces a moment of reflection and opportunity to restore the credibility of the Paris Agreement.

COP30 should introduce stronger rules to enforce NDC commitments and provide support where needed to help developing countries meet them. To achieve this, the broken system of climate finance must be overhauled.

The long-promised annual $100 billion pledge must finally be met with direct, easily accessible funding for developing nations desperately needing it. This funding will be essential to fill the financing gaps for developing countries and enable countries to implement their latest NDCs.

Additionally, the terms associated with the financing should avoid increasing the debt burden and enhance climate resilience. These terms must not jeopardise energy security or countries’ economic prospects.

COP30 should also prioritise adaptation funding for developing countries. Moreover, the adequate financing and operationalisation of the loss and damage mechanism is crucial. Filling the gap in financing adaptation helps address the hypocrisy related to historical responsibility for climate change.

The Paris Agreement’s ultimate success in meeting its objectives hinges on the ability of countries to move from vague commitments to concrete and equitable burden-sharing.

The struggle to implement the goals of the Paris Agreement demonstrates the conflict between global cooperation and national self-interest.

But sustained failure in addressing the collective problem of climate change will result in devastating consequences. These include increased migration, irreversible destruction of ecosystems, hunger and increasingly fragile economies. COP30 presents an opportunity for a recommitment to the spirit of the Paris Agreement and new global leadership in climate diplomacy.

- This article first appeared in Mail & Guardian.

Vincent Obisie-Orlu is a Natural Resource Governance researcher at Good Governance Africa. He holds a BA in International Relations and Political Studies from the University of the Witwatersrand. His work focuses on natural resource governance of critical minerals, Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) issues, sustainable finance, and energy policy in light of the energy transition.