In mid-February 2025, M23 rebels captured Bukavu, the capital of the eastern DRC’s South Kivu province, with little resistance from government forces. Bukavu is a commercial hub of around 1.3 million people, the fall of which is another significant blow to Kinshasa’s authority at home and in the region.

With Rwanda’s support, M23 resumed armed activity in late 2021, after nearly a decade of dormancy following its defeat by a UN-backed military operation in November 2013. This latest offensive, in which M23 made rapid territorial gains, including the seizure of North Kivu’s capital city Goma last month, seems to have caught both the DRC and international community off guard.

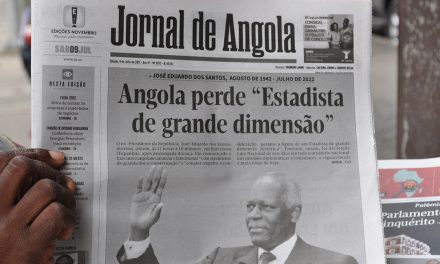

Families wait in a boat with their belongings for departure to Minova from a pirogue dock on the shores of Lake Kivu in Bukavu on February 21, 2025, as around 42,000 people have fled the conflict raging in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo and crossed into Burundi in the past two weeks, the United Nations said. Rwandan-backed M23 fighters have made big gains in the eastern DR Congo, seizing the cities of Goma and Bukavu and stoking fears of a regional conflagration. The UN warned that the M23 “continues to advance towards other strategic areas” in the eastern Congolese provinces of North and South Kivu. (Photo by Luis TATO / AFP)

The coming weeks will likely clarify the scale and shape of Rwanda and M23’s ambitions in the region. M23 has already begun filling administrative positions vacated by fleeing civil servants in North Kivu. Kagame may look to install a friendly administration in Kivu to ensure Rwanda’s security and economic interests, and perhaps even seek a form of annexation at a later date.

M23’s ambitions—whether they extend beyond the Kivus and, as publicly stated, aim for regime change in Kinshasa—remain uncertain. However, the risk of further escalation and regionalization of the conflict is significant, making decisive international action essential.

Rwandan Support for M23

The March 23 Movement has its origins in earlier Rwandan and Ugandan-backed rebel movements of the First (1996-1997) and Second (1998-2003) Congo wars. Corneille Nangaa, head of M23’s political arm, has cited Tshisekedi’s “corrupt rule”, repression of political opposition, and exclusion of DRC’s Tutsi ethnic minority community as the group’s raison d’etre. While elements of these grievances may be legitimate, M23’s actions are inextricably tied to Rwanda’s regional geostrategic ambitions. Recent UN estimates suggest M23’s 6,000-strong force in the eastern DRC is supported by 4,000 Rwandan Defence Force (RDF) troops.

Conflict in eastern DRC is commonly viewed as the result of a scramble for minerals. However, Rwanda’s support for M23 is shaped by economic, political, and national security interests. It is true that eastern DRC is rich in minerals, including gold, tin, tantalum and others which are increasingly valued in global supply chains, particularly the tech industry. In 2023, Rwanda’s largest export was gold ($885 million; 65% of its total exports), despite producing little locally. While it is true that Rwanda can entice Congolese producers to legally and illegally supply gold through lower tariffs and taxes, historically, peaks in Rwandan mineral exports (as a share of total exports) have tended to coincide with Rwandan direct military or proxy occupation in the eastern DRC. A good way to assess the validity of this claim will be to monitor if Rwanda experiences a significant surge in gold, tin, and tantalum exports this year, following recent M23 operations.

From a national security perspective, Rwanda views the presence of the Democratic Forces of the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) – opposed to the RDF rule of Rwanda in the eastern DRC – as a direct threat. Kagami has reiterated how “securing Rwanda’s borders” is critical for the country’s middle-income growth plan ambitions. In a region racked by conflict, Rwanda’s internal stability over the last two decades has been a cornerstone of its economic success. Despite a challenging global economic environment, Rwanda averaged a GDP increase of 8.2% in 2023, with growth across its services (44%), agricultural (27%), and industry (22%) sectors. However, this national economic growth comes at a regional price; proxy groups in the eastern DRC allow Kagame’s government to monitor and supress any Rwandan opposition movements that might use the region as a base for wider political mobilisation against himself and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). This approach has been used by Kagame in Mozambique, where RDF’s presence has coincided with targeted assassinations of Rwandan dissidents in hiding. Without democratic reforms that address issues of blocked political participation and abuse of civil liberties, resulting unrest could undermine the country’s hard-won progress.

Moreover, Rwanda and Uganda, once allies during First and Second Congo Wars, are now rivals that compete for influence in the eastern DRC. Research by the Congo Research Group, for example, argues that the current resurgence of M23 was triggered by this rivalry—in particular, the November 2021 deployment of Ugandan troops under the joint DRC-Uganda Operation Shujaa against the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and the announcement of a large road-building project in 2019 designed to boost trade between Uganda and the DRC. Both developments were viewed by Rwanda as a direct threat to its economic and security ambitions, which jolted them into reactivating M23.

A tepid international response

Rwanda has built an image as a stable, business-friendly environment, with strong public sector management, anti-corruption measures, and policy consistency. This has helped make the country an attractive investment destination and helped it forge strong international partnerships. Rwandan troops are also among the most deployed on the continent within multilateral peacekeeping missions and bilateral arrangements, further extending the country’s sphere of influence. This may partly explain the weak response to the current crisis in the DRC.

Last December, following the UN Group of Experts report on the extent of the RDF’s support to M23, no country on the UN Security Council, including the permanent five, called for actions against Kigali. After last month’s escalation in conflict, the US, France, the UK, and China have explicitly called for the withdrawal of Rwandan forces from the DRC. However, threats to cut foreign aid or impose targeted sanctions on Rwandan officials have not been carried out. The EU is similarly struggling to form a unified diplomatic response to pressure Rwanda into ending support for M23. The EU has a range of actions it could take, including reviewing European financial support for the deployment of 4,000 Rwandan security personnel in Mozambique and revaluation of EU foreign aid and supply chain MoUs. However, while Belgium, Germany, and Sweden are taking a more aggressive stance, other European capitals including Lisbon and Paris seem to prefer a more cautious approach.

Historically, SADC countries have posed a significant obstacle to Rwanda’s geostrategic ambitions. It was Angolan and Zimbabwean forces that prevented Rwandan and Ugandan troops from taking control of Kinshasa and deposing President Laurent-Desire Kabila in 1998. The United Nations Force Intervention Brigade (comprised of South African, Tanzanian, and Malawian forces) were responsible for halting M23’s 2013 campaign in the eastern DRC and forcing the group’s previous leader Sultani Makenga to surrender.

Rwanda now seems to be taking advantage of a weakened SADC which is struggling to coordinate an effective response. Following the deaths of 14 South African National Defence Force (SANDF) soldiers at the hands of M23 in January, SADC held an extraordinary summit which “condemned in the stronger terms the attack on SAMIDRC troops by M23”. However, there was no mention of the material and operational support provided to those troops by Rwanda or condemnation of Kigali’s actions. Between July 2021 and July 2023, both SADC and RDF troops were deployed to the same region of Mozambique under separate agreements (Rwandan forces remain present). The RDF likely had a close view of SADC forces weaknesses, particularly in air and logistics support, and used these insights against them in North Kivu.

On 08 February, SADC and the East African Community (EAC) held a joint summit on the security situation in the eastern DRC. The Joint Summit called for the resumption of direct negotiations with all parties, including M23 (something Tshisekedi has been opposed to) and the merging of the Luanda/Nairobi peace process – both of which favour Rwanda.

At present, the balance of power seems to heavily favour Rwanda, with Kagame maintaining his typically defiant stance against pressure to alter course. However, his position may shift if Rwanda’s international partners implement measures that significantly affect the cost-benefit dynamics of his actions in the DRC.

This article first appeared in Mail & Guardian.