At the time of last year’s local government elections, it appeared we were at the end of a political age in South Africa. Since then, however, little evidence has emerged to suggest that this was, or is, the case. It is November 2022, and the African National Congress (ANC) is a declining force.

For nearly 30 years, the ANC claimed dominant party status as South African national and local politics entirely revolved around the party’s dynamics. While the ruling party remains, by a significant margin, the “largest fish” in South Africa’s political pond, these waters are murkier than ever.

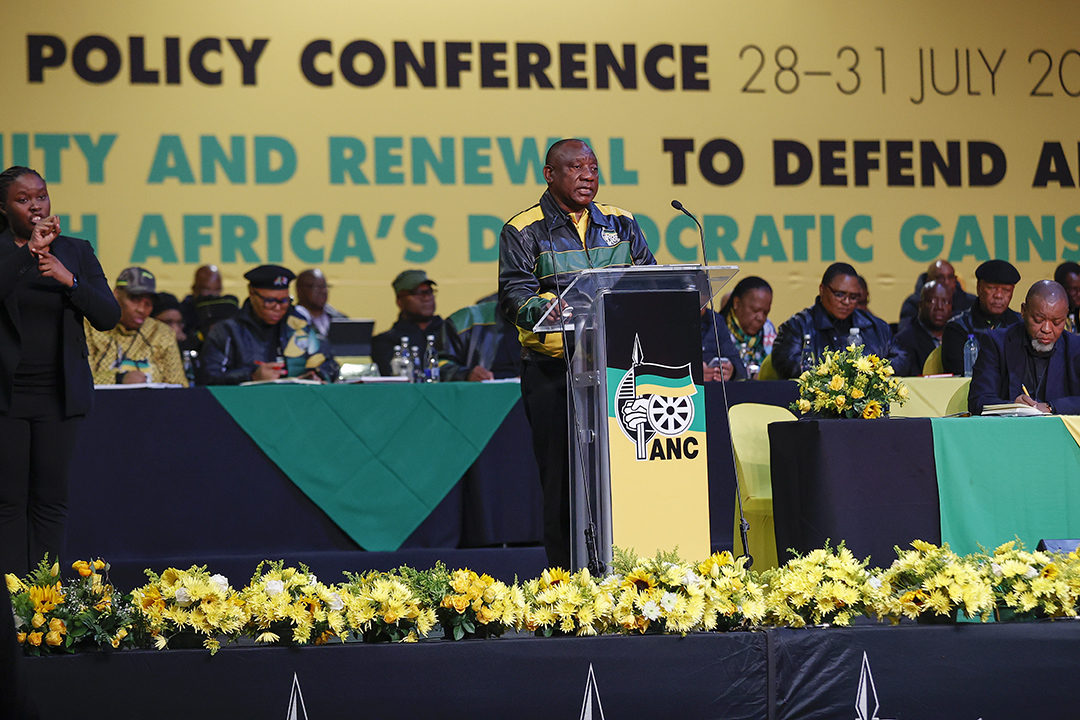

South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa addresses Africa natinal Congress (ANC) delegates at the National Recreation Center (Nasrec) in Johannesburg on July 29, 2022 during the first day of the party’s National Policy Conference. Photo: PHILL MAGAKOE/AFP

One reason for this is that the biggest political gainers in the last five years have not been the main opposition parties, the Democratic Alliance (DA) or the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). Rather, the beneficiaries of the ANC’s decline have been smaller parties built around specific interest groups, which maintain support bases that have distinct geographic patterns.

The ANC’s accelerated decline

Ahead of the ANC’s national elective conference next month, its president, Cyril Ramaphosa, is battling to keep control of his own party. Criticism has been levelled at his leadership at several levels, including from former presidents and sitting ministers.

The ANC itself has yet to recover from the most recent local government elections, when its national vote share dropped below 50% for the very first time. Between the 2011 and 2021 municipal elections alone, the party’s s overall vote share dropped by 16.36%. Moreover, its prospects for maintaining an exclusive national parliamentary majority post-2024 are mixed at best, as it increasingly relies on a rural base.

The extent of these problems would have been difficult to imagine on the eve of the party’s 51st elective conference in 2002. In the run-up to that conference, the party had its share of internal squabbles, featuring familiar names including former President Jacob Zuma, Ramaphosa himself and then President, Thabo Mbeki.

However, back then, these rivalries paled in comparison to the outward unity the ANC projected and the electoral supremacy that it enjoyed. The conference itself was arguably the least fractious in the party’s history, with minimal challenge faced by the incumbent “top 6”, particularly Mbeki.

Contrast that with the forthcoming December 2022 conference, when each position in the executive is contested and the incumbent president’s primary asset is the fact that the largest opposition faction has yet to actually agree on who their favoured candidate is. Such challenges are also historically unusual. Only twice in the last 75 years – in 1952 and 2012 – has an incumbent ANC president seeking a second term faced a contest of this sort.

The 2002 conference was a prelude to the party’s apotheosis at the 2004 national election, when it claimed nearly 70% of the vote. The dominance extended to provincial legislatures as it recorded two-thirds of the vote in every province except KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape.

The ANC bears significant responsibility for its subsequent decline. The role corruption and personality-based factionalism have played in eroding the vast goodwill that the party once enjoyed – and will never truly regain – is well-documented.

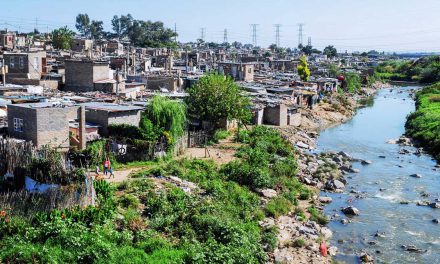

Unemployment, inequality and poverty remain high and maintain the clear racial and gender divides that Apartheid caused. Municipalities continue to fail at high rates, resulting in stagnant living standards, especially among poor families. These problems both contribute to and compound political instability in the country, with July 2021’s wave of riots the clearest example.

Other trends also serve as a harbinger of the ANC’s immediate struggles. Incumbent political parties globally have been punished at the polls since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Inflation and the shock to the international system wrought by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have added to the pressures faced by incumbents.

As an example, of the nine G-20 countries that have held national elections since January 2020, the incumbent leader, party or coalition was defeated in six of them. In the case of two of the incumbents who won, their overall vote share dropped.

Closer to home, long-standing incumbent parties in Malawi, Seychelles and Zambia were defeated in post-pandemic elections. And while the ruling MPLA in Angola prevailed, they too saw a substantial decline in their victory margin.

Regionalisation in our politics

If any factor explains the continued presence of the ANC as the only party capable of sustaining anything resembling a national majority, it is the ephemeral fortunes of the two largest opposition parties, the DA and the EFF.

Following the 2016 municipal elections, it appeared that the two parties posed a meaningful threat to ANC dominance. For the first time in the post-Apartheid era, the vote share gained by the two largest opposition parties had exceeded 35%.

Since then, the DA has regressed, with party leaders – especially those of colour – defecting and party support bleeding to other groups including ActionSA, Good, and the Patriotic Alliance. Notably, these newer parties draw support from specific segments of society and certain regions of the country.

The trajectory of the EFF is more uneven. The party increased its vote share by 2% between the 2016 and 2021 local government elections, but this masks the regression the party experienced in terms of actual votes. In 2021, the EFF received 2,419 million votes for ward council and proportional representation council seats. It had more in 2016: 2,446 million.

The two parties that have most benefited from the struggles of larger parties are Freedom Front Plus (VF Plus) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). Both have improved their electoral performance in both proportional and absolute terms over the last decade.

This revival in the fortunes of two established parties best illustrates the shifting character of politics in South Africa. It signals that “broad church” national politics is in decline as regionally focused and ideologically narrower parties make gains at the expense of the ANC and DA.

Apart from wanting to impede or progress specific policies, neither party desires to grow its national support base. Instead, their preferred model is to gain leverage through direct control of local councils or occupying “kingmaker” status within coalitions in the specific parts of the country which they most care about.

The cost of failure

Should the current parliamentary weighting system of proportional representation remain, then coalition governments will be a core part of South Africa’s political future, especially beyond the 2024 national elections. For such arrangements to work, South Africa’s political parties will need to actively and explicitly prioritise political stability – as they did during our first democratic parliament.

If instead, political parties continue to pursue the marriages of convenience which are all too common in municipalities across the country, then they risk opening up our politics to far more insidious forces.

Large portions of the South African public are already displaying heightened receptiveness to non-democratic solutions. Particularly if such solutions ensure law and order and improve basic service delivery provision.

According to an August 2021 Afrobarometer report, in 2015, roughly one in three South Africans said that they were “very willing” to waive their voting rights if effective government was guaranteed. Within just six years, this had risen to nearly half. Two-thirds displayed at least some willingness to do so.

Given the sacrifices successive generations of South Africans made in securing a democratic future, this is perhaps the most disconcerting trend of all. For now, this cynicism is mainly reflected in the large, mainly younger segment of the country who do not participate in the electoral process. However, the longer it persists, the higher the likelihood that recent commentaries warning about the rise of authoritarianism will prove regrettably prescient.

What happens next?

Both president Ramaphosa, and the party he leads, should manage to stagger through the respective challenges posed by December’s ANC elective conference and the 2024 national elections. In each case, this will have more to do with the lack of an agreed-upon alternative than any true groundswell of support.

Benefitting from a loyal and clearly defined base of support, regionally focused parties such as the IFP and VF Plus will continue to be the main profiteers of this situation, especially at the municipal and provincial levels.

The country’s post-2024 political future is less clear. Over the last year, former president Kgalema Motlanthe has repeatedly posited that while the ANC has diminished, no credible democratic national alternative has yet emerged to take its place. On current evidence, there is not much room to disagree with his assessment.

But until such an alternative emerges, the risk that South Africans will actively look for “cure-alls”, which lie outside of hard-won democratic norms, is considerable.

This article first appeared in the Mail & Guardian.

Pranish Desai is a doctoral student in political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His core areas of focus are in comparative politics and political methodology, with a specific interest in the politics of Southern Africa. Between 2021 and 2024, Pranish held several key positions within the Governance Insights and Analytics programme at GGA. In these roles, he was centrally responsible for the elevation and enhancement of the Governance Performance Index as GGA's flagship governance assessment tool. Before departing GGA, Pranish also played a key role in the development of our strategic framework for the 2024-2028 period.