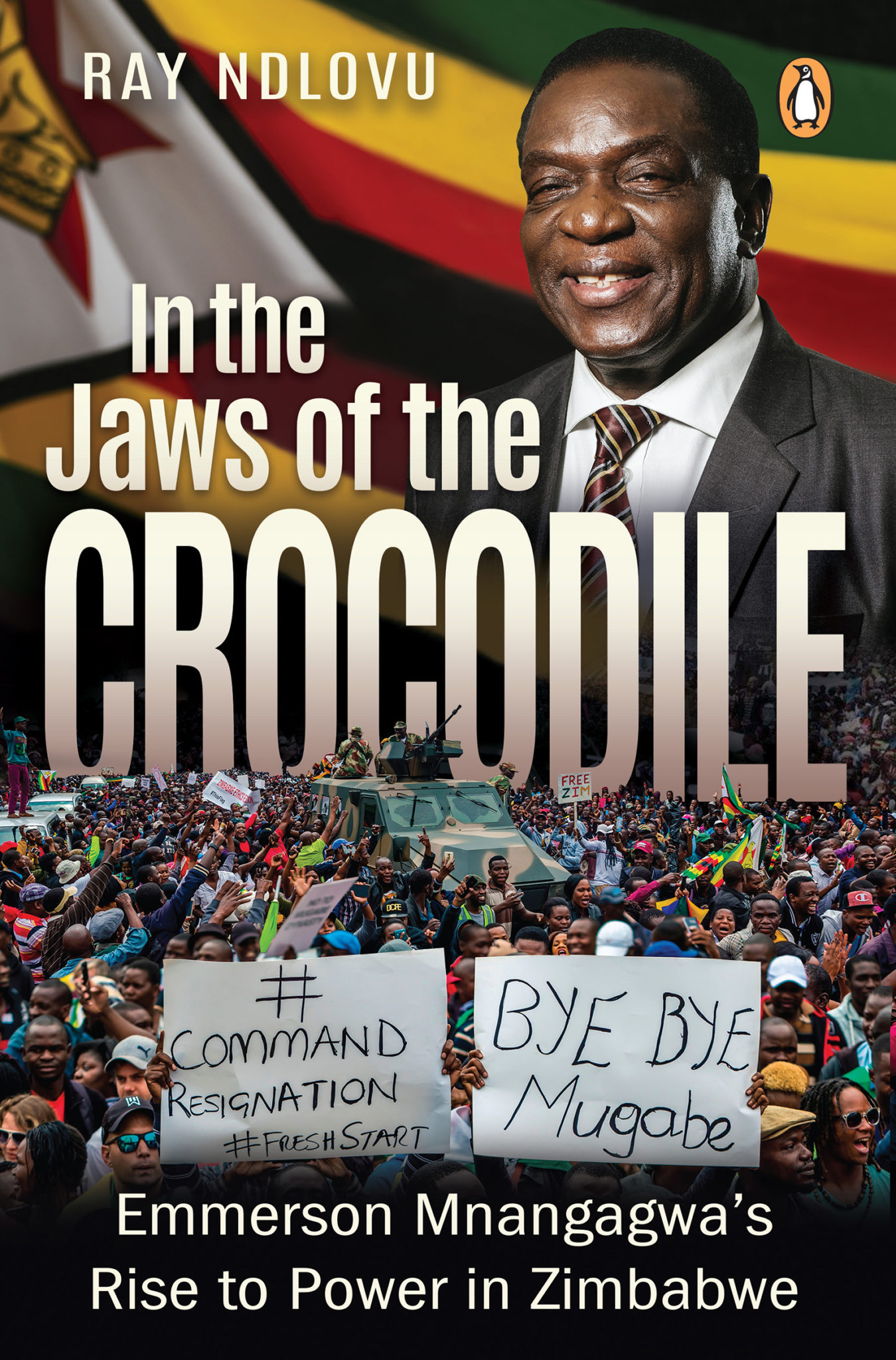

Book review: In the Jaws of the Crocodile: Emmerson Mnangagwa’s Rise to Power in Zimbabwe. By Ray Ndlovu, Penguin Books, 2018

In the Jaws of the Crocodile is an exciting account of the coup that shuffled Robert Mugabe off his throne so that Emmerson Mnangagwa could become president of Zimbabwe.

Reading like a thriller, the book reconstructs events before, during and after the coup, laying bare how power is exercised in Zimbabwe. It is like an African version of John Read’s famous book on the Russian Revolution, a kind of 21 days that shook Zimbabwe.

Reading like a thriller, the book reconstructs events before, during and after the coup, laying bare how power is exercised in Zimbabwe. It is like an African version of John Read’s famous book on the Russian Revolution, a kind of 21 days that shook Zimbabwe.

Author Ray Ndlovu, a Zimbabwean journalist, who writes for South African newspapers Sunday Times and Business Day, has reported on his country for some time, and has developed a network of well-placed sources of information.

His first chapters describe the events that led to the coup. Mugabe’s wife, Grace, had for some time been positioning herself to take power after the expected end of her husband’s reign, to the displeasure of the ruling party’s old guard.

Zanu-PF had become divided into two camps: the old guard, known as the Lacoste faction, was centred around Mnangagwa while Generation 40 (G40), younger members who wanted to dislodge the old guard, had chosen Grace as their leader-puppet, her strings being pulled by then minister Jonathan Moyo and his co-conspirators.

The Lacoste faction was named after the French clothing manufacturer, which has a crocodile for its logo – Mnangagwa is famed for having the cunning and patience of that predator. A few months before his ouster, Mugabe had fired ministers identified with the Lacoste grouping. Mnangagwa had also been poisoned in August 2017, but he survived the attempt to kill him.

At rallies to woo the youth, Grace had been delivering diatribes against the Lacoste faction, and especially Mnangagwa. At one rally she referred to him as a snake whose head needed to be crushed. But at a rally on 4 November 2017 she was booed by a sizeable section of the audience. Mugabe was livid, holding Mnangagwa responsible and declaring that he would fire him. Mugabe demanded that the boo-ers be brought to him – such is Zanu-PF’s expectations of control over its population.

From this point things moved fast – the proverbial 21 days that shook the country. Mnangagwa was indeed fired four days later and, fearing for his life, he fled the country, going to South Africa.

This is when the book comes across as a thriller. Mnangagwa’s attempts to leave his country were a nail-biting affair, and his difficulties are recounted by Ndlovu, who has certainly done his research for this book. Ndlovu reveals the experiences of Mnangagwa’s children, some of who accompanied their father into exile.

Mnangagwa’s ally, army chief Constantino Chiwenga, was in China at the time. A day after his return, on 13 November, flanked by a hundred army officers, he issued a warning to Zanu-PF, telling the party to cease the purge it had begun of the Lacoste faction, to which he clearly belonged. The military was disgusted by Grace Mugabe’s moves to grab power – Mnangagwa was their man, especially after four years as defence minister.

By 14 November the army stepped in, moving tanks onto the streets and confining Mugabe to his house. It announced that criminal elements around Mugabe were being targeted and that its moves were not part of a coup.

By 17 November the war veterans’ leader, Christopher Mutsvangwa, called on Mugabe to step down and for the masses to take to the streets, which they did the next day.

After being stripped of the leadership of Zanu-PF, Mugabe eventually resigned on 21 November, with Mnangagwa returning from South Africa the next day. Three days later, on 24 November, the Crocodile was inaugurated as the new president. Despite the assurances of the military, this was indeed a coup and Mugabe was gone, after 37 years in power.

No force of any significance came to Mugabe’s aid, a fact that embittered him. South Africa’s then president, Jacob Zuma, had spoken to Mugabe just before he stepped down and called for calm, but there were no indications of support for Mugabe remaining in office. Mugabe was especially angry that the Southern African Development Community had not come to his aid, and he blamed a “third hand” for his displacement.

Other countries appear to have taken the changeover in their stride, if not to relish it. The United States is suspected to have known in advance about Mugabe’s removal and the United Kingdom’s top diplomat, Rory Stevens, attended Mnangagwa’s inauguration. China issued a statement saying it was the country’s friend, and was watching. Even the timid and conservative African Union “backtracked and soon welcomed the political transition headed by the military under Chiwenga,” according to Ndlovu.

Perhaps more importantly, the army passed a “covert vote of no confidence” on Mugabe. Ndlovu concludes that no Zimbabwean leader can prevail if he does not have the support of the army.

Clearly, Mnangagwa has their support. He was trained in China and Egypt, and he served as head of intelligence and Mugabe’s right-hand man in Mozambique in the late 1970s. He had strong links with the military wing of Zanu from those days.

According to Ndlovu, war veterans played a large role in dislodging Mugabe. They called into question his liberation credentials by emphasising that he was never a fighter, more an orator. They had decided in 2016 to cease their support after attacks on them by Grace and the G40. The G40 leaders and members of the Zanu-PF Youth League took the military’s place as Mugabe’s henchmen.

Throughout this period, Grace and her cohorts were unrelenting in their attacks on the military leaders and war veterans, and Moyo singled out Chiwenga, belittling him for a lack of education.

With his eye on yet another term, Mugabe tried to restore relations with the military in November 2017, in the midst of the coup, hoping they would help him win elections in 2018. They met, without Grace, and military leaders revealed they believed the text of a Youth League attack on military leaders a few days before had been written by Grace. Months later, she denied it, but their attitude towards her decided the issue.

The satisfying aspect of Ndlovu’s book is that, from the point of view of Mnangagwa, it is a complete story: he is fired, goes into exile, and returns triumphant. The latter chapters are taken up by interviews with the main protagonists: Mugabe and Grace, the exiled Moyo, Mutsvangwa and Mnangagwa.

Ndlovu says Mutsvangwa, the veterans’ leader, was enjoying his last laugh. Asked what went wrong for Mugabe, he said: “Senility, a doting mad wife and an indulgence in spies.”

During Ndlovu’s interview with Mnangagwa, he is respectful of the new president, who is pursuing a relatively benign foreign policy, restoring ties with the UK and taking Zimbabwe back into the Commonwealth, which Mugabe quit in 2003.

Mnangagwa comes across as grounded and magnanimous. He is committed to treating Mugabe well for the rest of his days, and he appears to be a pragmatist, wanting to get his country back on its feet. But all is not well, and Mnangagwa barely escaped an assassination attempt in July 2018.

The penultimate chapter covers the election of August 2018, which Mnangagwa won but under less than perfect circumstances. Seven people were killed in protests against the results. Since then, a shortage of currency has kept the country in crisis mode.

This review is being written as Zimbabwe undergoes a heightening of the crisis. After more than doubling the price of petrol and ensuing mass protests, the military has been used for the first time to quell riots and more than a score of people have been killed. Interestingly, Mnangagwa was out of the country when the protests broke out and Chiwenga, now the vice president, was in charge as acting president.

Mnangagwa’s ties to the military are seemingly being deployed in a horrific manner and though he has promised to rein in what he says are fake military personnel, the question remains whether he can act in defiance of the generals.

Ndlovu’s book is mild in its treatment of his subject. We will have to wait to see if Ndlovu’s uncritical picture of Mnangagwa is justified. The new president, meanwhile, will have to learn that democracy means allowing protests, freedom of speech and free elections.

Yunus Momoniat is a researcher and writer at South African History Online and an occasional political commentator.