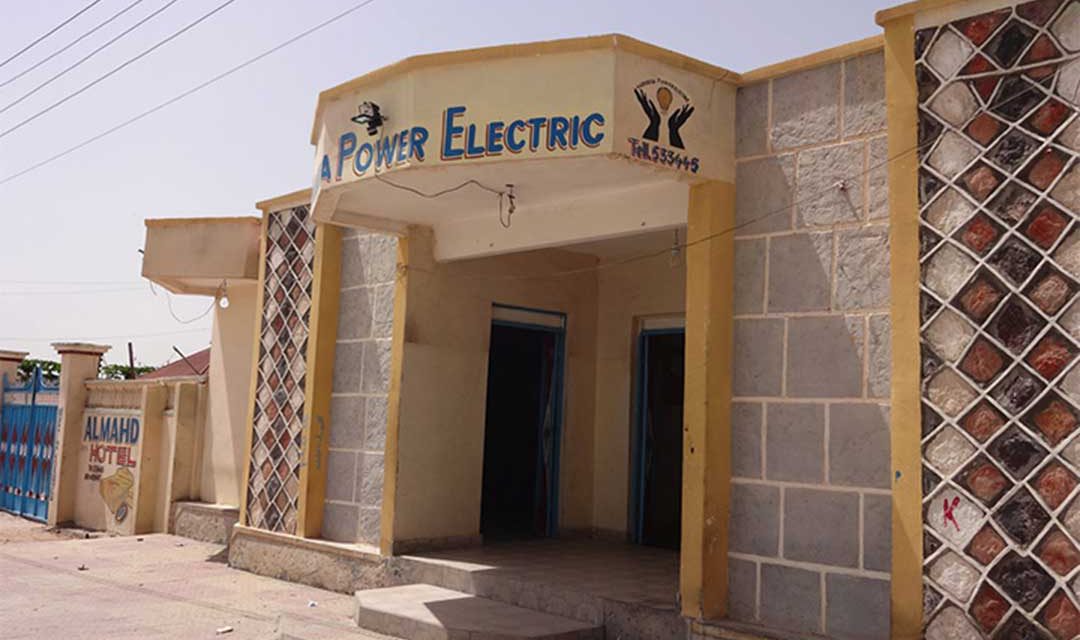

View of Hargeisa, Somaliland Image Emma Lochery.

How informal energy initiatives in the Somali city of Hargeisa are lighting up a once-dark city

The southern periphery of Somaliland’s capital, Hargeisa, is a line of hills offering a panoramic view of the expanding city. One evening in 2014, the owner of an electricity company serving part of the crowded downtown market area climbed up one of the hills, close to the Ambassador Hotel and the airport. The city landscape twinkled and bustled beneath him.

Looking out over the city, the businessman telephoned his head of technical operations and asked him to shut down the diesel generators. Confused, his employee protested that night was approaching, not a good time to turn off the power flowing to thousands of customers in town. The company owner insisted, explaining it was precisely because it was evening that he wanted the machines shut down.

He wanted to see his share of the city turn dark for a moment, marking it out against the city’s expanse of lights.

As he stood on that hilltop, the businessman was in the midst of a negotiation that would put a monetary figure on his contribution to Hargeisa’s landscape of light. One of a dozen power providers serving neighbourhoods across the city, he was merging his company with what was then the largest electricity provider, serving around 30,000 customers on the southern side of the city. He wanted to ensure that, before his generators and distribution grid were converted into shares in a larger company, the valuation of his assets was fair.

Since 2010, such mergers have reshaped electricity provision in Somaliland, creating multi-million dollar companies serving tens of thousands of customers. Despite their growing size and engagement with diaspora investors, donor agencies, and energy consultants from around the world, the roots of these shareholder firms lie in small-scale, informal businesses.

Somaliland’s urban lights are the fruits of two and a half decades of reconstruction since the collapse of the Somali Democratic Republic in 1991. The war in the late 1980s between the Somali National Movement (SNM), the opposition movement based in the north-west of Somalia, and the Siad Barre government in Mogadishu left cities like Hargeisa and Burco in ruins

– government planes had taken off from Hargeisa airport and turned back to bomb the city. Survivors fled to rural areas and then Ethiopia, where refugee camps sheltered over 400,000 people.

The collapse of the Siad Barre government in January 1991 and the descent into civil war among factions in southern Somalia left the SNM in charge of territory in the north west. The clans of what is now Somaliland organised a series of reconciliation conferences – leading to a declaration of independence in May 1991 and the creation of the Republic of Somaliland, though it would take until 1993 to negotiate a more concrete political settlement at a peace conference in the city of Borama.

Aid and investment were scarce. During the 1990s the international community turned a blind eye to Somaliland. Reliant on loans from Djibouti-based business people from Somaliland’s major clan, the Isaaq, the government remained fragmented, under-funded and prone to conflict.

Wartime bombardment and looting had destroyed much of Somaliland’s already degraded infrastructure. In Hargeisa, artillery shells felled electricity poles; wires were stolen and privately owned generators looted for copper. The city’s main electricity plant had been protected and recaptured by the SNM, but the fledgling government had no funds to repair generators or rebuild a grid.

As they returned to the city, people worked hard to rebuild their lives using capital saved from before the war or sent by relatives working abroad. Commerce resumed as people imported food products, building supplies and other essentials, relying on long-standing networks of trade and migration linking northern Somalia to Yemen and the Gulf.

To light their properties and power small businesses, entrepreneurs imported diesel generators. Soon, relatives and neighbours asked for power, and generator owners connected the necessary wires to their diesel engines. The growth of these micro-grids was shaped by localised social connections, but as people realised the commercial viability of electricity provision, they invested in power provision as a business in its own right.

During the 1990s and 2000s, electricity companies developed as offshoots from fuel companies, hotels, cafés and telecommunications companies. At times, generating and selling power became more profitable than the original enterprise.

Equipment was mainly second- hand and distribution networks messy and unplanned. Residents approached companies for power, and companies would “just drag the line and drop it”, explained an engineer working for one private provider.

There were no transformers and lines ran directly from the generators to the customers, causing substantial power loss – up to 40% according to Suleiman Abdullahi Jama, Somaliland’s Director of Energy. Unearthed connections were the norm and unprotected wires liable to be knocked down, a serious problem during the rainy season. Residents referred to the electrical wires above their heads as ‘minada sarae’, ‘the landmine above’.

As Hargeisa continued to develop, these impromptu power providers grew, swallowing weaker competitors and investing in generation capacity. Meanwhile, the government, borrowing money from business people in Djibouti, entered the sector not as a regulator but as a competitor. It partially rebuilt the city’s grid and began supplying customers in 2002, causing consternation amongst private providers.

Power provision, in the words of one company manager, became “a cut-throat business”, with some of the more ruthless suppliers cutting the lines of providers who entered their areas of supply. Clan elders, sheikhs and business people were called in to mediate conflicts and negotiate boundaries between competitors. But by the late 2000s they were warning these solutions were unsustainable, and urged government to drop out of the race and act as a regulator.

Initially, however, the government stayed in business. As the costs of competition mounted, the dozen companies operating around Hargeisa realised their vulnerability. They collaborated to set the price of electricity in the market and present a united front against government intervention. In response to accusations that they were a cartel, the companies said they had to make a profit, but they served the public and deserved recognition and protection. As Mohamed Abdirahman Farah, chairman of Afgal, a private power provider operating in the early 2010s explained, companies were “providing a community service” in the absence of government capacity, and helping to maintain the peace and stability of the country. The companies highlighted their efforts to provide power at a lower rate or free of charge to police stations, courts, mosques, health centres, and nearby streets.

The Somaliland ElectricityAgency Image Emma Lochery

Managers emphasised their support for lower-income households.

“We have been working in this country for so long and we know the situation,” Ismail Hussein, a branch manager at National Fuel Station remarked. “There are a lot of houses that we provide with free electricity, just for charity.”

Nevertheless, tension lingered between companies’ quest for profit and their role in providing essential infrastructure to the public. While cooperation among fragmented suppliers maintained peace in the market, small- scale and poor-quality equipment, coupled with the rising price of diesel fuel, meant that companies charged up to $1 a kilowatt-hour in the early 2010s. To make matters worse, the government electricity agency was on the verge of bankruptcy. This increased pressure on private providers from both government officials and western donors interested in supporting Somaliland’s energy sector to upgrade their service and drop prices.

In response, small companies, looking for a new way of organising themselves, merged into shareholder companies.

In 2009, a company in the south of the city called Kaah Group united with over a dozen smaller electricity companies and hired engineer Abdi Ali Barkhad to build a larger grid.

As the companies’ equipment was unsuitable for an integrated grid, company owners leveraged their diaspora connections to find investors – “those who don’t have machines but cash,” explained Abdi Ali.

Between 2009 and 2011, Kaah combined their generation sites. By 2013 they had over 20km of high-tension wire transmitting power to over 30,000 customers. After further mergers in 2014, they became General Electric.

The mergers that created General Electric brought together small companies, new investors with capital, and engineers with sufficient expertise – and became the model for the power sector in urban Somaliland.

In December 2013, ten companies in northern Hargeisa announced their merger. By 2017, further consolidation had united the two conglomerate companies into a single provider, Sompower.

Other competitors continue to emerge. Across Somaliland’s cities, private electricity providers are consolidating, upgrading their generation and distribution systems and investing in renewable energy.

Challenges remain. Somaliland’s government still lacks serious regulatory power, while the electricity companies’ monopoly power has increased. However, these mergers, and the innovation and activism of the small providers they involve, highlight the power of locally negotiated solutions and the essential contribution locally embedded businesses can make to post- war reconstruction.

Emma Lochery is a political scientist researching business, citizenship, mobility and migration. She has written about the history of Somalis in Kenya and researched life trajectories of African traders in China. Her doctoral work at the University of Oxford examined the politics of service provision, market-making and state formation in Somaliland. She is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Liège, Belgium, studying the politics of employment in Zambia's mining sector.