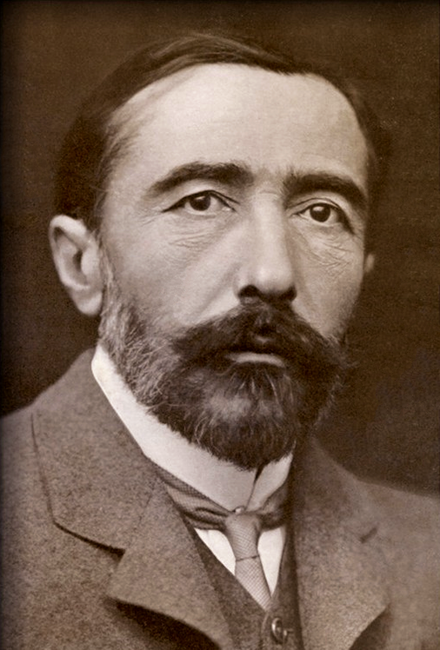

An electronic goods trader follows a televised debate on charges faced by Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta at the Hague-based International Criminal Court (ICC) being dropped, on television sets displayed in an electronics shop on December 5, 2014 in the Kenyan capital Nairobi. The ICC’s Chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, dropped crimes against humanity charges against the president dealing a blow to the tribunal after a long-running and troubled case. AFP PHOTO/Tony KARUMBA

TONY KARUMBA / AFP

Some 122 states have ratified the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2002, among them 34 African countries. However, two cases against current African leaders have focused attention on growing criticism that the court has an apparently exclusive focus on Africa. In one case, in March 2011, the ICC charged Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta for instigating election violence in 2007. The court dropped the charges in December 2014 when the prosecutor and judges accused the Kenyan government of failing to cooperate with it in good faith. In the other case the court issued an arrest warrant in 2009, and again in 2010, for the Sudanese president, Omar al-Bashir, on charges of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. However, it has since failed to detain him for trial. Last June, he was allowed to leave South Africa, a signatory to the Rome Statute, hours before the country’s High Court ordered his arrest.

While still facing the prospect of trial in The Hague, in October 2013 Mr Kenyatta attacked the ICC in a speech to the African Union (AU), saying the ICC had become “a toy of declining imperial powers”. Mr Bashir, in a 2009 interview, said that the ICC was a “tool to terrorise countries that the West think are disobedient”. And the ANC, South Africa’s ruling party, in a statement on the day Mr Bashir was allowed to abscond from the country, said that the ICC was “no longer useful for the purposes for which it was intended”. African opposition to the ICC is coalescing around the argument that the court represents the interests of other countries. “The ICC’s sharpest critics claim that international criminal law does not apply to the powerful, only the weak—hence the focus on Africa, the new court’s ‘laboratory’,” writes Terence McNamee in a 2014 discussion paper on “The ICC and Africa”, published by the Johannesburg-based Brenthurst Foundation.

But the ICC prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, argues that most of the cases the court is trying were referred to it by African countries. “These referrals are basically the countries requesting the ICC to intervene,” she said in a recent BBC interview, adding that the debate about the ICC’s focus on Africa deflected attention from the fact that each of the cases it was trying involved victims. Meanwhile, the AU has moved to extend the jurisdiction of existing courts on the continent to try people accused of serious international crimes. “Expanding the mandate of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights … would help us promote finding African solutions to African problems,” the South African president, Jacob Zuma told the National Assembly last year. Other moves in this direction include the establishment by Uganda and Kenya — both members of the AU — of international crimes divisions of their High Courts, says Mr MacNamee.

In June 2014 the AU extended the African Court’s jurisdiction to include individual liability for serious crimes committed in violation of international law — while at the same time excluding sitting heads of state and senior government officials from the court’s jurisdiction. Given these African challenges to its credibility and jurisdiction, can the ICC establish itself as an undisputed world court? One view is that the ICC simply needs more time to establish itself, Jacqueline McAllister argues in an August 2015 article in Foreign Affairs. In her view, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) established in 1993 — now shutting down — is an example. Though it had no police powers and operated in active war zones, it eventually secured the arrests of the region’s most notorious leaders — Radovan Karadzic, a Serbian politician, and Ratko Mladic and Zdravko Tolimir, two Bosnian Serb military commanders.

They were charged with a range of crimes, including genocide and crimes against humanity. In 2012 Mr Tolimir was sentenced to life imprisonment, which was confirmed in 2015. The trials of the other two accused continue. Some commentators argue that the ICC must demonstrate success in bringing non-African perpetrators of serious crimes to trial and in achieving convictions against them. The court is conducting preliminary examinations in a number of situations outside of Africa, including war crimes and other abuses allegedly committed by the Taliban in Afghanistan, as well as the alleged torture or ill-treatment of conflict-related detainees by US armed forces there in the period between 2003 and 2008. Similar investigations are ongoing in Georgia, Guinea, Columbia and Honduras.

The prosecutor has also reopened the preliminary examination of the responsibility of UK officials for war crimes involving systematic detainee abuse in Iraq from 2003 until 2008. Similar investigations are ongoing in Georgia, Guinea, Columbia and Honduras. The prosecutor has also reopened the preliminary examination of the responsibility of UK officials for war crimes involving systematic detainee abuse in Iraq from 2003 until 2008. Whether these investigations will make it to trial is an open question. “Each case stands on its own legal merits,” says Professor David Crane, Chief prososecutor of the Special Court for Sierra Leone from April 2002 until July 2005. In cases where a suspected serious international criminal is a citizen of a country that is not a signatory of the Rome Statute, the court must obtain a referral from the UN Security Council. But if it were to seek to indict Syria’s president, Bashar al-Assad, for instance, it would be dependent on the politics of the permanent, veto-wielding powers, such as Mr Assad’s Russian and Chinese allies.

“The ICC is often blamed for practice that is really a result of Security Council action or lack thereof,” says Elise Keppler, associate director of the International Justice Program at Human Rights Watch. Other commentators argue that the ICC will only be able to bring its power to bear on African, and indeed other perpetrators of serious crimes around the world, if it is given the ability to sanction member states. “There must be defined repercussions for states that refuse to cooperate with the ICC’s requests,” writes Gwen P Barnes in a 2011 article in the Fordham International Law Journal. To be more effective, the ICC would need to amend the Rome Statute to make it possible to suspend or, in extreme cases, expel member states when they fail to cooperate with the court, Ms Barnes argues. These measures would likely cause the member states to think twice before breaching the Rome Statute, she writes. But Niels Blokker, a professor of international institutional law at Leiden University thinks the proposal is unrealistic.

“Amending the statute is a very complex procedure. It’s a logical thought that countries that do not comply should be thrown out, but what would that achieve? The whole purpose of the Rome Statute is to fight against impunity. For this to happen, you need to be able to continue the dialogue with countries, and you won’t achieve this by suspending or expelling them.” Every international organisation struggles with members who don’t comply with the rules, says Professor Blokker. “It’s the big dilemma of international cooperation. At the United Nations there is the possibility to suspend or expel members, but this has never been done. When you do this, you take away your influence over the country. In the end, it’s not the ICC that should discipline countries that don’t comply. The member states will have to discipline each other.” Meanwhile, some critics argue that the African move to put suspects of serious international crimes on trial on the continent is not without its problems.

International legal and human rights NGO Avocats Sans Frontières (Lawyers without Borders) says that the move may be “a technical manoeuvre to oust the jurisdiction of the ICC”. A wider mandate for the African Court is likely to result in competing jurisdictions and a duplication of the work of the ICC, it argues in a July 2012 paper. The AU’s insistence on excluding sitting heads of state from the jurisdiction of the African Court has also been severely criticised. At the time about 140 African civil society organisations and international organisations signed a declaration against it. “The AU is obligated to ensure that accountability mechanisms have a basis to succeed and [to ensure that the court’s jurisdiction is not used] as a subterfuge for a political agenda,” Professor Crane says. “No one is above the law, not even the ‘good old boys club’ of African leaders.”

In the meantime, the ICC continues to deal with current cases, including this year’s trials of Bosco Ntaganda, accused of war crimes in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Laurent Gbagbo, a former president of Côte d’Ivoire accused of crimes against humanity. It recently showed its teeth by putting Congolese politician Jean-Pierre Bemba, his lawyer and three others on trial for “corruptly influencing witnesses by giving them money and instructions to provide false testimony, presenting false evidence and giving false testimony in the courtroom”, according to an ICC press release about the case. The ICC is also considering referring Mr Kenyatta’s case to the signatories of the Rome Statute, or to the UN, because of Kenya’s failure to cooperate, possibly with the aim of imposing sanctions. In October the ANC indicated that it was considering withdrawing South Africa from the Rome Statute. In the same month, the country asked the ICC for more time to formulate its response to the court’s request for an explanation of its handling of Mr Bashir. The ICC has given South Africa until December 31, 2015 to respond. These issues suggest that there is a long way to go before the ICC achieves worldwide, and especially African, credibility.

Annelie Rozeboom is a Dutch journalist and author. She is the editor of the Mada English Journal, Madagascar’s only English-language publication, and contributes to the IRIN Humanitarian News Service and Radio Netherlands Wereldomroep. Before moving to Madagascar, she was the China correspondent for the Dutch national newspaper Trouw. She has written four books about China, Tibet and Madagascar.