SDG 4: Education

Quality education in Africa looks like a hopeless case, but it’s a matter of taking the right steps

By Munyaradzi Makoni

Africa has high levels of inequality, between regions and within nations. Its countries also have different levels of development and different capacities to exploit their resources. These disparities can make it challenging to evaluate the continent against the economic and social yardsticks applied to developed countries. Today, four years after the UN approved its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, some African countries are inspiring hope, while others are generating little more than hopelessness. However, the opening in 2016 of the Sustainable Development Goals Center for Africa (SDGC/A) in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, is changing the landscape of reporting on Africa’s development. According to its website, “the purpose of the centre is to provide technical support, neutral advice and expertise as input to national governments, the private sector, civil society, and academic institutions to accelerate the implementation of the SDG agenda across Africa.” Another important development globally is the production of an annual SDG Index & Dashboards report for the continent produced by the Bertelsmann Foundation and the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN).

The second edition of the report, launched in 2017, included 99 indicators and extended the range of the previous one from 149 to 157 countries. The report aims to “collect and synthesise the most detailed, recent, available data on the SDGs from official and other verifiable sources to support national and regional discussions on where each country stands with regards to achieving the SDGs and on which metrics might be useful to track progress”. Prior to its launch in May 2018, SDG Center Director-General Belay Begashaw told a conference in South Africa that one major problem with collecting and comparing SDG data around the continent was that countries were sharing favourable SDG progress reviews but excluding reports on poor performance. The Africa-specific SDGs Index report attempts to address such problems. There is cause for soul searching around the continent on SDG 4 (quality education) figures in the Africa SDGs Index Report 2018. Out of the 54 African countries analysed for ensuring inclusive and equitable education and promoting lifelong learning for all, none has achieved so-called “green status” – meeting all indicators. According to the report, eight countries – Algeria, Botswana, Egypt, Gabon, Mauritius, Seychelles, South Africa and Tunisia, – lead on education. Twenty three countries – Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Comoros, Congo, DRC, eSwatini, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Morocco, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe – have made some developments, but are still at “some distance” from achieving them.

Facing “major challenges” were: Benin, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Chad, Ivory Coast, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea- Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Sudan. War-ravaged Libya and Somalia have no figures. SDG 4 places emphasis on primary, secondary, and technical and vocational education, only mentioning higher education twice. “SDG 4 is silent on the numerous and complex issues and challenges facing higher education in Africa,” says Damtew Teferra, professor of higher education at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. “It is intriguing that universities, which are major centres of research in Africa, are basically ignored, while their elements and activities are spread around the document,” he told University World News on 4 May, 2018. One African outlier, Mauritius, has done relatively well. There are good reasons for its relative success, says Goolam Mohamedbhai, former secretary-general of the Association of African Universities and honorary president of the International Association of Universities. The provision of free primary and secondary education was a key strategy for Mauritius from independence in 1968, he says. Boys and girls are ensured equal opportunities for accessing education. “The participation rate in tertiary education is at present over 40%, one of the highest in Africa, considering that for sub-Saharan Africa the tertiary enrolment ratio, on average, is of the order of 10%,” he told Africa in Fact.

Mohamedbhai further attributes Mauritius’ success in moderating its population growth rate, unlike most African countries. In 1960 the population growth rate was 3%, while it is now 0.25%, setting the tone for effective resource management for the country’s 1.3 million people. In a January 2019 New Year message, Mauritian Prime Minister Pravind Kumar Jugnauth announced a plan for free tertiary education for all up to bachelor’s degrees, which would further extend educational participation in the country. Good economic development and political stability has helped to provide a basis for good quality education in Mauritius, Mohamedbhai says. Formerly a low-income, agriculturally based economy, which grew into a middle-income diversified economy through developing its industrial, financial, technology and tourism sectors, Mauritius allocated $500,000 to education in 2018 and raised this amount to $544,000 in 2019. Politically, the country has benefited from regular, free and fair general elections and an absence of political upheaval or armed conflict since independence. But Mohamedbhai notes that work remains to be done in ensuring quality education in the island nation. “Completion rates are not very good,” he told Africa in Fact. “Rote learning, with limited opportunities to be exposed to independent learning and acquiring good communication skills, is another handicap.” He added that quality technical and vocational education had also not received enough attention.

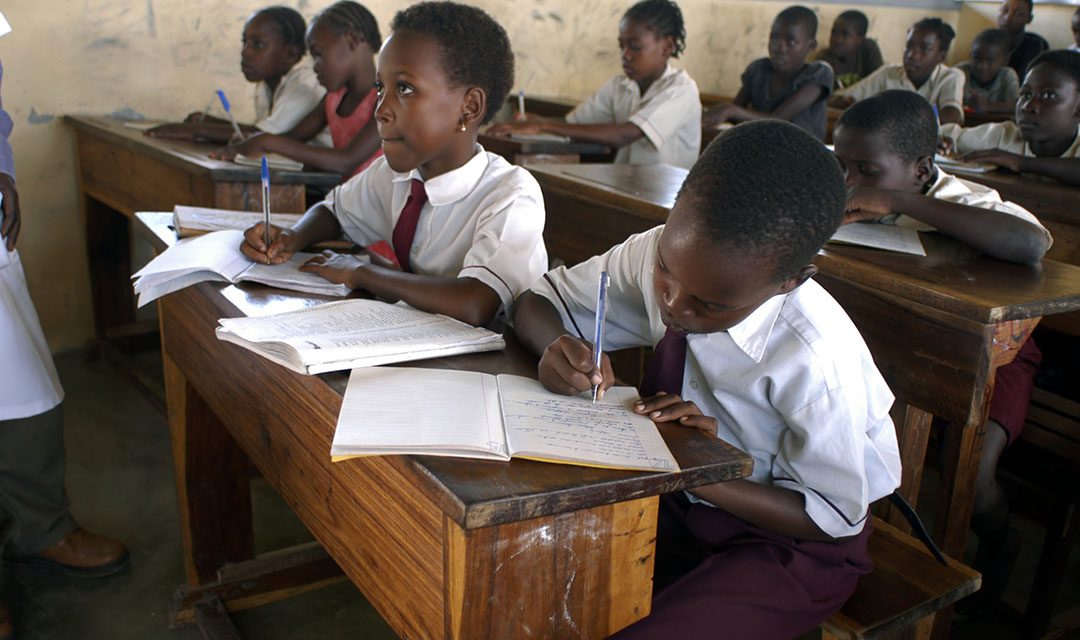

Ethiopia, one of the struggling countries, is different. School students are failing to achieve basic reading comprehension and writing skills in their mother tongue and in English, and basic innumeracy is common among children in grades 1-4. Generally poor levels of literacy have resulted in a high student drop-out rate, says Tayachew Ayalew, a former adviser to Ethiopia’s education minister and now manager of training and development at Mohammed International Development Research and Organization Companies (MIDROC). The problem persists in grades 5-8 and on into secondary school, where students’ achievements in subjects such as mathematics, English, physics, chemistry and biology poorly match other African nations, let alone global standards. Fewer children completing primary education means that fewer are getting into secondary school. Further, poor student achievement is rooted in the often poor quality of candidates attracted to the teaching profession, Ayalew argues. This, in turn, influences poor levels of teacher development – and the status accorded to teachers. “The respect given to teachers and the teaching profession is no more than lip service,” he told Africa in Fact. Teaching in Ethiopia is seen as a stepping stone to better opportunities, rather than as an opportunity in itself to develop a meaningful career. If Ethiopia is to improve its education system in line with the aspirations expressed by SDG 4 and, just as importantly, in line with the country’s aim to become a middle income economy by 2025, it will need to improve the status of teachers, motivate parent and community involvement, raise children’s expectations of education, and also provide youth employment opportunities through small and micro enterprises, Ayalew suggests.

The main obstacle to this, he reiterates, is the country’s lack of “human capital at middle and higher levels” of the education system. The country’s education system lacks well educated and motivated teachers and managers – in particular, people in these positions are themselves products of Ethiopia’s inadequate education. South Sudan can serve as an example of a country in the last ranking. According to the Africa SDGs Index, insufficient data was available to highlight many aspects of the country’s education system. John Apuruot Akec, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Juba, the oldest and largest public university in South Sudan, agrees. Unlike the rest of Africa, South Sudan is starting from a very low base because of 59 years of conflict, he told Africa in Fact in an email from South Sudan. “The country has no infrastructure or trained teachers, especially in primary schools, where 99% of teachers are secondary school leavers with no training in teaching,” he said. Moreover, the recent civil disturbances had seen the government divert both resources and attention from education to security. Proper planning and investment in education would be necessary to improve the situation, he said. One important measure in the shorter term, he added, would be to raise salaries to levels that would attract foreign-trained teachers to primary and secondary schools. Another important area to focus on would be enabling more girls to study at school.

“We need to improve girls’ enrolment and raise their secondary education completion rates by banning early marriages,” he told Africa in Fact. Increasing enrolment rates would provide a pool of better-educated candidates for teacher training. Akec also said there was a need to develop on-the-job training programmes for secondary school students as primary school teachers. The country faces the same vicious cycle that affects many poorly performing African states when it comes to education: a background of poor schooling does not generate good teachers. Achieving quality education in Africa might look like a hopeless cause, given that no African country looks close to achieving it. But as with any progress, this will be a matter of taking the right steps. The Africa SDG Index & Dashboards Report 2018 suggests a useful template that the countries of the continent can use in pursuing this goal. “Each African country [must] identify priorities of action, understand key implementation challenges, and identify the gaps that must be closed to achieve the SDGs by 2030.”

Munyaradzi Makoni is a journalist based in Cape Town, South Africa. He writes mostly on agriculture, climate change, environment, health, higher education, sustainable development and science in general. Some of his work has appeared in Hakai magazine, Intellectual Property Watch, IPS, Mongabay, Nature, Nature Index, Physics World, Science, SciDev.net, The Lancet, Thomson Reuters Foundation, and University World News, among others.