As electioneering ramps up ahead of the national election later this year, we can expect a marked increase in the proliferation of disinformation, misinformation, and fake news, aided by evolving artificial intelligence (AI) tools that make the discernment between true and false ever more difficult.

In the run-up to an election, it can not only fuel unrest but also compromise the credibility of the election itself. If voters are misinformed, for instance, about what political parties stand for or are unable to verify the claims made by parties about their track record in government, voting itself becomes redundant.

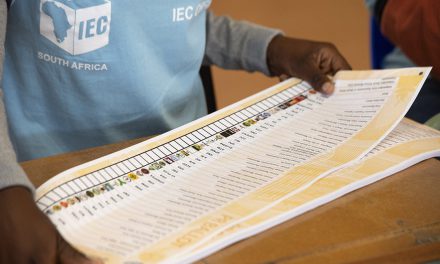

The Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC), noting recently that the burgeoning use of digital media has seen a corresponding surge in digital disinformation — particularly on social media platforms — has warned that “the dissemination of disinformation has huge potential to undermine the fairness and credibility of elections”.

“Credible information is the lifeblood of all democracies. Trustworthy information is crucial in the process that enables citizens to choose their leaders,” IEC chairperson Mosotho Moepya told IT Web media company.

To be clear on the difference between misinformation and disinformation, misinformation is false or inaccurate information — the facts are simply wrong (fake news). Disinformation is more cynical because it fits the mould of propaganda. It is false information that is deliberately intended to mislead. An example is a government overstating its military strength in a war.

An example of how misinformation can undermine a political party’s stakes in an election happened only a few months ago, to the Democratic Alliance’s MP Glynnis Breytenbach. A fake TikTok audio clip (now removed), circulated under the TikTok handle @bobbygreenhash, purportedly featured Breytenbach alleging that DA federal leader John Steenhuisen had leveraged the Western Cape as collateral for a multimillion-rand loan from the Bezos Foundation in America.

Incidents of misinformation and disinformation fuelling unrest or violence are well documented worldwide, including in South Africa. In Cape Town last year, during the taxi strike, voice notes and messages about the strike and attendant violence—later found to be untrue—were widely shared on social media, prompting Cape Town mayoral committee member for safety and security JP Smith to plead with people not to share content unless it was verified first-hand, because “it creates unnecessary panic, and also diverts enforcement resources from where they are needed”.

To combat disinformation in the months ahead, the IEC has partnered with Google, Meta and TikTok, as well as the nonprofit organisation, Media Monitoring Africa (MMA), to facilitate actions such as content removal, advisory warnings and delisting.

There is also recourse in the Cybercrimes Act of 2020, which, in the context of fake news or disinformation, provides that anyone found to have contributed to or knowingly disseminated false or defamatory content may be held civilly liable for defamation. The DA threatened to pursue this course after the Breytenbach incident.

But in the armoury against falsehoods proliferating online, these measures are the proverbial plaster over a wound that has already occurred. Much more important is prevention, in the form of awareness of what constitutes disinformation and misinformation and what makes one vulnerable to it.

In his book, Misbelief, behavioural economist Dan Ariely emphasises that in the face of ever-more convincing AI-tooled misinformation in greater quantities, “it’s important to remember that misinformation would not be nearly so effective were the human mind not so susceptible to these forces”.

“In fact, social media would never have become so popular without being built to take advantage of the faulty circuits affecting the way we react to information … Sure, some tech companies are working to create better guardrails and to improve our ability to spot fake news, but it’s a bit like a game of whack-a-mole that we can’t win. This is why we need to pay more attention to the human side of the problem,” he writes.

The “faulty circuits” that Ariely refers to are complex but natural human responses to an array of factors—including poverty, social disempowerment, economic inequality, and a universal human need to feel secure in a changing world—that diminish our ability to “keep multiple hypotheses in mind, and to remain open to new information and possibilities”. Under these compounding stresses, cognitive function and decision-making are compromised, he states.

Ariely has found that people tend to overestimate the likelihood of rare events and underestimate the probability of common events. In other words, we’re always looking for the simplest hypothesis that explains most of the variation in the data, but we’re not good at discerning what the complicating factors might be, or taking our assumptions to their logical ends. This can lead to the acceptance and belief in seemingly implausible conspiracy theories. And in seeking stories that confirm a bias, there comes a sense of relief, and a feeling of control over an otherwise uncertain or scary narrative.

He uses former US President Donald Trump as an example. “Ask yourself: If I hear a story or read a headline that tells me Donald Trump is making a secret deal with Putin, what’s my first response? A lot of people, if they’re honest, will admit they believe the stories without independently verifying them. Why? Because many people have already decided that Trump is a villain. And all of us—wherever we fall on the political spectrum — love to have villains to blame.”

Spreading the news is also a natural human response, but in the case of disinformation in the run-up to or following an election that already has temperatures raised, it can have a seriously destabilising effect. For example, the post-election violence that erupted in Nigeria in 2011 was partly fuelled by fake news promoting conspiracy theories, exaggerating the violence, and calling for further protests. In 2019, also in Nigeria, then president Muhammadu Buhari had to dispel a fake news story—viewed more than 500 000 times on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube—stating that he had died and been replaced by a Sudanese body double.

In his paper titled Democracy and Fake News in Africa, published in the Journal of International and Comparative Law, Charles Manga Fombad goes as far as to warn that “the increasing abuse and misuse of the internet and social media through fake news now threatens to reinforce the emerging decline towards authoritarianism in the continent”. What he infers is that democracy relies heavily on the dissemination of accurate and truthful information, the principle being that well-informed citizens are capable of making reasonable decisions and holding their leaders accountable.

Vigilance against disinformation and misinformation, therefore, is a duty of both the government and citizens in this election year, because a fair, unsullied outcome from the polls is essential to delivering us elected leaders who won without fear or favour.

How to spot mis- and disinformation

AI-generated disinformation is becoming more sophisticated and is increasingly difficult to spot. Carina van Wyk, head of education and training at Africa Check, says people can safeguard themselves against disinformation by asking themselves a few questions when reading online information. These are the questions she suggested you might ask:

· If it sounds too good, shocking or unlikely to be true, question it, pause and make sure you verify the information before you share it;

· If it triggers your emotions, if it makes you angry, or scared, or if it gives you hope, then pause, reflect and verify before you share it;

· If information is shared and looks like it’s becoming viral, look at credible news sources to verify the information;

· Ask yourself: who is the source of the information?

- With AI-generated images, look at the details such as fingers, ears, backgrounds and patterns, because artificial intelligence still often doesn’t get all the details right.

This article first appeared in Mail & Guardian on 16 January 2024.

Helen Grange is a seasoned journalist and editor, with a career spanning over 30 years writing and editing for newspapers and magazines in South Africa. Her work appears primarily on Independent Online (IOL), as well as The Citizen and Business Day newspapers, focussing on business trends, women’s empowerment, entrepreneurship and travel. Magazines she has written for include Noseweek, Acumen, Forbes Africa, Wits Business Journal and UJ Alumni magazine. Among NGOs she has written or edited for are Gender Links and INMED, a global humanitarian development organisation.