The African Group of Negotiators went to the United Nation’s climate conference (COP26) in November last year wanting a stronger finance architecture and climate rules that would enable them to manage their energy transitions justly and adapt to the “new climate normal” of more natural disasters.

The goal of COP26 was to ensure that countries adequately address the climate emergency by keeping alive the Paris Agreement’s temperature target of 1.5°C to avert catastrophic climate change. According to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, the earth has already warmed by an average of 1.1 °C from pre-industrial levels – making the Paris target not far off.

But for this target to be reached, countries must agree to urgently reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and to proactively pursue low-carbon, climate resilient development pathways. This would require the global transformation of the energy sector, and at least 40% of the world’s coal-fired power plants to be shut down by 2030 (and no new ones built).

The achievement of a 1.5°C target will also require enhanced ambition from all states – albeit in a self-differentiated way based on a country’s unique circumstances and capabilities. For developing countries, including those in Africa, a transition away from fossil fuels would require adequate financial and technological support from the developed world, especially given that historical emissions fall squarely on the North but the South is facing the brunt of these consequences.

In acknowledgement that existing commitments are insufficient, the Glasgow Climate Pact, signed in the final minutes of the negotiations, commits 197 member countries to accelerated action on climate change this decade. In the deal, countries have committed to come back by the end of November 2022, before COP27 in Egypt, with improved targets on cutting GHG emissions – much sooner than the previous five-year cycle.

For the first time the pact also includes the “phase-down of unabated coal power” and the “phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”. Although the initial text included stronger language, in a compromise to accommodate China and India, the text was revised from “phase out” to “phase down” of coal use. The economies of many developing countries still rely heavily on coal power and other fossil fuels (oil and natural gas) for energy generation.

Transitions towards low-carbon economies cost large amounts of money, affect workers and communities, and do not happen overnight. They can also catalyse socio-economic transformation through increased energy access and energy security, job creation and opportunities to harness new green finance, while simultaneously accelerating medium- and long-term environmental goals. Matched with COVID-19 economic stimulus packages and recovery plans, governments can create a revival that is both green and inclusive, with people at the centre. Technology developments, falling costs for renewable energies, innovative approaches, network effects and digitalisation are opening new opportunities and making an indisputable business case for renewables.

With abundant resources, Africa is well-placed to leverage this potential. However, the potential and availability of cost-effective technologies alone are insufficient. Seizing this opportunity will require strong political will, attractive investment frameworks and a holistic policy approach to fully reap the benefits of renewable energy.

At its core, a move to a low-carbon economy must ensure that the gains and losses from the transition are shared equitably and do not exacerbate existing inequalities. A just transition approach requires citizen engagement and participatory processes that consider diverse viewpoints – including gender and youth. This would require capacity building, training, and upskilling.

Also, without a faster shift towards low carbon ambition and net-zero goals, countries stand to face major economic consequences. According to South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, “South Africa’s trading partners are likely to increase restrictions on the import of goods produced using carbon-intensive energy. Because South Africa’s industry depends on coal-generated electricity, the products we export to these countries might face trade barriers. Consumers there may be less willing to buy our exports”. In addition, many financial organisations have committed to fossil fuel divestment, meaning that coal and oil will no longer be financially supported. For example, three of South Africa’s major banking institutions — Rand Merchant Bank, Nedbank, and Absa – have committed to stop funding new coal-fired projects within five years.

One announcement that has the potential to become a model for partnership between developed and developing countries is the deal struck between South Africa and the European Union, France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, worth $8.5 billion, to help finance a quicker transition away from coal towards renewable energies.

In advance of COP26 South Africa ramped up its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) ambitions to 2025 and 2030, but it was clear that achieving these new goals required a “just transition transaction”. South Africa has the largest carbon footprint in Africa and is the world’s 12th highest carbon emitter because of its huge dependence on coal for energy. Retiring coal plants without supporting stranded coal workers and communities (some 100,000 work in this sector) would exacerbate the country’s already high unemployment and poverty. This agreement aims to help the country achieve a just transition.

South African president Cyril Ramaphosa. Photo: AFP

The Glasgow agreement also touches on concerns that richer nations are reneging on their responsibility to help poorer countries heavily impacted by the crisis. The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that Africa will need investment of more than $3 trillion in mitigation and adaptation by 2030 to effectively implement its NDCs. Developed countries promised to substantially increase their target of $100 billion a year of financing for developing countries beyond 2025. But since the $100 billion target, set for 2020, has still not been met, it remains to be seen whether this promise – like many others – will be kept.

While Africa has been consistent in its call for developed countries to support developing regions in addressing the financing, technology transfer and capacity building needs related to ambitious climate action, there is also a need for enhanced domestic resource mobilisation and capacity development in support of African-led and African-owned climate responses.

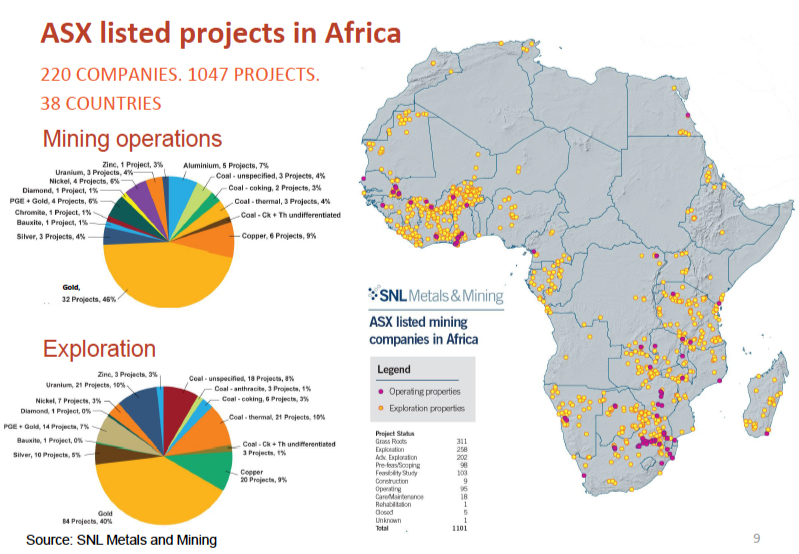

Finance is not the only factor. Glasgow urged developed countries to provide support for technology transfer. Decarbonisation is the new “space race”. Achieving it is good for the planet, but those with technological strategic autonomy in this field will also cement their overall geopolitical power. African countries cannot afford to be caught in geopolitical tussles. Green technology is essential to help with African countries’ economic diversification. Forty-two of 63 elements used by low-carbon technologies and 4IR hardware are found in Africa. This is a strategic opportunity for African states to leverage their mineral resources in ways that advance their developmental and transformational objectives and makes them not just consumers but also producers of green technology.

To date, Africa has contributed less than 4% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and yet has substantial adaptation needs. The Glasgow Pact includes a pledge to at least double the amount of money given to help developing nations for adaptation to more than $40 billion a year. The question is whether the developed world will raise ambition and deliver on their financing commitments.

COP26 saw the launch of a work programme on the global goal of adaptation, which was a significant development for African countries. However, after resistance from some developed countries, the Glasgow Pact failed to secure the establishment of a dedicated new damages fund for which vulnerable nations had pushed. The Least Developed Countries Group, as well as small island developing countries, expressed “extreme disappointment” at the decision to initiate only a “dialogue” to talk about “arrangements for the funding of activities for loss and damage”. The Glasgow deal did agree to fund the Santiago Network, a body that aims to build technical expertise on dealing with loss and damage, such as helping countries consider how to move communities away from threatened shorelines.

A Global Climate Strike protest on 24 September 2021, in Cape Town, demonstrating against the causes of global climate change, and in particular, the South African Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE). Photo: Rodger Bosch/ AFP

According to UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, “the approved text is a compromise, reflecting the interests, conditions, contradictions and the state of political will in the world today”. Guterres said, “while taking important steps, the collective political will was not enough to overcome some deep contradictions and accelerate action to keep the 1.5 °C goal alive… “Our fragile planet is hanging by a thread, and we are still knocking on the door of climate catastrophe.”

The building blocks and pledges delivered at COP26 need to urgently be translated into action through robust and rapid policy implementation. This will require ambitious leadership and collective action from all countries, and from all stakeholders across economies, including Africa. National plans must include long-term, transformative approaches that integrate mitigation and adaptation activities across all key economic systems; the creation of favourable conditions to phase out coal and scale up renewables and low-carbon transport; the expansion of sustainable food and land systems, including forest landscape restoration and biodiversity protection, and investment in resilient water infrastructure and key industrial value chains. In addition, measuring and reporting mechanisms need to accompany climate policy frameworks to enhance monitoring and accountability.

The delivery of climate finance is essential so that all countries can deliver on more ambitious targets by 2030 and beyond. However, without support from the developed world, vulnerable economies, and those in transition, are unlikely to meet the ambitious targets needed to close the emissions gap. To support these goals, the international community, including the private sector, should demonstrate leadership and bolster support efforts to encourage accelerated action.

Would you like to gain an understanding of your own impact on the environment? Calculate your own carbon footprint here

Romy Chevallier is a senior researcher in the Governance of Africa’s Resources programme at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA). Romy is also an independent consultant focusing on issues related to climate policy and stakeholder engagement in Africa.