Africa’s industrialisation

Why manufacturing is key to creating jobs and building diversified economies

Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana produce 53% of the world’s cocoa. But the supermarket shelves in Abidjan and Accra, their respective capitals, are stacked with chocolates imported from Switzerland and the UK, countries that do not farm cocoa.

This scenario is repeated throughout the continent in different contexts. For example Nigeria, the world’s sixth-largest producer of crude oil, exports more than 80% of its oil but cannot refine enough for local consumption. In 2013 it spent about $6 billion subsidising fuel imports, estimated Finance Minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala late last year.

In such apparently baffling scenarios lies one of Africa’s greatest challenges— and opportunities. The continent possesses 12% of the world’s oil reserves, 40% of its gold and between 80% and 90% of its chromium and platinum, according to a 2013 report from the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). It is also home to 60% of the world’s underutilised arable land and has vast timber resources. Yet together, African countries account for just 1% of global manufacturing, according to the report.

This dismal state of affairs creates a cycle of perpetual dependency, leaving African countries reliant on the export of raw products and exposed to exogenous shocks, such as falling European demand. Without strong industries in Africa to add value to raw materials, foreign buyers can dictate and manipulate the prices of these materials to the great disadvantage of Africa’s economies and people.

“Industrialisation cannot be considered a luxury, but a necessity for the continent’s development,” said South Africa’s Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma shortly after she became chair of the African Union in 2013.

This economic transformation can happen by addressing certain priority areas across the continent.

First, African governments, individually and collectively, must develop supportive policy and investment guidelines. Clearly-defined rules and regulations in the legal and tax domains, contract transparency, sound communication, predictable policy environments, and currency and macroeconomic stability are essential to attract long-term investors.

Moreover, incentives—such as tax rebates to multinational companies that provide skills training alongside their commercial investments—will help local economies grow and diversify. In addition, each industrial policy should be tailored to maximise a country’s comparative sector-specific advantages.

Mauritius, one of Africa’s most prosperous and stable countries, provides important lessons for other African countries. In 1961 this Indian Ocean island nation was reliant on a single crop, sugar,

which was subject to weather and price fluctuations. Few job opportunities and yawning income inequality divided the nation. This led to conflict between the Creole and Indian communities, which clashed often at election time, when the rising fortunes of the latter became most apparent.

Then from 1979 on the Mauritian government took practical steps to invest in its people. Realising that it was not blessed with a diversity of natural resources, it prioritised education. Schooling became the critical factor in raising skills and smoothing the lingering religious, ethnic and political fractures remaining since independence from Britain in 1968. Strong governance, a sound legal system, low levels of bureaucracy and regulation, and investor-friendly policies reinforced the country’s institutions.

Under a series of coalition governments, the nation moved from agriculture to manufacturing. It implemented trade policies that boosted exports. When outside shocks hit—such as loss of trade preferences in 2005, and overwhelming competition from Chinese textiles in the last 15 years—it was able to adapt with business-friendly policies.

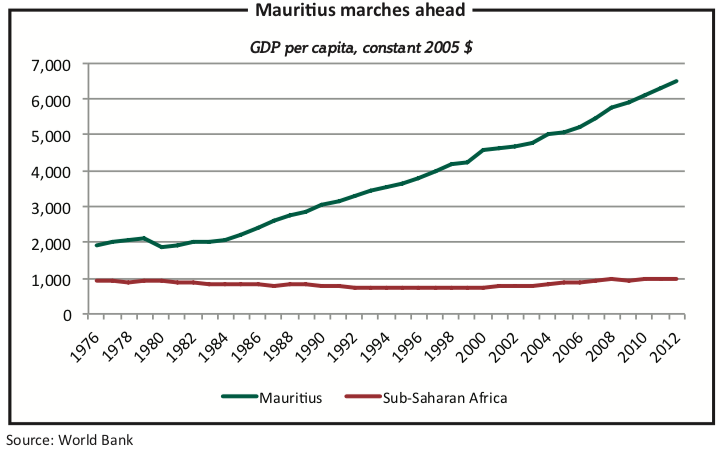

From being a mono-economy reliant on sugar, the island nation is now diversified through tourism, textiles, financial services and high-end technology, averaging growth rates in excess of 5% per year for three decades. Its per capita income also rose from $1,920 to $6,496 between 1976 and 2012, according to the World Bank.

While much responsibility lies with African governments, the continent’s private sectors must play their part in improving co-ordination between farmers, growers, processors and exporters to increase competitiveness in the value chain and ensure the price, quality and standards that world markets demand.

Tony Elumelu, chairman of Nigerian-based investment company Heirs Holdings, and Carlos Lopes, the executive secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, advocate what they call “Africapitalism”, a private sector-led partnership focused on the continent’s development. “Private-sector business leaders must also do more to tackle poverty and drive social progress by ensuring that long-term value addition—as well as short-term gain—is built into their business model,” they wrote in a joint article for CNN in November 2013.

Next, African countries must pursue beneficial economic strategies with their neighbours. Regional integration would help reduce the regulatory burden facing African industries by harmonising policies and restraining unfavourable domestic programmes. It would boost inter- and intra-African trade and accelerate industrialisation.

The right recipe for regional integration requires countries to concentrate on commodities in which they have a competitive advantage. For example, Benin and Egypt could concentrate on cotton, Togo on cocoa, Zambia on sugar each country trading in bigger regional markets.

Agriculture, which employs over 65% of the continent’s population, according to the World Bank, could be- come a springboard towards industrialisation. It can provide raw materials for other industries, as well as promote what economists call backward integration, in which a company connects with a supplier further back in the process, such as a food manufacturer merging with a farm.

This is already under way in Nigeria. The diversified BUA Group “will process 10m tonnes of cane to produce 1m tonnes of refined sugar annually”, according to Chimaobi Madukwe, the company’s chief operating officer.

Sustained investment and improvements in infrastructure are also needed throughout the continent. Countries everywhere, not just in Africa, cannot establish competitive industrial sectors and promote stronger trade ties if saddled with substandard, damaged or non-existent infrastructure.

“Developing industries require sustained electricity supply, smooth transportation and other very basic infrastructure facilities, which at present are still not enough to ensure operations,” said Xue Xiaoming, vice-chairman of the Nigerian Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

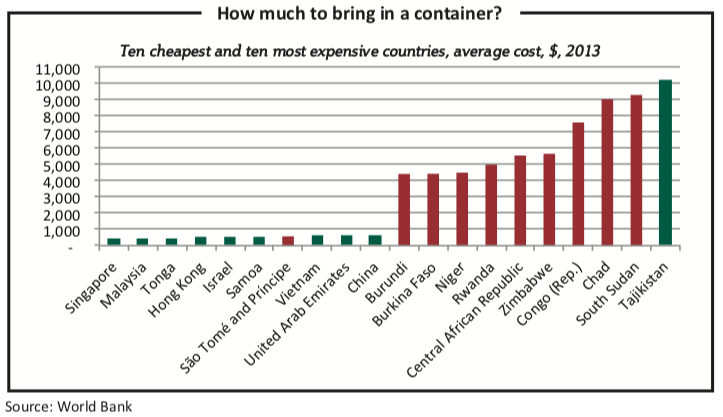

Africa’s poor roads, railways and other transport networks, faulty communications, and unreliable and insufficient energy result in high production and transaction costs. It takes 28 days to move a 40-foot container from the port of Shanghai, China to Mombasa, Kenya at a cost of $600, while it takes 40 days for the same container to reach Bujumbura, Burundi, from Mombasa at a cost of $8,000, explained Rosemary Mburu, a consultant at the Institute of Trade Development in Nairobi. “This represents double the time at 13 times the cost,” she said.

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) should be developed to stimulate massive investments in infrastructure, which could have a multiplier effect on economic growth. Finally, without education the continent cannot succeed in its drive towards industrialisation. PPPs should be pursued in this arena too, because governments often lack the skills and finances to carry out technical training. Private sector companies would benefit from a skilled and competent workforce. The country would benefit from a stronger economy blessed with less unemployment and higher incomes.

Historically, countries have succeeded by focusing on education in science and technology and promoting research. For example, in the 1960s and 1970s South Korea —like Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong—reformed its education system and made elementary and high school compulsory.

From an adult literacy rate of less than 30% in the late 1930s, South Korea now boasts a literacy rate of nearly 100% and has one of the highest levels of education anywhere in the world, according to UNESCO, the UN’s education agency. Its highly- skilled population has helped South Korea to become one of the world’s foremost ex- porters of high-tech goods.

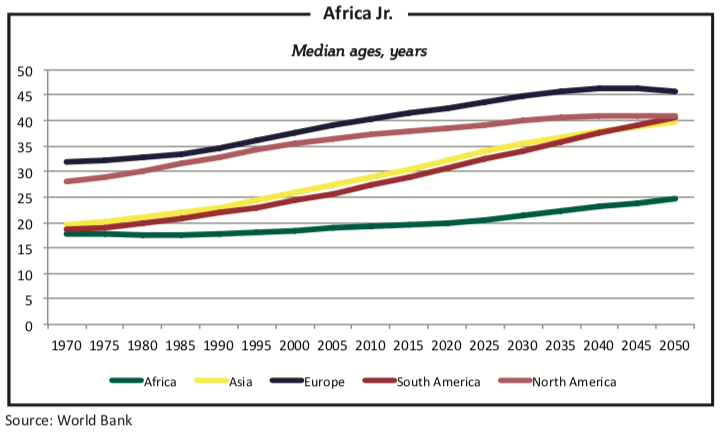

Africa, the world’s youngest continent, is currently undergoing a powerful demographic transition. Its working-age population, which is currently 54% of the continent’s total, will climb to 62% by 2050. In contrast, Europe’s 15-64 year-olds will shrink from 63% in 2010 to 58%. During this time, Africa’s labour force will surpass China’s and will potentially play a huge role in global consumption and production. Unlike other regions, Africa will neither face a shortage in domestic labour nor worry about the economic burden of an increasingly ageing population for most of the 21st century.

This “demographic dividend” can be cashed in to stimulate industrial production. An influx of new workers from rural areas into the cities, if harnessed correctly and complemented with the appropriate educational and institutional structures and reforms, could lead to a major productivity boom. This would then increase savings and investment rates, spike per capita GDP, and prompt skills transfers. Reduced dependency levels would then free up resources for economic development and investment.

Without effective policies, however, African countries risk high youth unemployment, which may spark rising crime rates, riots and political instability. Rather than stimulating a virtuous cycle of growth, the continent could remain trapped in a vicious circle of violence and poverty.

The continent’s youth represent a huge potential comparative advantage and a chance to enjoy sustained catch-up growth. Or they could remain shackled in joblessness and become a major liability.

Africa is ripe for industrialisation. A strong and positive growth trajectory, rapid urbanisation, stable and improving economic and political environments have opened a window of opportunity for Africa to achieve economic transformation.

RONAK GOPALDAS is a director at Signal Risk, an exclusively African risk advisory firm. He was previously the head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) for a number of years, where he managed a team who provided the firm with in-depth analysis of economic, political, security and operational dynamics across sub-Saharan Africa. He holds a BCom degree in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) and a BCom (Hons) from the University of Cape Town (UCT). He also has an MSc in finance (economic policy) through the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.[