South African political economist, Moeletsi Mbeki © Wiki Commons

African states and multinational corporations must trust each other in order to stop illicit financial outflows, and spur growth and development

Mistrust between business and government is an abiding constraint on development in Africa. The African Union (AU) and other state-driven organisations often say the private sector should drive growth in African economies and that the continent’s states should establish frameworks for business to succeed — but in reality, it hardly happens this way.

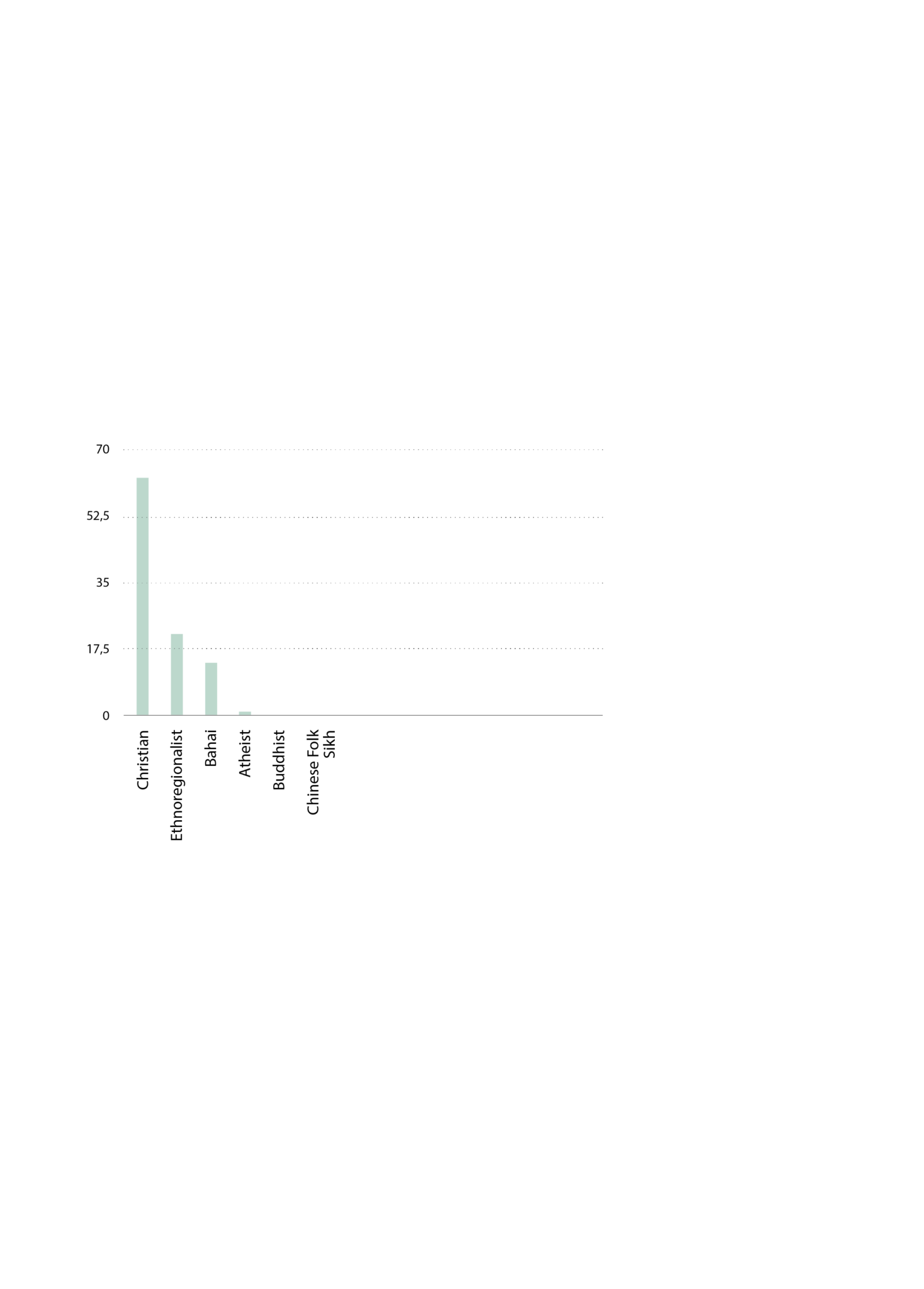

The AU and its member states see the state as being central to development. Meanwhile, big business, particularly Western multinational corporations (MNCs), is often vilified in Africa as an exploitative and anti-development force — and a lingering legacy of colonialism. Two new reports by the AU and the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) give this perception new impetus. A 2015 report, Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, conducted by a specially appointed AU high-level panel, points to MNCs as the main culprits in the illicit transfer of an estimated $60 billion to $80 billion out of Africa each year. The report says MNCs are to blame for about 65% of such outflows. It defines “illicit outflows” as money illegally earned, transferred or used. This mainly takes place, it says, through tax evasion but also through transfer pricing, which involves moving taxable profits from high-tax to low-tax jurisdictions.

Another path is trade mis-invoicing, which involves deliberately misreporting the value of transactions to a country’s customs service. Other culprits identified by the panel were criminals, who it said were responsible for an estimated 30% of such outflows, and corruption, which it said accounted for 5% of illicit outflows.

The report adds Africa’s voice to global efforts to combat illicit flows. But illicit outflows are not a simple problem to solve, says Peter Draper, managing director at Tutwa Consulting, a South Africa-based firm that focuses on the regulatory and policy issues that affect businesses. Defining their components and measuring them is difficult, he told Africa in Fact.

Moreover, the world of global trade and investment involves multiple jurisdictions that allow legal loopholes and tolerate secrecy. It can be difficult to track the beneficial ownership of a company or use of front companies to move money around the globe. Meanwhile, creative accounting and disclosure are facilitated by tax havens — some in Africa — and the lack of country-by- country reporting by MNCs. In Africa, capacity constraints and governance issues add to the difficulties involved in tracking and policing illicit outflows.

But given the benefits of investment from MNCs, solving the problems requires finding a balance between better policing of cross-border activities without compromising investment flows, says Draper. “Even if we don’t agree on the figures, we can agree there is a big problem and that we need to find a way to solve it.”

The narrative of MNC exploitation is also central in the ECA’s 2016 report, Investment Policies & Bilateral Investment Treaties in Africa: Implications for Regional Integration. The report examines the prevalence, scope and value of bilateral investment treaties, and argues that Africans are victims of such treaties, which favour the interests of Western nations.

Both reports stereotype MNCs and play to suspicions about the nature and drivers of profit, particularly where they are independent of government influence. Unsurprisingly, they have been welcomed by African leaders and continental bureaucrats, whose focus is usually on African-owned small and medium enterprises, rather than the large corporations and MNCs which they characterise as “enemies of development”.

In the AU high-level panel report, for instance, the head of the panel, former South African president, Thabo Mbeki, refers to the “aggressive and illegal activities” of MNCs, suggesting that corrupt Africans are simply victims of their well-resourced activities. But to demonise global business is to create an environment that is hostile to capital. Companies will prefer to keep their money in business-friendly jurisdictions if they can. It follows that the AU and its members are themselves partly to blame for the malaise.

There will always be companies that take advantage of weak institutions and corrupt governments. But many MNCs, particularly those bound by international conventions and onerous compliance requirements, prefer to operate in environments where the rules are clear and the laws and policies are upheld by strong institutions.

Governance is still highly personalised in Africa and therefore subject to “capture” by competitors and policy makers. Company tax revenues are often misdirected to personal or politically expedient projects. In turn, many in the private sector — including MNCs — do not trust governments to serve their interests. Their investments can involve high risk levels, including operating in high-cost and inefficient markets and in unpredictable policy environments.

Moeletsi Mbeki, a South African political economist, says in the modern world, capital is highly mobile and will always seek good returns and receptive environments. “When you restrict investment opportunities, capital moves elsewhere, illicitly or otherwise,” he told Africa in Fact. African governments focus on redistributing wealth rather than creating it, he argues. This, he says, is a colonial hangover — an attempt to rectify historical injustices by “eating” rather than investing. The result is the creation of anti-investment environments that “perpetuate the poverty of African economies”.

Africa must stop money leaving the continent, certainly. But it must also maximise revenue generation within the continent. Take the case of mining. The sector, dominated by MNCs, has been a key driver of growth but its potential contribution has been undermined by a trust deficit between MNCs and governments. Governments believe mines have massive wealth that they are determined to conceal or externalise illegally, says Dr Greg Mills, director at the Brenthurst Foundation, based in Johannesburg, South Africa. Meanwhile mining concerns complain that the politicians who set the rules do not understand the long-term and cyclical nature of their business, nor the levels of risk they face.

African governments tend to play to popular public pressure to extract more and more out of mining companies based on short-term needs rather than engaging the industry as a long-term developmental partner, Mills adds. “Yet the overall health of the sector is intrinsically in the interests of government, not just for reasons of long-term revenue, jobs and the prospects of industrialisation, but because many governments hold a direct stake in mining operations.”

The AU has set up initiatives and structures in recent years to connect with business. Key among them is the African Mining Vision, adopted in 2009 to chart a roadmap towards the transparent, equitable and optimal exploitation of mineral resources in Africa. The AU is also working with the New Partnership for Africa’s Development on several initiatives, including the Continental Business Network, an advisory platform focused on infrastructure.

But the level of distrust between the public and private sectors remains a constraint on the success of such initiatives. Continental bureaucrats seldom understand the on-the-ground realities of doing business in Africa, preferring to concern themselves with the big-picture rhetoric of African development that dominates continental debates. Meanwhile, business leaders do not always have time or willingness to participate in long conferences that yield little result. Most just want governments to set fair rules and regulations, create a level playing field and reduce the risks and costs of doing business.

The mistrust malaise is not helping efforts to develop Africa. Indeed, it is having the opposite effect and it is probably one of the key drivers of illicit outflows from Africa to other, possibly more friendly, jurisdictions. Companies with long-term plans involving Africa will likely welcome political initiatives to improve transparency and introduce new rules, as long as they are fairly and efficiently applied.

The problems of illicit financial flows are global, and solutions need to be global. This will take time. Meanwhile, the AU can change the nature of its engagements with MNCs. Casting MNCs as inherently exploitative or as criminal actors is simply lazy. Ignoring that their activities involve huge benefits in terms of tax revenue and employment, among others, is simply short-sighted. The AU should build partnerships with MNCs to encourage them to commit meaningfully to Africa’s future