Oil-rich Angola is one of the most talked-about investment destinations in Africa, but behind the economic boom there is an impoverished and disenfranchised population burdened with some of the worst social indicators on the continent. Elections in late August are unlikely to improve their fortune. Louise Redvers looks at why the oil money is gushing for a few and dribbling down to the rest.

Luanda’s ever-expanding glass and steel skyline stands as a proud symbol of Angola’s impressive post-war economic growth.

Thanks to its vast oil reserves, the country has more than bounced back from the decades of isolation and conflict that ended in 2002. Between 2004 and 2008 its gross domestic product (GDP) rocketed by an average of 17% a year, reaching 22% in 2007, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This year its economy is expected to expand by over 9%.

Angola topped the continent in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows in 2010, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). It is now sub-Saharan Africa’s third-largest economy behind South Africa and Nigeria with a rapidly expanding banking sector and a growing portfolio of investments in Portugal and beyond.

However, away from Luanda’s shiny new bay-front promenade with its palm trees imported from Miami and freshly-watered grass, there is another Angola.

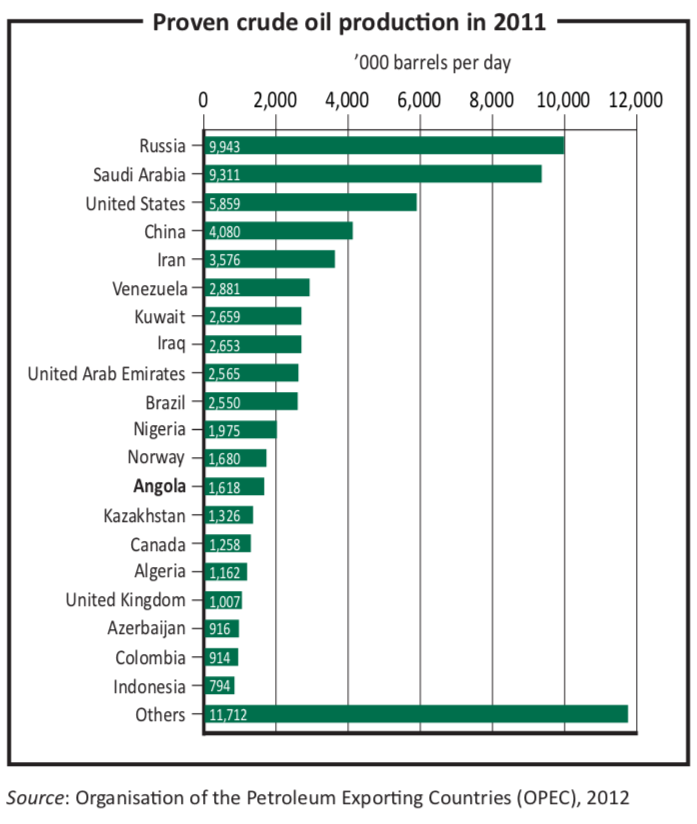

Despite the billions of dollars of oil revenues pouring into the country—Africa’s second biggest crude producer after Nigeria and the main supplier to China—the government’s own statistics show that half of the population still live on less than $2 a day and one in five youngsters dies before the age of five.

Slum-style neighbourhoods, known locally as musseques or bairros, stretch for miles around the capital, housing about 4m people in overcrowded and unhygienic conditions. In rural areas, most families survive on subsistence farming. They live in huts of mud and wattle. Conditions have barely changed in decades.

Countrywide, schools are understaffed and overcrowded. Clinics lack skilled personnel and medicines. Unemployment and crime rates are stubbornly high.

The government recognises the need for improvement and is spending oil money on social and infrastructure projects. Billions of dollars have been poured into roads and bridges. The country’s three railway networks are expected to be fully operational again by 2013. Airports and ports have been upgraded to increase capacity.

Billions of dollars have also been spent on schools and hospitals. There will soon be universities in all 18 provinces. New housing developments are going up everywhere aiming to clear slums and reduce overcrowding.

Many feel, however, that changes have not come quickly enough, given how much money the government has had at its disposal and the small size of the population, estimated at 19m.

Oil provides about three-fourths of the government’s revenue. Economists at the World Bank and the IMF have long been calling for Angola to diversify its economy by establishing a stronger private sector that can create jobs and help distribute the wealth.

There are moves in the right direction, with various investments designed to restore the once-profitable agricultural sector, boost local manufacturing and give small businesses start-up loans.

But Elias Isaac, country director at Angola’s office for the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA), sees these as token gestures by a government which he and others see as running the country for the benefit of themselves, not the majority.

“It is not in the interests of individuals within the elite to see Angola diversify its economy,” he says, explaining that most businesses are run by people in or directly connected to the ruling party, the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola). Allowing other people to become independently wealthy would weaken the party’s grip on power.

“When you have people making this much money from importing food, they are not going to want to develop agriculture, nor are the people making all the money from generators going to want more electricity infrastructure. There are too many conflicts of interest, development is not a priority,” Mr Isaac explains.

Jon Schubert, who is pursuing a PhD at Edinburgh University evaluating political authority and modalities of power in post-war Angola, acknowledges the irony of a formerly Marxist liberation party now being so disconnected from its electorate.

“The overriding feeling that I have from my research is that the Angolan elite just doesn’t really care about the population at large,” he says. “The gap is so wide between the elite and the majority, they are like different people from a different country.”

The Angolan government misses no opportunity to defend itself against its critics. It blames the length and scale of the war and the impact that it had on human capacity and institutions for the country’s problems.

Senior figures also accuse “international forces” of trying to stoke up rebellion among the Angolan youth to destabilise the government, warning people against an Egypt-style uprising that could re-start the war.

Angolan journalist and anti-graft campaigner Rafael Marques says corrupt officials are exacerbating Angola’s problems. Government departments are spending public money wildly without proper consultation, he adds.

Bearing testimony to this theory are white elephant projects such as football stadiums built for the 2010 Africa Cup of Nations, the massive Chinese-built housing estate where apartments remain unsold one year on, and the government’s ability to run up $9 billion worth of debt to overseas construction firms in 2009.

Mr Marques also alleges that patronage money is splashed around to maintain the MPLA’s grip on power, even though the party holds an 82% majority in parliament and passes any law it wishes.

He refers to this patronage process as “co-opting” and says it is an approach regularly used on journalists, civil society activists and the Catholic church, a staunch critic of government during the war years.

Others claim that the government’s controlling nature, its stranglehold on state and private media and intolerance of criticism, undermine Angola’s claim to be democratic.

The former prime minister, Marcolino Moco, has accused President Jose Eduardo Dos Santos, who has been in power for nearly 33 years without being elected, of running a “one-man state” using the country’s oil wealth to serve his own ends.

There are widely-reported doubts about how much of the money from Angola’s oil exports actually makes it into the government’s official coffers. Its oil exports surged to more than $49 billion in 2010, according to the IMF, which also recently noted that between 2007 and 2010 as much $32 billion of state money went “missing” from the books.

Brave investigations by Mr Marques, whose reports have led to his arrest on several occasions, are aiming a new spotlight on the small Angolan oil outfits that are making billions of dollars from signing lucrative contracts with international oil companies. Members of Mr Dos Santos’ family own some of these firms.

The United States regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission, has launched a probe which is looking at the state petroleum company Sonangol’s former chief executive officer, now minister of state for economic co-ordination, Manuel Vicente.

Mr Vicente, likely to become Angola’s vice-president after the election, is alleged to have awarded an equity stake in a lucrative offshore oil concession to a company in which he had shares. Mr Vicente denies any wrongdoing and says he no longer owns any shares in Nazaki Oil and Gas, which is in partnership with Cobalt International Energy Inc., a US-based exploration firm.

OSISA’s Mr Isaac wants the international community to pay more attention to Angola and for overseas companies to consider the ethics of their business deals.

“These companies come from countries where principles of transparency and good governance are upheld, so they have a moral obligation to uphold such values when operating in Angola,” he says.

“They also have a moral responsibility towards the Angolan people whose resources they are extracting, because this oil is not going to last forever and once it has gone, what about the impoverished people they will have left behind?”

More immediately though, the population’s anger is rising at the government’s failure to share the country’s wealth more evenly.

A string of rare public protests by youth groups calling for Mr Dos Santos to resign have ruffled the feathers of the authorities. Former military veterans, supposedly the backbone of the MPLA, have also taken to the streets to demand unpaid pensions.

Human Rights Watch and other international groups have criticised the government’s heavy-handed response. They have raised concerns about reports of “hired thugs”—supposedly linked to the MPLA—who have been targeting individual protestors, injuring them at demonstrations and raiding their homes.

The protests, while small, are extremely significant in the Angolan context where the importance of “keeping the peace” after a 27-year civil war is promoted by the government to curb unrest. Furthermore, few dare to criticise authority for fear of losing their jobs or being shunned by party networks.

Angola holds a legislative election on August 31st.

The MPLA won an 82% majority in 2008, Angola’s first peacetime election. (The 1992 poll was abandoned mid-way due to fighting.) The ruling party is certain to win again, not only because of its incumbency advantage, but also through its control of the media and state resources. The opposition are complaining bitterly about what they say is fraudulent management of the electoral system.

Under the terms of the country’s controversial new constitution, the head of the party with the most votes will automatically become president. Thus Mr Dos Santos, who turns 70 three days before polling, will more than likely be handed a new five-year term.

“I am pessimistic about the elections because I can’t see the MPLA in its current incarnation accepting a significant loss of votes, just as I can’t really see the opposition or students accepting them winning another 70% to 80% majority,” Mr Schubert says. “The potential for escalation around the elections is really quite worrying.”

Since the end of Angola’s war in 2002, the international and business community have lauded Mr Dos Santos for maintaining political stability, allowing oil companies and investors to make money without any of the troubles and constraints seen in places such as Libya, Nigeria or Sudan.

If that scenario changes, the unwavering investor support for his government may start to wane.

Louise Redvers is a freelance journalist who has reported from Angola, Swaziland and Zambia for the BBC, the Mail and Guardian, The Africa Report and other media. After five years in Africa, she recently relocated to the Middle East.