In his biography on Cyril Ramaphosa, Prof Anthony Butler memorably remarked that not many of the president’s speeches had been memorable. Ramaphosa’s most recent state of the nation address (Sona), delivered on February 9, will go down as memorable not so much for its substance but because it was delivered presidentially.

In other words, the delivery was decisive and clear, almost authoritative. Tone counts for a large portion of how a speech lands, and the president struck a useful combination of being emphatic and empathetic. He was emphatic that no one should be left behind, and empathetic towards the fact that we are living within a complex set of crises.

We should also, then, be emphatic that this was the beginning of a serious campaign for the governing party to try to retain its majority at the 2024 national election. One cannot help but notice that Ramaphosa’s recognition of multiple crises purposefully created distance between the problem and the president. He spoke of the electricity and Covid-19 crises as if they were things that happened to us by exogenous force; vague impositions over which we had no control.

That subtly suggests that the very governing party over which the president presides somehow had no role to play in the poor governance decisions that exacerbated the socioeconomic devastation caused by Covid-19, or in the malfeasance that created the current electricity crisis. The pandemic did not create the loss of two million jobs: poor governance responses, especially declaring a state of disaster and shutting down the economy unnecessarily in many cases, cost us two million jobs.

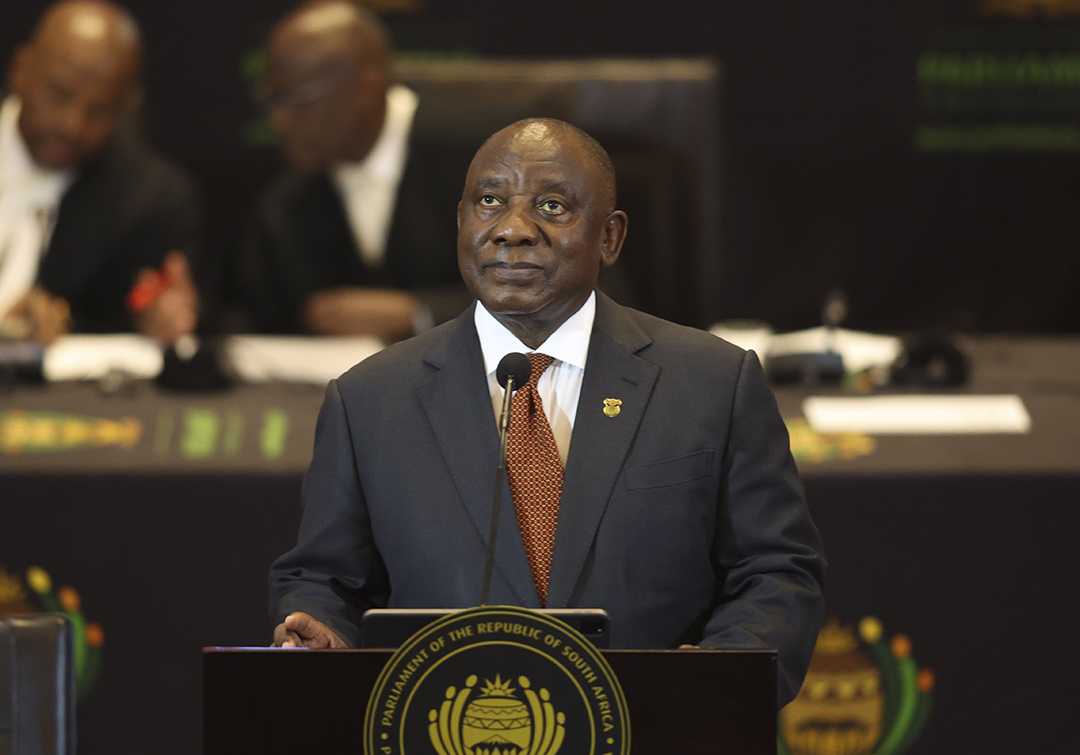

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa looks on during the 2023 state-of-the-nation address (SONA) at the Cape Town City Hall in Cape Town on February 9, 2023. (Photo by ESA ALEXANDER/ POOL/AFP)

Recognising a disaster for what it is does not equate to owning responsibility for overseeing its creation. We recognise that the president has been politically constrained and inherited a complex set of dynamics from the state capture days (which of course are not over simply because we have lengthy Zondo reports about them). Nonetheless, no president can hide behind collective accountability, and he could have removed many more people within the party who fomented and benefited from state capture.

In his speech the president declared another state of disaster, over which the co-operative governance and traditional affairs minister will preside. Leaders are often fatally attracted to silver bullet solutions that end up creating more problems than they solve. It seems likely that this is one of those instances. A state of disaster is typically disastrous for democratic accountability, and declaring one does not make the governance problems that created the problem go away. To the contrary, it creates darkness under which corrupt contracts proliferate, especially given that many officials who benefited from state capture remain in their posts.

It was not clear from the president’s speech exactly how the creation of an electricity minister within the presidency will actually fix the load-shedding problem, which now costs the economy roughly R1bn a day in lost productivity. That is one more minister alongside that of public enterprises, mineral resources and energy, and co-operative governance and traditional affairs. This accumulation of power within the presidency poses a risk to the quality of our democracy. One imagines family meetings where only the father speaks, and we’ve seen that movie before.

Of course, it is appropriate to give prominence to the electricity crisis. But the ministers now tasked to fix the problem are from the very party that allegedly engaged in corrupt boiler contracts that account for the rapid reduction in Eskom’s energy availability factor (EAF) over the last three years. It also oversaw cost overruns and time delays at Medupi and Kusile. The president mentioned that a chimney stack at Kusile collapsed in 2022; such nonchalant recognition. This is meant to be a state-of-the-art power station. Chimney stacks only collapse because of poor oversight in the construction process.

The president also mentioned Eskom’s debt, ballooning partly because municipalities owe the utility billions of rand. Lest we forget, Eskom’s debt is more than R400bn. That is nearly a third of the country’s annual budget. Debt servicing costs are a major portion of that budget, and they will only grow unless we can grow the tax base. In fact, unless we rapidly grow the tax base, we will not be able to afford the expansive annual growth in the public sector wage bill, which is currently about 42% higher than total annual personal income tax revenue. As it is, a minuscule proportion of the population — about two-million people — contribute the majority of personal income tax paid to the fiscus.

On that note, we have to recognise that “more than 25-million people receiv[ing] some form of income support” is unsustainable. Two-million taxpayers cannot feasibly support 25 million others. While it is laudable that such support exists, and sometimes creates the means for expanding the workforce, it is no substitute for meaningful job growth. The president did not mention that the Reserve Bank’s most recent growth forecast for 2023 is 0.3%. And the monetary policy committee noted in January that “while the economy grew by a relatively strong 1.6% in the third quarter of 2022, the expansion was not broad-based”.

There is simply no way that such sclerotic growth can absorb labour. To create meaningful jobs, the productive sector has to grow. It cannot grow without investment. While the president’s emphasis on fixing roads, rail, ports, energy and water provision is welcome in this respect, investment is equally dependent on governance — transparency, accountability and the rule of law.

Take mining for instance. The president only mentioned the industry in passing — that red tape will be reduced in the mining rights processing system. He failed to mention, despite having given an address at the Mining Indaba just two days prior, that unless the mining sector grows fast, there will be a significant revenue hole in the budget in 2023. SA is currently at risk of missing out on yet another commodity boom.

Yes, mining recovery depends on energy, port and rail infrastructure getting fixed, but it also depends on creating an operating environment strongly built on the rule of law, and we still do not have a functional, transparent cadastre system that operates licensing allocation. That is not a red tape problem; that is a problem of zero political will.

Insufficient political will also hinders the creation of a framework that would make coalition government more stable at local level. As it stands, the incentives are stacked towards disruption over delivery. The president’s attention in his speech towards local government matters is welcome. However, if it is to improve and deliver services to citizens, political parties will have to be credibly deterred from behaving the way the EFF did in advance of the president’s speech. It behaves this way in local coalitions too, because it has the most to gain from disruption.

On matters of service delivery, many parts of the country have recently gone without water for days on end because power outages create problems for water reticulation. The president was buoyant about phase 2 of the Lesotho Highlands water project starting in 2023. He did not mention the cost. Nor did he mention that this new supply, while critical, will be entirely obsolete unless the reticulation infrastructure is fixed. The volume of water lost to leakage in SA, an increasingly arid country, is criminal. Again, new projects are no compensation for a lack of maintenance over the last 25 years.

Finally, the credibility, or lack thereof, of the president’s speech will be made manifest in whoever he chooses to be in his new cabinet. The quality of his cabinet is all-important. If it does not change significantly we will have to conclude that the speech was mere electioneering, which most South Africans will rightly see through.

You can read the full State of the Nation Address here.

Dr Ross Harvey is a natural resource economist and policy analyst, and he has been dealing with governance issues in various forms across this sector since 2007. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town, and his thesis research focused on the political economy of oil and institutional development in Angola and Nigeria. While completing his PhD, Ross worked as a senior researcher on extractive industries and wildlife governance at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), and in May 2019 became an independent conservation consultant. Ross’s task at GGA is to establish a non-renewable natural resources project (extractive industries) to ensure that the industry becomes genuinely sustainable and contributes to Africa achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ross was appointed Director of Research and Programmes at GGA in May 2020.