The wave of democratisation in sub-Saharan Africa in the wake of the Cold War was met with widespread scepticism. Many observers portrayed democratic reforms as mere “window dressing” to satisfy western aid donors, unlikely to alter dysfunctional patterns of governance seen in much of the region. Yet three decades later, African democracies outperform their autocratic counterparts on key indicators of governance quality – such as government effectiveness and corruption control.

Explaining democracies’ superior record does not require blind faith in abstract democratic ideals. Crucial advantages of democracy are grounded in the accountability mechanisms they provide, which offer periodic opportunities for inclusive groups of citizens to remove governments by constitutional means. Even where democratic accountability mechanisms are far from perfect, they allow democracies to outperform their autocratic counterparts.

UK lawyer Khawar Qureshi (R) speaks with prosecutor Dorcus Oduor at the Milimani Law Courts in Nairobi, Kenya, in December 2018, before the trial of the country’s second-highest judge, Deputy Chief Justice Philomena Mwilu, on corruption charges. (Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP)

To illustrate the logic of political accountability, I begin by thinking through a simple game in which two hungry robots interact strategically to divide cakes. The real-world analogy is to citizens’ struggles to ensure that public resources are devoted to their collective well-being, instead of being diverted or squandered by their government. Then I return to the real world and evidence about democracy and its effects on the quality of governance in Africa.

Imagine infinitely repeated interactions between two robots named Government and Constituency. At the beginning of each term, a cake falls from the sky and lands in the hands of Government. Constituency would like Government to give it the largest possible slice. To achieve this, it uses its power to retain or remove Government at the end of each term (If it removes Government, an otherwise identical robot takes its place in the next term, and the game continues as before). Constituency pursues its interests by demanding a specific share of the cake each term, threatening to remove Government if its demand is unmet.

Like supercomputers programmed to play chess, we can programme Government and Constituency to play the much simpler cake-slicing game optimally. The key question is how much cake Constituency should demand, knowing that Government is programmed to make its best available response. If Constituency demands too little, Government will happily oblige, but Constituency will be left with less cake than if it had been more ambitious. If it demands too much, Government would be left with too small a sliver to make it worth meeting Constituency’s demand. It will prefer to abscond with the whole cake, knowing it will be removed, rather than facing a future in which, though retained, it will be forced to subsist on small slivers every term for perpetuity. Constituency, by demanding too much, risks ending up with nothing.

Constituency’s best play is to demand the largest slice it can, just short of tempting Government to abscond. Computing the optimal demand precisely requires just one additional piece of information: Government’s time horizons. They reflect the value Government places on current cake versus cake it will only get in the future (that is, its “discount rate”). In the simple cake-splitting game, with plausible time horizons and optimal behaviour by both robots, Constituency will succeed in using its political leverage to secure nearly all the cake in every term.

The accountability mechanism so far has given Constituency perfect control over Government’s fate: it can retain or remove Government at the end of each term with certainty. But what if, as may be more realistic, the mechanism is less reliable?

A supporter of United Democratic Party (UDP) youth wing holds up a placard as he takes part in an anti-corruption protest in Banjul, Gambia in March 2023. (Photo: Muhamadou Bittaye/AFP)

Consider one that is prone to random misfiring. Sometimes Constituency intends to retain Government, but Government is removed anyway. Other times Constituency tries to remove Government but fails. The first case might reflect ambient political risk: the possibility that, say, a foreign invasion, domestic insurgency, or other “shock” removes Government even though it has fulfilled constituency’s demand. The second might reflect flaws in the removal process – for example, electoral fraud and violence, or other political loopholes that give a non-delivering Government some chance to cling to power.

The robots can be reprogrammed to divide the cake with an accountability mechanism that fires only probabilistically. Unsurprisingly, as the mechanism becomes less reliable, the amount of cake Constituency can use it to get cake from Government decreases. The stakes are not all-or-nothing, though. Constituency can still secure a healthy slice of the cake with an imperfect mechanism. Only when its ability to influence Government’s political fate becomes the exception not the rule does Constituency’s slice shrink to a sliver.

The cake-eating robots have analogies in the messier real world of democratic accountability. Constituency might represent a broad, inclusive segment of society – say a majority of voting-age citizens. The accountability mechanism might be periodic national elections in which citizens can retain or remove their government. Constituency’s slice of the cake might be a quantum of public goods that enhance citizens’ welfare, while Government’s slice represents public resources diverted to private interests or squandered.

Such analogies break down if the accountability mechanism is not even vaguely democratic. Without a constitutional means for citizens to decide whether to retain or remove their government, the government’s political fate will hang on less reliable processes, such as military coups, factional political purges, armed insurgencies, or popular uprisings. Not only does the mechanism’s unreliability weaken accountability, but the “constituency” – defined as those with the most influence over whether the government survives – narrows to specific, politically pivotal minorities.

LEFT: Former Comorian President Ahmed Abdallah Sambi, arrives at the courthouse in the capital, Moroni, in November 2022. Sambi was originally placed under house arrest for disturbing public order and later placed under pre-trial detention for embezzlement, corruption and forgery over a scandal involving the sale of Comorian passports to stateless people living in Gulf nations. RIGHT: Former Algerian prime minister Ahmed Ouyahia, who is serving a 15-year prison sentence for corruption, is escorted by police after attending the funeral of his brother in the capital, Algiers, in June 2020. (Photo: Ibrahim Youssouf, Ryad Kramdi/AFP)

Rather than being accountable to an inclusive segment of society as in a democracy, a government in an autocracy must appease specific groups pivotal to its political survival. Although these narrow “constituencies” may make effective demands on the government, they will tend to be demands most readily satisfied through targeted transfers of resources or other forms of patronage – unlike the broadly beneficial public goods needed to satisfy democratic constituencies.

As a result, the link between political accountability and governance quality is likely to be more tenuous in autocratic settings – because accountability mechanisms under autocracy are less reliable, and because autocratic governments must cater to the demands of narrower, less inclusive constituencies.

Turning from robots to the real world, what do the effects of democratic accountability on the quality of governance look like in sub-Saharan Africa? “Governance quality” here refers to the effectiveness of the state in formulating and implementing public policy, and to controls that prevent public resources from being diverted corruptly for private gain. Democracies are classified using a “minimalist” definition of electoral democracy, in which a majority of adult citizens has a reasonable chance to remove an incumbent government in a competitive election if they choose to do so.

LEFT: Ndambi Guebuza, wearing an orange prison uniform, talks to his father Armando Guebuza, the former president of Mozambique, during a trial for corruption and financial fraud held in a maximum-security prison in Maputo in February 2022. RIGHT: Former South African President Jacob Zuma, who is facing charges of corruption, money laundering and racketeering, consults with his legal team during a recess at the High Court in Pietermaritzburg, in January 2022. (Photo: Alfredo Zunigae,Jerome Delay/AFP)

Meanwhile, the closest thing to cakes falling into African governments’ hands are rents from lucrative mineral and fuel resources. “Rents” are the profits from selling these resources on world markets, beyond the costs of extraction. For countries with established resource sectors, rents are easy to tax, because resource extraction remains remunerative despite heavy taxation. Countries with ample resource rents most closely resemble the cake-splitting game.

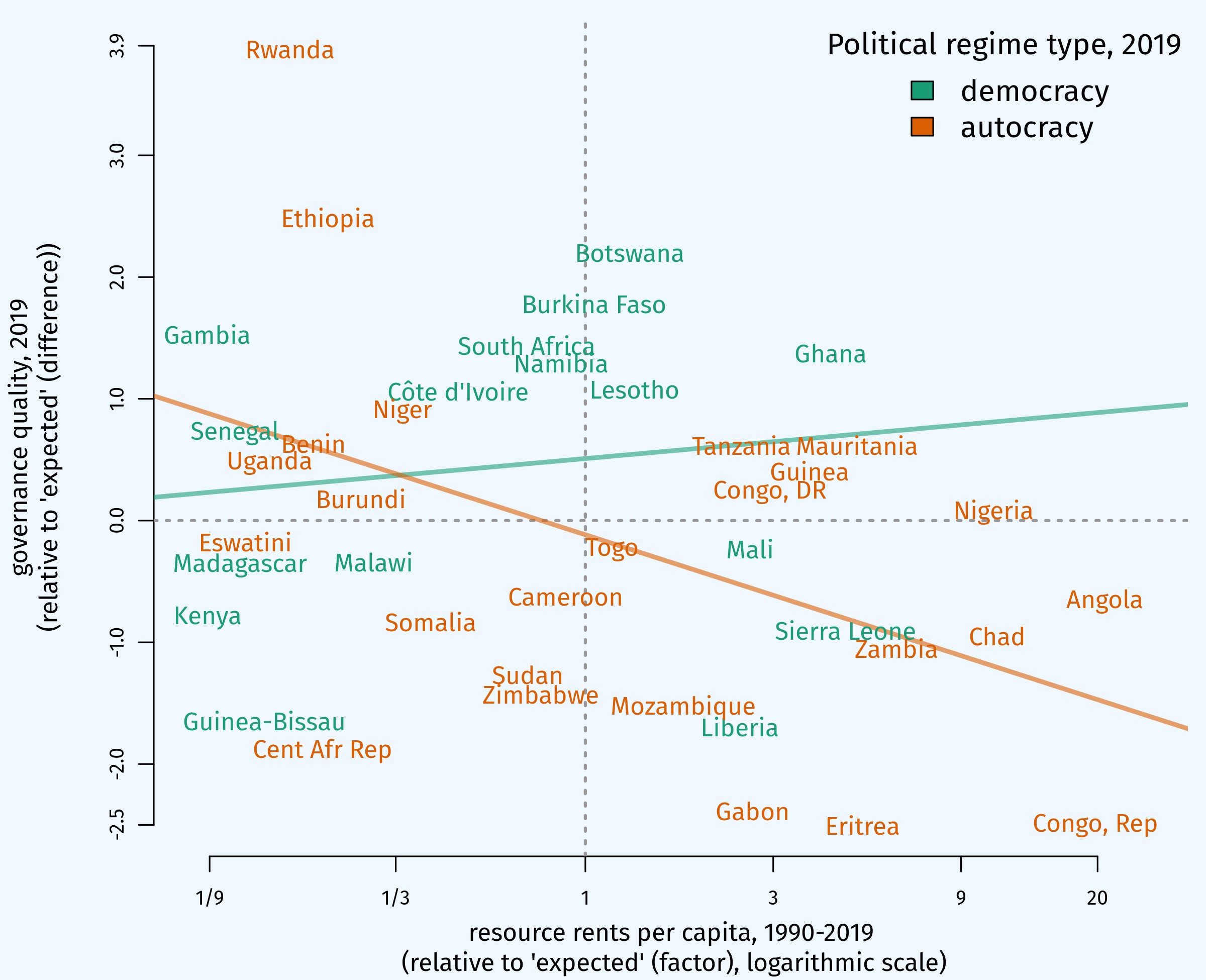

Figure 1 contrasts the relationship between resource rents and governance quality in African democracies versus autocracies (It does so while controls statistically for two potentially confounding factors – non-rent gross domestic product [in 1990] and cumulative political risk [as of 2018]).

Figure 1: The contrasts between resource rents and governance quality in African democracies and autocracies. Source: Rod Alence

The trend lines show that for autocracies the quality of governance drops significantly as rents increase, while for democracies it is stable or even improves slightly. At the left of the figure, where rents are low, governance quality is a mixed bag for democracies and for autocracies, and it is difficult to discern any clear advantage. Moving to right, however, where increasing rents provide larger “cakes” for splitting, autocracies perform distinctly worse – with less effective governance and more corruption – while no such pattern emerges among democracies.

As the cake-eating robots illustrated, democratic accountability mechanisms empower citizens to get more from their governments. The evidence from sub-Saharan Africa confirms that democracies are in fact outperforming autocracies in delivering good governance. The democratic advantage is most pronounced in countries where the discretionary rent “cake” is the largest. It emerges despite the many defects of real-world democracies in Africa, as long as citizens have a realistic chance of removing governments through competitive elections if they so choose. Despite widespread scepticism about African democracies, the empirical record shows that they do govern better than their autocratic counterparts – and the cake-eating robots help explain why.

Rod Alence is Associate Professor in International Relations at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he has been based for twenty years. At Wits, he developed and coordinates a Master’s programme in computational social science. His research focuses on the political economy of development and democracy. He is currently involved in a multi-year, multi-country research project on election observation and peace-building in Africa, with colleagues from the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor) and the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa. He received an AB degree from Columbia University and MA and PhD degrees from Stanford University. While doing his doctoral research, he was a Fulbright scholar at the University of Ghana, and his thesis won the American Political Science Association’s annual award for best in the field of political economy.