Heritage: the long shadows of past and present

Commemorating heritage in Africa is no longer the exclusive province of governments

People dressed in traditional

costume welcome guests to the opening ceremony and inauguration of the new museum of black civilisations in Dakar, Senegal, on 6 December, 2018. Photo: SEYLLOU / AFP

There was an interesting exchange between Thabo Mbeki and Constand Viljoen in the late 1990s. The former was an aristocrat of an African liberation movement who would become South Africa’s president, and the latter was the chief of the country’s apartheid-era defence force, a soldier’s soldier and politician. Both had a keen sense of the manner in which the past echoes into the present. Responding to a rancorous debate on white settlement in the country, Viljoen objected that his forebears had come to South Africa “because we wanted to be free burghers, not to colonise”. Mbeki responded: “Phew! We have a long way to go. There is a different understanding of the history of the country, a different understanding of the realities of the country.” That sentiment is still relevant to South Africa’s politics, and possibly even more acutely now two decades after this conversation took place.

And while South Africa may at times be a somewhat hyperbolic example, it is far from a unique one. For in Africa the past looms large over the present – probably more than anywhere else on earth. Heritage is the memorialisation and veneration of that past, and of the culture that has grown up within it. It is a society’s memories, its rituals, its artefacts, statues and architecture, its sense of history. For many, it justifies their claim on belonging to a society. Africa’s history is perhaps unique for the degree to which it has been mediated through external lenses, often denying the role of Africans as originators of their stories. “There was a refusal to see Africans as the creators of original cultures, which flowered and survived over the centuries in patterns of their own making,” wrote Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow, former director general of the United Nations Economic and Social Council, in the General History of Africa in 1993. Indeed, the colonial experience not only intruded into memory, but commandeered much of its tangible heritage.

A report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron found that “over 90% of the material cultural legacy of sub-Saharan Africa remains preserved and housed outside of the African continent”. Among these were the magnificent Benin bronzes, seized in 1897 when Benin City was sacked and torched by a British expeditionary force. Some of these were auctioned to defray the costs of the invasion. A treasure of African art – and an inspiration for the modernist movement – they reside for the most part in museums outside Africa. The colonial powers liked to leave memorials of their presence in Africa. In southern Africa, this meant memorials of a heritage that celebrated the European offshoot societies that remained. They were part of the African story, but for African nationalists celebrating this has represented an uncomfortable reminder of past subjugation. Post-liberation, there was a powerful impulse to remove these tokens of memory. “We want to wipe the slate clean and present our image of independent Zimbabwe without these vestiges of colonialism,” said former president Robert Mugabe in 1984, four years after the country’s independence.

By that time, Zimbabwe had replaced Rhodesia, the colonial capital Salisbury had become Harare, and street names that had once proudly declaimed a connection to British empire were replaced with ones saluting African nationalism. Zimbabwe was but one example. Colonial Gold Coast became independent Ghana in 1957 – the new name harking backing to an eponymous medieval empire. Most recently, Swaziland was renamed eSwatini, in 2018. Africa’s past intrudes directly into its present-day and speaks to the brand of politics that holds sway in many countries, says Steven Gruzd of the South African Institute of International Affairs. “History is ever present in African politics,” he said in an interview with Africa in Fact. “Some parties are decades, or [even] a century old, and [they] hark back to what they see as glorious, heroic histories. In states where liberation wars were fought, such as in southern Africa, this past is frequently evoked and glorified.” This is the politics that both Mugabe and Mbeki, in different ways, represented.

Society could and would be remade along the lines of a new narrative. A revisioned heritage would underwrite a new moral order. Yet, in practice, the concept of “heritage” is troubled and ambiguous. Whatever the dreams of nationalist politicians, the impact of the colonial era has proved virtually impossible to expunge. Most African states owe their borders to their colonial experiences, and they conduct much of their business in English, French and Portuguese. Governance systems draw heavily on this connection, too. The physical remnants of colonialism linger. Some potentially portable signifiers of that history have demonstrated a remarkable tenacity. Architecture predating independence, which was often meant to convey dominance and permanence, remains visible in many African cityscapes. Despite Zimbabwe’s determination to reinvent itself, and its later turn to outright racial nationalism, a statue of the Scots explorer and missionary Dr David Livingstone remains prominently in place at the Victoria Falls (now known, too, as Mosioa- Tunya, or “the smoke that thunders”).

“What is clear is that Zimbabwe has a conflicted relationship with its colonial past and relics,” the Zimbabwean journalist Farai Mudzingwa comments, speaking for much of the continent. Elsewhere, reminders of the colonial past have slipped by ignored, or have been commandeered to provide energy for the tourist trade. Ironically, when Zimbabwe suggested removing the statue of Dr Livingstone, neighbouring Zambia asked to take possession of it, seeing it as a tourist drawcard. Tours of Kenya cash in on its colonial past as showcased in movies such as Out of Africa. In Nigeria, the city of Lokoja, a colonial-era state capital, tries to do likewise, attracting magazine headlines such as “Lokoja: Colonial Town, Rich History”. Excising the past may not be as simple as the liberationist narrative would have it. In a society such as South Africa vocal constituencies have championed retaining the country’s colonial heritage. These have involved both court challenges and physical stand-offs.

An Afrikaans singer, Sunette Bridges, chained herself to the Kruger memorial in Church Square in Pretoria (or Tshwane) in 2015 after calls for its removal. Cultural activists saw the call not just as a threat to physical artefacts but to the legitimacy of a cultural minority’s presence. Some heritage is difficult to pigeonhole. Large numbers of Africans fought in colonial armies in the second world war. They were subject people forced into supporting colonial overlords, certainly; yet theirs was also a contribution to a moral conflict against unspeakable evil. Numerous video clips celebrating this now circulate on social media. In collaboration with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Nigeria has recently repurposed preexisting monuments by incorporating them into a new memorial in Abuja. The memorial records the names of Nigerians killed in both world wars and is surmounted by a pair of bronze sculptures depicting a Hausa rifleman and an Igbo porter made in the 1930s by the British artist James Alexander Stevenson.

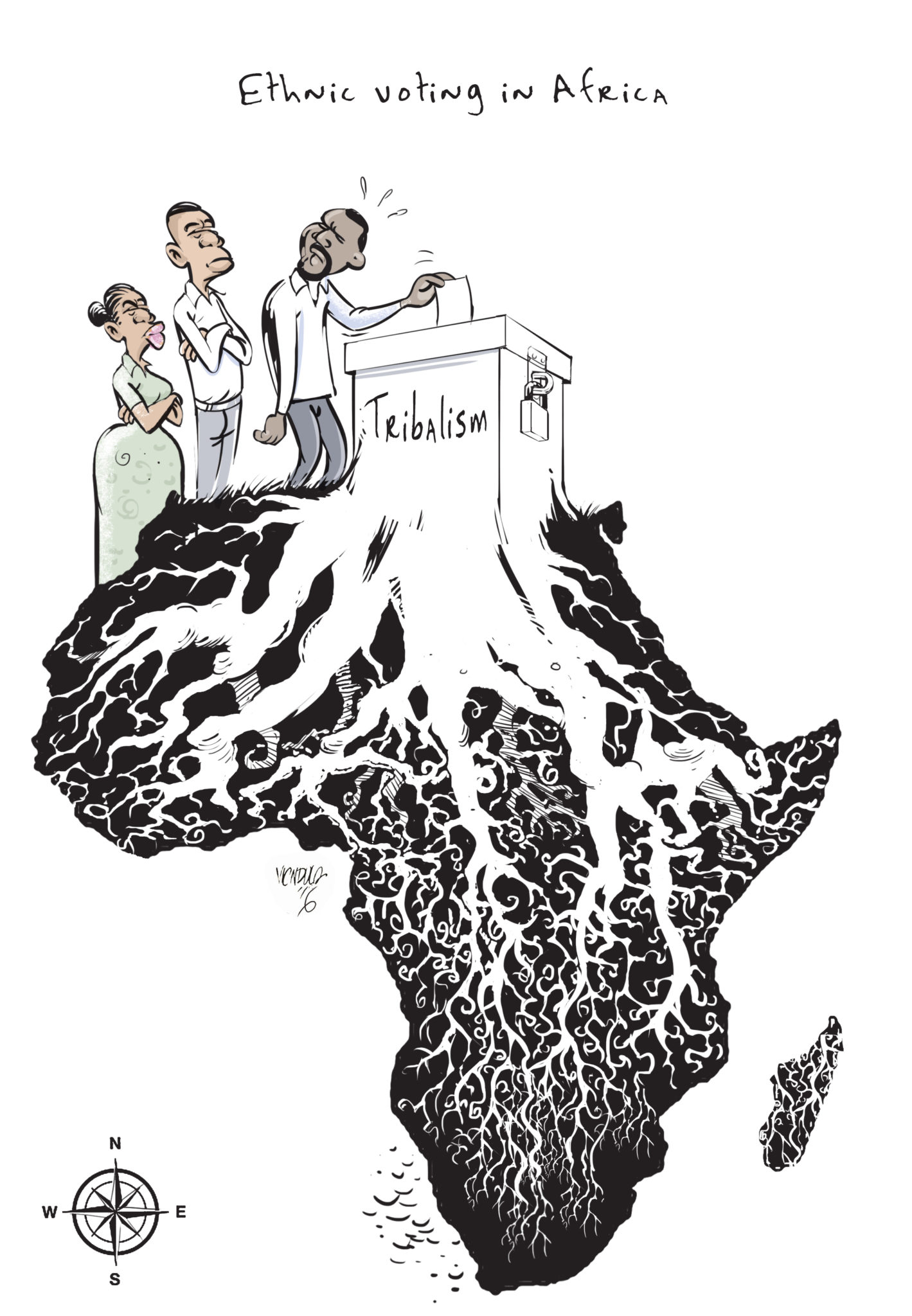

Dealing with Africa’s colonial heritage is challenging. Memorialising what has transpired in the generations since independence may prove even more so. Stevenson’s depiction of Nigeria’s multi-ethnic contribution to the first world war might uncannily have presaged its later politics. Nigeria’s nascent nationhood was nearly destroyed in the brutal war that accompanied the attempted secession of the Republic of Biafra in the 1960s. It was a trauma from which the country has never entirely recovered. For decades, it was official policy to downplay the conflict in the interests of a new Nigerianism, with the result that there are few public memorials to it; even displays about the conflict at the country’s National War Museum are controversial. This is a Whiggish interpretation of history – that is, an interpretation of history in the service of the present, says Nigerian museum curator Iheanyichukwu Onwuegbucha in a recent paper, “The National War Museum Umuahia: Representation of the Biafra War History”.

The fact the Biafran war occurred, and the continuing silence about it, can be seen as expressions of ongoing ethnopolitics. For people with memories of Biafra, the official narrative indicates that the Nigerian state has never attempted an appropriate historical reckoning of its own conduct. Rwanda’s 1994 genocide is powerfully remembered in monuments and social rituals, and – perhaps more importantly – in the country’s political culture. But there, remembering, rather than forgetting, is just as much a two-edged sword. Resisting “genocide ideology” has become a catch-all justification for measures that hurt civil liberties and restrict political opposition. Even without traumas such as these, an unsettled post-colonial past challenges the present. Post-colonial African states embodied aspirations for development and nation building.

Some of them have produced near-messianic figures to deliver on these goals – resulting in profound frustration when these all too often proved to be a disappointment. Post-colonial monuments rise and fall according to political fashion, says Martin Plaut of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies. Perhaps the most glaring example of this accompanied the deposition of Ghana’s founding father, Kwame Nkrumah. An outsized figure in his time, a sculpture of the former leader stood prominently before the presidential mansion, but the statue was decapitated after Nkrumah was ousted in 1966. Even more symbolically, parts of the statue have been preserved separately, perhaps in memory both of the former leader and of the coup that toppled him. Another example is the African Union’s controversial erection of a stature of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie at its Addis Ababa headquarters.

“Emperor Haile Selassie is an example of how leaders have gone in and out of fashion,” says Plaut. “The movements they led wax and wane — and with them go the reputations of those who led them.” Haile Selassie’s statue is recognition of his role as a champion of African freedom against colonial intervention, Plaut adds. Yet the emperor is also remembered as the last representative of a feudal order, and for his personal aloofness. A report by Human Rights Watch in 1991 described the “official indifference” to famine during his reign, for example. Across the continent, the reputations of some of Africa’s post-colonial icons – such as Kenneth Kaunda in Zambia or Julius Nyerere in Tanzania – have come under critical scrutiny. The University of Ghana removed a statue of Mahatma Gandhi, another towering personality of the anti-colonial movement, citing the “racist attitudes” he expressed in his younger days.

Rather astoundingly, the reputation of Jean-Bédel Bokassa of the Central African Republic (CAR) – and self-proclaimed emperor of the short-lived Central African Empire – has enjoyed something of a recovery. He was long remembered as a man of sinister brutality and farcical pomp, but some today see his rule as a time of progress and development that his successors have failed to match. In 2010, then CAR President François Bozizé issued a decree formally “rehabilitating” him. In Kenya, the country’s political elite once decried the memory of the Mau Mau uprising as “hooliganism”. This has been reassessed and at least partially accepted as an honourable part of the struggle for independence. A museum has now been established to relay this narrative. In recent years, the importance of preserving Africa’s heritage has gained growing recognition. The opening in 2018 of the enormous, multi-storey Museum of Black Civilisations in Dakar was emblematic of this.

Intended as a record of Africa and its offshoot societies, its design and facilities are impressive and its ideological messaging fitting. Senegal’s first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, was an exponent of Negritude, a philosophical movement celebrating blackness and Africanism. Hopes have been expressed that the museum will play a role in securing the repatriation of items carted off during the colonial era. Yet this may not be Africa’s most difficult challenge. African societies will need to navigate the meaning of the continent’s heritage for the present. A good starting point is to acknowledge the obvious: heritage is not intrinsically a force for unity, since it remembers factious and divided pasts. “All history is the story of conflict, humiliation and division,” says Plaut. “As one historian put it, imperialism is the natural order of human history.”

Conflicting claims about the past are an intrinsic part of a plural society, and as such they are not altogether negative. Commemorating heritage is also no longer the exclusive province of governments. Africans are today experimenting successfully with alternative models of commemoration, such as localised community museums or online memorials. New layers are inexorably being added to the continent’s memories. The ambiguity of Africa’s heritage must be acknowledged. And in this sense, Thabo Mbeki was profoundly mistaken. A common understanding of the past is not possible. The challenge for South Africa – and the continent as a whole – is not to find a single set of memories and understanding, but to accept their multiplicity.

Terence Corrigan is an independent researcher, political consultant, writer, editor and illustrator. He is currently a research fellow at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) in its Governance and African Peer Review Mechanism Programme and a policy fellow at the Institute of Race Relations (IRR).