Africa’s ‘lawless third’: duty of care

Swathes of the continent are home to people whose efforts at self-rule or traditional ways of life have challenged state attempts to deal with COVID-19

The lack of access to healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced by millions of Africans as a result of living in ungoverned, under-serviced, rebel-controlled, or poorly supported alternatively administered regions, raises a unique set of problems for governments, donor agencies, and healthcare professionals combating the novel coronavirus. The sheer scale and persistence of this problem has caused many decision makers at country and international levels to turn a blind eye to it – with the unfortunate result being the avoidance of the duty of care in this troublesome so-called “lawless third” of the continent, about 34% of the continental land mass incorporating all of Libya, half of Algeria, much of the Sahara and Sahel, northern Nigeria, the Horn and a crescent of the African Forest Belt.

However, the people living in these zones deserve equitable access to universal healthcare including adequate COVID-19 testing and treatment. These conditions are far more widespread in Africa than is usually acknowledged by the authorities, though concentrated in the Sahara, Sahel, and Forest Belt regions. As such, they are deeply marked by traditional modes of nomadic livelihood that clash directly with state attempts to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Nevertheless, there have been a variety of responses to the challenge posed by the pandemic in these regions, some of them remarkably positive. Regions that fall entirely outside the ambit of governments’ abilities to respond to the virus largely embrace those that fall under the control of separatist groups or rebels.

Regions that are under-serviced fall into three, sometimes interlinked, categories: those difficult to reach because of their remoteness or rugged terrain; poor rural areas, which under-resourced governments battle to serve, even under normal conditions; and those from which state services, including healthcare, are deliberately withheld or restricted because their populations are viewed as hostile to the central state. However, notable cases of viable alternative healthcare administrations are those of two states with contested legitimacy: the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), which occupies the eastern third of the Moroccan-ruled territory of Western Sahara, and Somaliland, a Horn of Africa republic that seceded from the north of Somalia.

Governments direct few resources, including healthcare, to remote and rural provinces because of their sparse and nomadic populations. But very low average population densities should not be taken as an indication that people do not gather, socialise and interact in significant numbers in certain zones of the Sahara and Sahel. Notably, people cluster and move around bodies of water like Lake Chad (two million people within a 100 km radius of the lake’s centre, and 13 million within a 300 km radius) and along the Nile River (a density of up to 1,165 people/km² along the river’s lower course through Egypt), as well as along the ancient trade routes that traverse the region. Of relevance to COVID-19 is the potential for viral transmission at these points and along these routes.

Also, some rural population distributions are counter-intuitive: for example, the Ouargla province of Algeria and the Tombouctou province of Mali – both remote Saharan desert regions – have high focal population distributions, meaning their rural populations are densely clustered in small settlements, ideal for COVID-19 transmission given that these settlements are linked by poorly monitored/controlled nomadic travel. The African Forest Belt – home to many rebel groups – though mostly sparsely populated, also boasts zones of dense population.

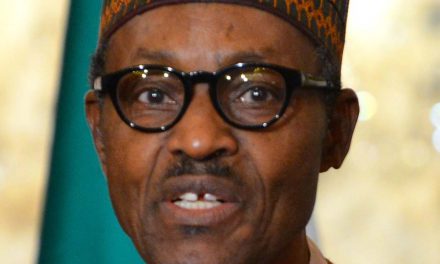

Examples include the strife-torn Lake Kivu basin in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, which has a density of over 400 people/km²: while government only controls half of the North Kivu province bordering the lake’s western shore, the rest is controlled by a patchwork of numerous guerrilla groups. Sparseness of law enforcement, resource allocation, and healthcare access has enabled rebel groups to operate with relative impunity and gives them an opportunity to legitimise themselves by offering the populace alternative services, including healthcare. But this is a rarity: insurgencies usually disrupt and overstress already fragile healthcare infrastructure. An example is northeastern Nigeria, which already had inadequate clinics and too few healthcare workers before the jihadist Boko Haram insurgency began in 2009.

This general picture of lawlessness or fragmented authority imposes some unique circumstances under which the COVID-19 pandemic has been faced across many parts of Africa, but there are instances of stable yet alternate (and thus often unrecognised) territorial authorities with aspirations to formal government and state status. At either extremity of this supposedly “stateless” third of the continent lie the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (administered by a government recognised by 40 out of 193 UN member states, 20 of which are AU members) and Somaliland (administered by a government recognised by only three UN member states, two of them AU members).

Regardless of whether the international community recognises these states, in reality they are only “unadministered” in the view of the central governments in Rabat and Mogadishu which lay claim to them; in most other respects, they fall under conventional functioning administrations, which provide healthcare to their citizens. Where diplomatic recognition does count, however, is whether these contested territories are able to access adequate COVID-19 testing, and donor or funding partner healthcare support. Pandemic statistics reported by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) derive from recognised governments only.

In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) has no official coverage of either territory by its Regional Office for Africa (AFRO). Within SADR’s zone, on 19 March, the Sahrawi government announced its implementation of COVID-19 countermeasures, including the closure of borders with friendly neighbours Algeria and Mauritania. It also created quarantine areas, and the imposition of a “stay-in-your-tent” lockdown policy. On the one hand, this indicates a seriousness by the Sahrawi authorities to exercise their duty of care, but the remoteness and relative poverty of their territory meant that when these measures were implemented, healthcare workers had “just 600 pairs of gloves and 2,000 masks for a population of between 180,000 and 200,000 people”, according to a Euronews report on 20 April.

The only reliable reporting appears to be by the UN mission in the region, MINURSO, which “maintains constant liaison with the Moroccan government, POLISARIO and Algerian government to share information and coordinate action”. Its last report, dated 5 June 2020, states: “There have been no new cases in the Tindouf Governorate (of Algeria) since 10 May and still no cases to date in the Sahrawi refugee camps or in the Territory East of the Berm”, the embankment that marks the border with Algeria. “The lone death from COVID-19 in Tindouf Governorate remains the only fatal case in MINURSO’s area of operations.” The report, however, gave no number of positive cases for the SADR-occupied portion of Western Sahara.

On the extreme east of the continent, the widely unrecognised state of Somaliland, which in 1991 broke away from Somalia – itself without a fully functional or authoritative government and state since then – has likewise posed a problem for tracking the progress of the virus, and for attempts to combat it. The internationally recognised government of Somalia in Mogadishu announced the first positive COVID-19 case on 16 March and suspended international flights in response, later followed by the suspension of domestic flights. It also tried to prevent the importation of khat (the leaf chewed for its mildly narcotic effects) as a means to limit socialising amongst people.

But Mogadishu’s grip on authority is tenuous at best. By mid- August last year it could only claim to control the capital and some of the larger cities of the south. The result has been that the official government is unable to enforce any travel restrictions by road. Also, the situation is bedevilled by drought, locust storms, flash floods, traditional contestation between six major clans, and some 2,6 million people internally displaced due to conflict. Somaliland reported its first two positive novel coronavirus cases on 31 March 2020, six days after closing its land borders and ordering incoming airline crews and passengers to be quarantined for two weeks. On 26 March, it had diverted all developmental funding into combating the pandemic.

*Accountability International is aware that the statistics that are presented to the Africa CDC or other regional/continental/global organisations on which we base our scorecard grading (for COVID-19) are not without some problems and can thus not always be taken at face value. Firstly, on a country-by- country basis, we need to have an understanding of the robustness of each country’s reporting mechanisms (are they adequately funded, comprehensive, and statistically sound?). Next, we need to recognise that in rare cases, the temptation of governments to improve their public image by under-reporting the impact of the pandemic may prove too strong: this is clearly the case with Tanzania that dangerously ceased reporting on 9 May 2020, but there may be other less obvious examples that involve under-reporting rather than a total refusal to provide data. Lastly, a pre-existing lack of data, particularly on key populations, undermines an adequate understanding of the impact of the pandemic on the most vulnerable and marginalised.*

Khat establishments were closed, mosques issued with social distancing guidelines, social gatherings outlawed, and 574 prisoners pardoned and released, but the crucial lifeline of flights to Ethiopia was maintained. To date, the Africa CDC’s figures have not differentiated between separatist Somaliland and Somalia (including Puntland), with 2,860 positive cases of whom 90 had died as of 25 June 2020, although it appears Mogadishu is counting Somaliland in its reporting to the Africa CDC and WHO. Somaliland separately reported on the same date a total of 681 cases of whom 28 had died. On 15 July, Somalia reported 3,083 cases of whom 93 had died, with Somaliland the following day reporting 807 cases of whom 29 had died.

Lacking its own testing facilities, the breakaway state has been sending abroad to get test results. COVID-19 aid is being sent via Mogadishu – which politically and practically undermines Hargeisa (the Somaliland capital): in late April, the European Union (EU) donated €27 million to Somalia, of which €10 million was officially earmarked for Somaliland. Yet it was subsequently reported that Somaliland had been entirely cut out of the aid. On 23 June, Hargeisa announced the lifting of all anti-COVID-19 measures – though social distancing and the quarantining of virus-positive people entering the country remained in force.

The government did not give reasons for reopening the country, but it is likely that it could no longer bear an economic shutdown without external aid. Lastly, we must deal with the fact that some regions in many African countries are deliberately under serviced by central governments because of their perceived hostility to the incumbent political leadership. Such pre-existing ethnicised healthcare access inequalities are only amplified under COVID-19. For example, in Burundi, the aftermath of the genocidal civil war between a Tutsi-dominated army and Hutu rebel groups from 1993-2005 has seen the authorities enforce 60% Hutu/40% Tutsi ethnic quotas on the staffing of foreign NGOs, including in the healthcare sector.

Human Rights Watch noted: “On 1 October 2018, authorities suspended the activities of foreign non-governmental organisations (NGOs) for three months to force them to re-register, including new documentation stating the ethnicity of their Burundian employees.” The disruption put many healthcare projects months behind schedule, while some NGOs, wary of how the ethnicity data might be misused, exited the country entirely – all of which has undermined Burundi’s COVID-19 response. On 12 May 2020, the Burundian government declared persona non grata the WHO’s country director and some of its health experts who were critical of underreporting of data on the pandemic.

On 10 June, President Pierre Nkurunziza, who had refused to take strong measures against COIVID-19, died of a heart attack rumoured to have been brought on by the virus. Denial of healthcare in remote borderlands is most often practised against migrants, refugees and other non-citizens, even under COVID-19 quarantine. An example of this is from Ethiopia, where a Reliefweb update on the pandemic warned that “Internally Displaced persons (IDPs) living in congested and unsanitary collective centres, spontaneous and planned sites, rental accommodations or shared shelters with relatives in host communities are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19.”

Complicating the issue is that most undocumented migrants, including asylum seekers, cross international borders often knowing nothing about the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the UN’s International Organisation for Migration (IOM) reported that just over half of all migrants attempting the dangerous crossing into the Gulf states from Somalia via war-torn Yemen had not heard of COVID-19. An urgent starting point is for all armed groups – state or rebel – to allow international healthcare agencies to do their work in remote and conflict torn areas unhindered. In addition, the international community needs to immediately put human lives above diplomatic considerations and provide direct assistance to SADR, Somaliland, and any other contested regions where the rulers of which, regardless of their official status, have demonstrated their administrative capacity and resolve to fight the pandemic.

Lastly, African administrations and their international supporters must pay significant attention to the most vulnerable population groups languishing in poor, remote, and under-serviced areas across the continent, key populations most threatened by the novel coronavirus. Only by adhering to universal healthcare commitments can we advance equitable access to all, establishing a legacy of robust care well after the current crisis is over.

Michael Schmidt is a Johannesburg-based investigative journalist who hasworked in 49 countries on six continents. His main focus areas as an Africa correspondent for leading mainstream journals are emerging and high-end technologies, political developments, conflict resolution and transitional justice, and on the continent’s maritime and littoral spaces.