Lessons and the way forward

On 5 March 2021, South Africa reached an important milestone: 100 000 vaccinations were administered to healthcare workers. Exactly a year to the day after South Africa recorded its first case of the coronavirus, it is a bittersweet triumph, but in these uncertain times, a triumph nonetheless.

Thus far, official figures confirm more than 1.5 million cases of COVID-19, and over 50,000 deaths. Unofficially, the number of true infections may exceed 10 million. A recent South African Medical Research Council report states a more realistic number of COVID-19 deaths may be closer to 130 000. While we may never know the true figures, citizens hope that the government will formulate and implement measures which will strengthen South Africa’s national coronavirus response.

The arrival of several lifesaving vaccines into the pandemic space has been seen as a timely miracle. Some estimates conclude that without the vaccines, the pandemic threatens to take more than 150 million lives globally. However, what has also become apparent is that expecting vaccines alone to rid us of the pandemic may be a mistake. Scientists have predicted the coronavirus may remain with us for several years to come, so finding a solution to the pandemic will require a global collective effort.

To date, more than 320 million doses of various coronavirus vaccines have been administered in over 118 countries worldwide. The latest rate was roughly 8.25 million doses a day on average. This achievement is humanity’s silver living in this dark, uncertain period brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, with most silver linings, there are grumbling dark clouds waiting to roll in and exploit any laxity. This is particularly true regarding our national-level South African coronavirus response.

To adequately address and take heed of lessons learned over the last year, it is important to take stock of where the global and national coronavirus response stands. When COVID-19 first struck, governments were caught by surprise. Now it is imperative to formulate policies that pre-emptively plan the way forward. Moving into the vaccination phase of the fight against the pandemic, certain factors must be taken into account and prioritised so as not to lose any positive momentum going forward. It is clear from the literature that we should expect to have some degree of COVID-19 in our lives in the future. The following items should therefore be considered and prioritised in policy formulation going forward, so as to reinforce our collective national response fight against the pandemic:

Current Situation and State of Affairs

- Global Vaccination: will it be possible to vaccinate all of the almost 8 billion people on earth, or a large enough portion of that population, in time to avoid the formations of variant strains? Aside from the developed world, the majority of the developing world has yet to start its vaccination programmes. If they are not vaccinated in time, will they be hosts for new strains of the virus?

- New viral variants: While vaccines are making the coronavirus less infectious, and are protecting people against death, the advent of new viral variants is a concern. The South African, Brazilian (P1) and Kent (UK) strains vary in their transmissibility. Of concern is the discovery that these new strains have shown they are up to 70% more infectious than the standard strain.

- Vaccine refusal: South Africa plans to vaccinate 67% of the population against the coronavirus before the end of 2021, a figure of roughly 40 million people. But a recent global survey highlighted that only 53% of South African respondents stated that they would agree to be vaccinated. South Africa is lagging far behind the global curve, not only in the acquisition of vaccines, but more importantly in perceptions around the effectiveness and safety of immunisations. These concerns must be alleviated if our vaccine rollout and efforts to curb the pandemic are to be successful.

Mixed Messages

At the end of February, Health Minister Zweli Mkhize stated the country aims to vaccinate around 1.1 million people against COVID-19 by the end of March. However, earlier this week the Deputy Director General at the Department of Health, Dr Anban Pillay, stated Phase 2 of South Africa’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout could begin at the end of April or early May. Also this past week, however, Deputy Health Minister Joe Phaahla raised some concern when he alluded to the fact that there are not enough vaccines currently available to meet the demands of Phase 1.

Additionally, almost three months ago, certain government officials were lecturing South Africans to the effect that vaccines are no “silver bullet”, which was irresponsible, as South Africa must prioritise inoculating as many people as possible to curb the threat and challenges experienced over the past year.

In normal circumstances, a month or so may not make a big difference, but given the unpredictability of the fast-mutating COVID-19 strains, even a few days could cost the lives of many more South Africans. These mixed messages exacerbate the already high levels of mental stress brought on by the pandemic.

A World Health Organization (WHO) survey has found that the pandemic is creating an increasing demand for mental health services, triggered by bereavement, isolation, loss of income and fear. Measures should be implemented to ensure mixed messaging is limited, so as to not burden an already stressed healthcare system battling with growing social ills brought on by the pandemic, such as family breakdown, alcohol abuse and a rise in alcohol-related deaths.

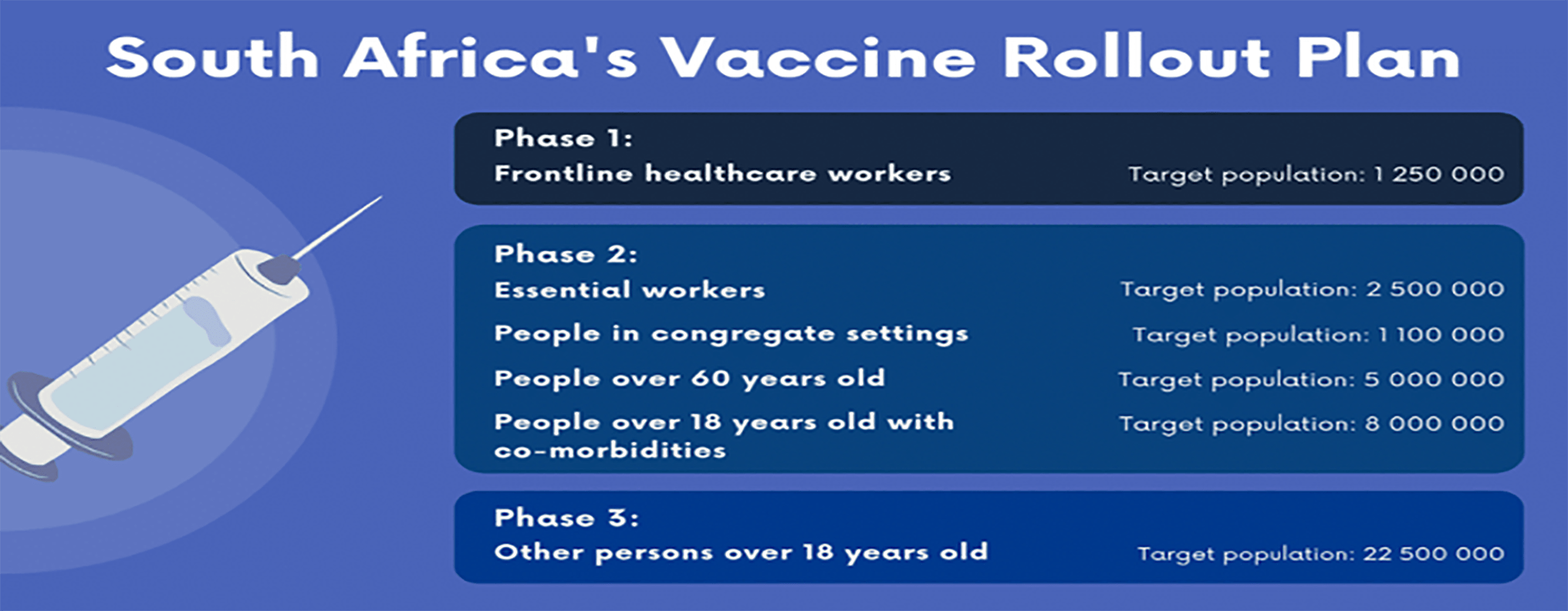

South Africa’s COVID-19 vaccine roll-out plan. National Department of Health

Vaccine Rollout

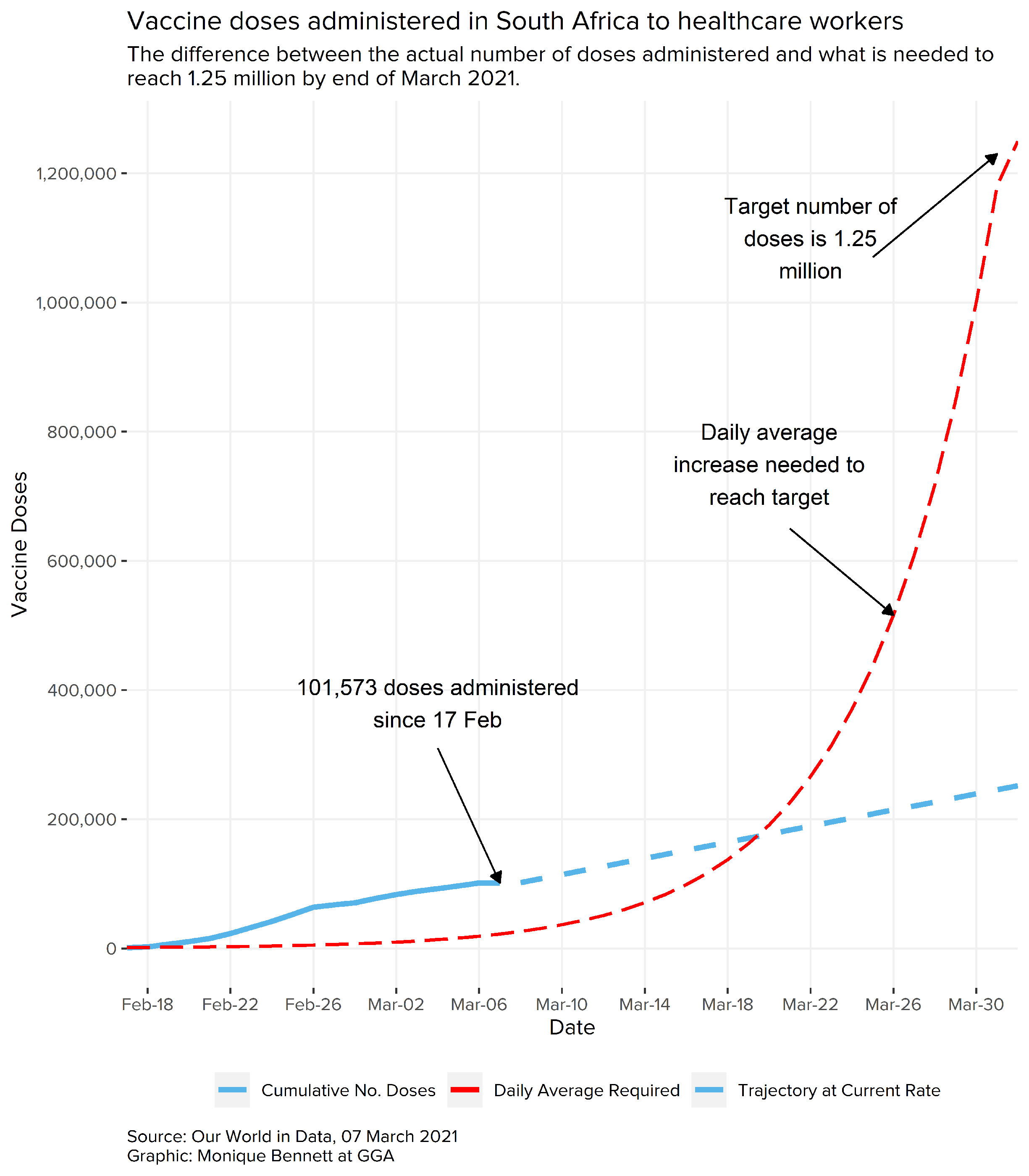

While we should celebrate having already vaccinated over 100 000 healthcare workers, it would be remiss of me to fail to highlight concerns about the vaccination rate. At present, the daily roll-out rate sits at about 6250 doses per day (between 17 Feb and 5 March). Meeting the initially proposed target of 1.25 million doses by the end of March is highly unlikely. If the target is to be met, it would require averaging at least 44 230 doses of the vaccine every day over the next 26 days.

Encouragingly, during President Cyril Ramaphosa’s address on 28 February, he stated that all provinces have established vaccination sites and have put in place plans for the expansion of the programme going forward. He also stated the number of sites that will be available for vaccination will be expanded from 17 to 49. Of these 49, 32 will be located in public hospitals and 17 in private hospitals. This should provide both optimism and a sense of relief that the number of vaccines administered should increase dramatically going forward.

Vaccine Supply

Vaccine Supply

During President Ramaphosa’s 28 February address he specified the following regarding the procurement and supply of vaccines:

- An additional 80,000 doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine were scheduled to arrive in the country which will (hopefully) steadily increase the number of doses administered each day.

- An agreement was signed with Johnson & Johnson to secure 11 million doses. Of these doses, 2.8 million doses will be delivered in the second quarter and the rest spread throughout the year.

- 20 million doses were secured from Pfizer, which will be delivered from the second quarter.

- 12 million doses were secured from the COVAX facility, with government finalising South Africa’s dose allocation from the African Union.

He also assured the nation: “We are in constant contact with various other vaccine manufacturers to ensure that we have the necessary quantities of vaccines when we need them.”

Potential Third Wave

The Health Minister recently explained there was no clear model for predicting exactly when South Africa may experience a third wave of COVID-19 infections, but there are strong indications it could take place in late April or early May. Several analysts have predicted it may occur during the Easter break where there will be large numbers of the population traveling and attending events.

Some actuaries have calculated a third wave will occur if followed by super-spreader events, coupled with reinfections during the Easter period. Such a combination could increase expected deaths in South Africa to 92 500.

It is important to remember and reiterate that society’s behaviour is the key determining factor in whether policy measures for curbing the pandemic will be successful or not.

Herd Immunity

- In the worst case, we do not actively perform physical distancing or enact other measures such as mask-wearing and hand sanitising to slow the spread of the coronavirus. The virus will continue to infect thousands more people in a matter of a few months. This will result in our hospitals being overwhelmed and lead to high death rates.

- In the best case, we maintain current levels of infection – or even reduce these levels – until the South African vaccine rollout is accessible to all.

- The most likely case is somewhere in the middle, where infection rates rise and fall over time; we may relax social distancing measures when numbers of infections fall, and then may need to re-implement these measures as numbers increase again. This calls for a more pre-emptive approach from government. While waiting for the vaccine to be more inclusive of the population, children could be infected before they can be vaccinated, or adults may be infected after their immunity wanes. However, the silver lining is that it is unlikely in the long term that the virus will have the explosive spread we have become accustomed to, because much of the population will be immune in the future.

- Also, in tandem with South Africa’s COVID-19 national response, it is necessary that the neighbouring countries also attain some degree of herd immunity. If not, we may expect an influx of infections to continue streaming in from across the borders.

A Brave New Corona World

Even once vaccination targets are achieved, life as we knew it may not return to the normal we were accustomed to and took for granted. Medical advances are seeing the tweaking of vaccines to provide a more all-encompassing protection. These tweaks may provide further protection against the arrival of new variants. In a perfect world, according to The Economist: “the best outcome would be for a combination of acquired immunity, regular booster jabs of tweaked vaccines and a menu of therapies to ensure that COVID-19 need rarely be life-threatening. But that outcome is not guaranteed.”

But as we have seen throughout our COVID-19 journey, medicine alone may not be able to prevent lethal outbreaks of the pandemic. Thus, to complement the medical advances, responsible social behaviour becomes that much more important. Individuals and communities must embrace a future that may necessitate continued mask wearing, washing of hands and sanitising as the norm for our daily existence. Other possible measures being considered by several countries is the need for vaccine passports and mandatory restrictions in crowded spaces. Vulnerable people will have to maintain great vigilance in order to avoid becoming infected.

To this end, it is apparent that the new phase of addressing the COVID-19 pandemic will require all governments to procure and administer vaccines in a timely manner to achieve some level of herd immunity. Trust deficits brought on by mixed messaging and the harsh consequences of sometimes poorly formulated lockdowns must be redressed. As argued by Professor Geo Quinot: “Thus, apart from the constitutional values of good public governance, which require high levels of transparency, such transparency in government’s vaccination programme is essential for the very success of the programme, since without transparency there cannot be public trust.” And without public trust, responsible social behaviour will wane, jeopardising our efforts for a successful national coronavirus response.

Craig Moffat, PhD is the Head of Programme: Governance Delivery and Impact for Good Governance Africa. He has more than 17 years of practical experience working for government institutions and multilateral organisations. He was previously employed by the South African Foreign Service, where he worked extensively at identifying and analysing security threats towards South Africa as well as the southern Africa region. Previously, he was the political advisor for the Pretoria Regional Delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. He holds a PhD in Political Science from Stellenbosch University.