Last month, President Cyril Ramaphosa signed the Electricity Regulation Amendment (ERA) Act into law, marking one of the most significant and potentially transformative milestones for South Africa’s electricity sector.

The Act makes provision, and opens pathways, for increased competition, promises reduced energy costs, encourages investment in new generation capacity to secure energy supply, and establishes an independent transmission company that would oversee the national grid. The company is a “transmission systems operator” (TSO) called The National Transmission Company of SA (NTSCA). Additionally, the Act imposes heavy penalties for damaging or sabotaging infrastructure.

Despite these ambitious goals, the Act falls short of tackling the deep-rooted financial instability of Eskom, South Africa’s electricity utility company, and the mounting debt of municipalities. It leaves these critical issues largely unaddressed, raising concerns about the viability of its long-term impact. Moreover, the introduction of new electricity providers under a TSO raises concerns about how municipalities and Eskom will navigate and adapt to this shifting landscape, given their existing financial struggles.

Earlier this month, Eskom, formally seized and attached four bank accounts belonging to the Emfuleni Local Municipality to recover R8 billion in outstanding debt. This is a result of the municipality defaulting on debt repayments and failing to comply with the requirements of the National Treasury debt relief programme, which was announced last year.

Emfuleni, one of South Africa’s most heavily indebted and mismanaged municipalities, owed R8 billion in arrears – amounting to 10% of the total outstanding debt owed by municipalities to Eskom. In our Governance Performance Index, Emfuleni came 17th of 19 secondary cities, and 151st out of 205 local municipalities ranked. Yet, municipalities’ exorbitant debt is not an isolated incident but rather highlights a broader challenge faced by local governments and Eskom in addressing unsustainably high municipal debt levels.

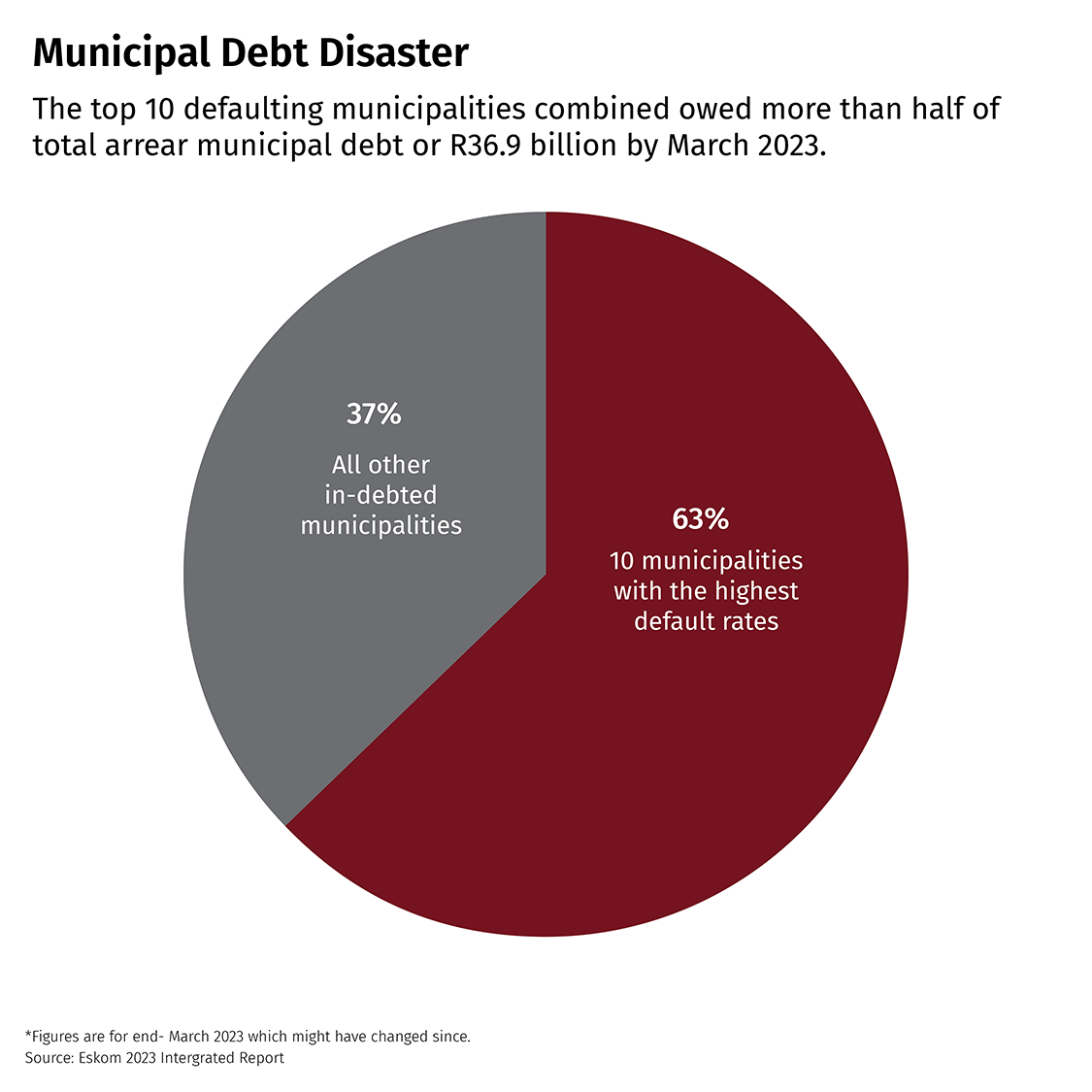

Of South Africa’s 248 municipalities that Eskom supplies, more than half had overdue accounts totalling R58.5 billion by March 2023, with the majority of debt due to Eskom concentrated in 10 municipalities.

In its latest Integrated Report 2023, Eskom identified the most debt-burdened municipalities to be; Emalahleni Local Municipality, Maluti-a-Phofung Local Municipality, Emfuleni Local Municipality, Matjhabeng Local Municipality and Govan Mbeki Local Municipality. While the top 20 defaulting municipalities reportedly owed arrears amounting to around R45 billion at year end (or 78% of total arrears at the municipal level).

Several factors and challenges have contributed to the current municipal debt spiral. Poor capacity, combined with limited skills and resources, compounds longstanding inefficiencies between municipalities and Eskom, such as a lack of prioritising debt repayments by municipalities and mismanaging consumer accounts. Additionally, there are critical gaps in legislation that could help manage or prevent this debt, exacerbating the issue.

In a media address, Minister of Electricity and Energy, Dr Kgosientsho Ramokgopa, added that “failure to collect revenue, illegal connections and a decline in sales of electricity because of theft and load-shedding had worsened the ability of municipalities to pay their debt to Eskom”.

The escalating municipal debt burden has severe implications for both Eskom and consumers. For consumers and residents in defaulting municipalities, the financial strain on municipalities often translates into higher tariffs, service disruptions in the form of “load reduction”, poor maintenance of electricity infrastructure and general public service decline. Moreover, the national electricity regulator for SA (NERSA) recently approved an 18.65% tariff hike for the 2023–24 year but limited that to 10% for low-income households. For Eskom, municipal failure to pay means reduced cash flow and limited ability to reduce operating costs, invest in its own infrastructure, and manage its own debt. This will likely also lead to increased borrowing from Treasury, creating a vicious cycle.

Efforts to circumvent the issue, such as the Municipal Debt Relief Programme announced by the Treasury in May 2023, have aimed to improve the utility’s balance sheet and facilitate proposals for Eskom to write off certain debt under strict conditions. By January 2024, 70 municipalities had been approved to join the Eskom Municipal Debt Relief Support Programme. Yet, despite these efforts, municipal debt has continued to surge, while constrained municipalities continue to default on payments, suggesting that the government’s current approaches to rescuing Eskom’s debt lack precision and are not showing significant improvement yet.

The mounting arrears add yet another layer of complexity to Eskom’s already overwhelming challenges. Between March and September 2024, outstanding municipal arrears increased by 4 billion over 6 months to R82 billion, according to the latest figures from an Eskom media statement. This escalating debt not only continues to strain the utility’s financial resources; it compounds the myriad issues that Eskom and the national government have had to navigate, including its public utilities’ own significant debt burden. As municipalities continue to grapple with their fiscal crises, the ripple effects threaten to undermine Eskom’s stability, hinder reliable electricity supply, and exacerbate the ongoing energy crisis in South Africa.

The government has introduced numerous strategies to tackle the country’s energy crisis, from reshuffling Eskom’s leadership and providing massive bailouts to forming the National Energy Crisis Committee, which engages the private sector. Most recently, it has turned to legislative reform in a bid to drive lasting change.

However, according to president Bheki Stofile of the SA Local Government Association (SALGA), South Africa’s electricity policies and legislation have often created significant challenges for municipalities, making it increasingly difficult for them to effectively fulfil their mandate. In addition, municipalities have a critical role in successfully transitioning to a more stable energy sector, but the lack of finances and capacity to respond to these responsibilities remains a significant challenge. The other major concern is that many of the provisions outlined in the Amendment Act effectively dilute both municipalities and Eskom’s role in generating and distributing electricity, further compromising revenue flows.

In a best-case scenario, as new electricity supplies enter the market, Eskom could benefit from reduced pressure to meet demand and supply at a national level. This diversification of supply would enable Eskom to focus on improving its capacity, reducing operational costs and recovering its finances. For municipalities, a successful implementation of the Act could see more affordable tariffs and reduce its reliance on Eskom.

For consumers, increased competition among electricity providers could mean lower energy costs. More providers entering the market could also lead to improved service delivery and a more reliable power supply as energy generation becomes more diversified. However, this will require substantial and rapid investment in transmission grid reconfiguration to provide optimal ingestion points for renewable energy projects.

In a worst-case scenario, however, Eskom will have to navigate the loss of the bulk of its revenue base to competitors, which could burden them even further. If Eskom cannot adapt quickly enough, it could spiral further into debt, requiring additional government bailouts or restructuring. For debt-burdened municipalities, already grappling with financial mismanagement, if they cannot afford and honour agreements and commitments made, they also risk worsening their financial crises, leading to even more volatility. Moreover, misalignment between municipal and TSO priorities could create gaps in service delivery, compounding the instability of local grids. In this scenario, the cost burden ultimately falls on consumers and residents, who risk higher tariffs and service delivery failure.

If the national government seriously intends to achieve the outcomes laid out in the Amendment Act, it must also efficiently address legislative gaps and ongoing challenges related to fiscal instability already burdening the country’s energy sector. It must do so transparently while ensuring accountability to avoid further trust erosion in local governance and infrastructure.

Mischka Moosa is a researcher and data journalist in the Natural Resource Governance and Climate Change programme at Good Governance Africa (GGA). She holds a Bachelor of Social Science (Honours) in Political Science from the University of Cape Town (UCT). Her focus is on advancing justice, sustainable development, and transformative governance across the African continent, with particular interest in the intersections of environmental policy, resource management, and social development.