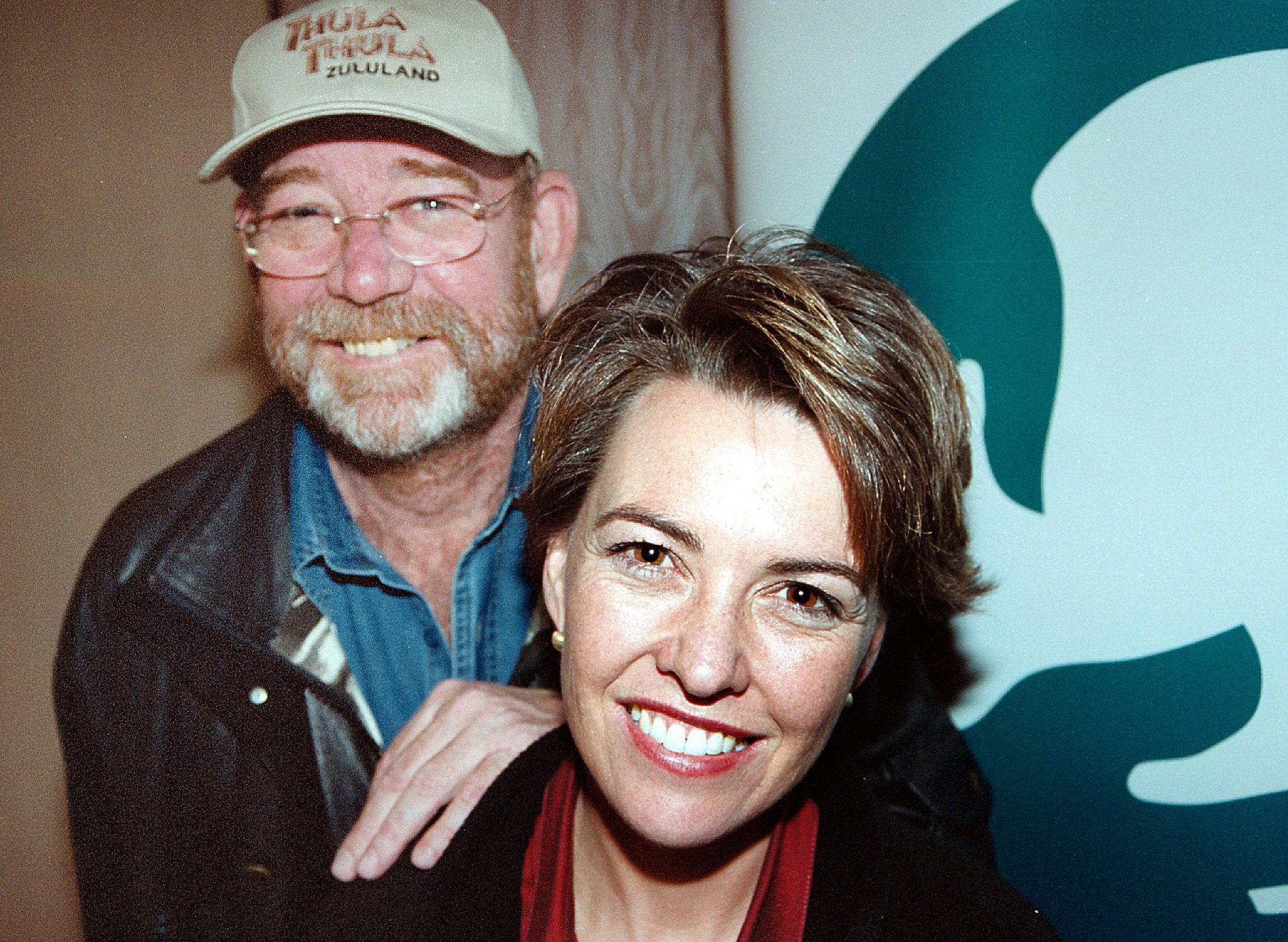

In 1999, South African conservationist Lawrence Anthony was asked to accept a herd of seven abused, traumatised and troubled elephants on his game reserve in KwaZulu-Natal. With no scientific training and no experience looking after elephants, Anthony cared for them so much that when he died of a heart attack in 2012, the elephants sensed it and travelled on their own for hours to his house.

The elephants had not visited the house for years. For two days, they stood around the house mourning him before going back to the wild. Since then, every year on the anniversary of his death, the elephants make the pilgrimage to his grave to mourn him.

In their insightful article, “Towards a Caring Economy”, Tania Singer and Dennis J Snower discuss the numerous global challenges that humanity fails to adequately address. They write that “from climate change to resource depletion, from banking crises to sovereign debt crises, our economies are not overcoming the scourge of poverty or the inadequate provision of collective goods.”

Furthermore, they elaborate on the societal impacts, stating that “our societies are increasingly fragmented, perceived loneliness as well as stress-related diseases such as burnout are increasing, and our governance structures are inadequate for the problems we face.”

These observations underscore the pressing need for a significant shift towards a more caring and responsive economic and governance system to navigate the rapid technological changes affecting our ways of working and living.

Why, when we as humans have so much capacity for caring, consciousness and creativity, has our world shown so much cruelty, insensitivity, and destructiveness, asks Riane Eisler in her book, The Real Wealth of Nations: Creating a Caring Economy.

Why indeed, when our leaders preside over so many resources for delivering quality services, controlling crime and corruption, and holding the guilty to account under the rule of law, have our countries seen so much hardship, poverty, and impunity?

Looking after number one

Singer and Snower say that much of our political and economic thinking remains based on a conception of human nature known as homo economicus. According to this conception, humans are self-centred, materialistic, and rationally operating individualistic agents. Apparently, this selfishness can be traced to when we were babies.

In her book, The Selfish Society: How We All Forgot to Love One Another and Made Money Instead, Sue Gerhardt says human-centeredness best expresses itself or starts in our “babyhood experiences”.

Harvard developmental psychologist Howard Gardner writes that “the young child is totally egocentric” while philosopher Ken Wilber expands our understanding by outlining three stages of human development: egocentrism (self-centeredness), ethnocentrism (focus on the closest people), and world centrism.

This means that for a normal human being to contribute positively to society, they need to outgrow egocentrism and ethnocentrism and embrace world-centrism, which is more positive.

What is disturbing, according to Gerhardt, is that sadly, these babyhood experiences are not just an issue for individuals “but also matter to society. Particularly in the current economic crisis … I believe that it is important to understand the connections between our infancies and the kind of world we create”.

‘Age of selfishness’

This led columnist and academic Martin Jacques to conclude that our society has been hijacked by the “credo of self” and as such, we are living in the age of selfishness.

Gerhardt defines selfishness as “the pursuit of self-interest without regard for others’ needs or interests”. If the crass corruption in our society proves anything, it must be that the self-centred and self-serving consciousness permeates not just the highest echelons of our societies, but also the upcoming business and political leaders.

It means that we have an abundance of infantile leadership cores in key positions of power, both in politics and business. This is a class of leadership that has not evolved from the egocentrism of its infancy.

Like infants, says Gerhardt, they “have not yet learned conventional rules and roles… They cannot yet take on the role of others and thus begin to develop genuine care and compassion. They therefore remain egocentric, selfish, narcissistic, and so on. Their feelings and morals are still heavily centred on their own impulses, physiological needs, and instinctual discharges.”

Self-serving leadership is a typical example of destructive leadership that has negative effects on its subordinates and the organisation. Our present history is characterised by the shameless and even violent accumulation of wealth at the expense of the needs of the majority. This cancer has insidiously mesmerised our body politics, even infecting the younger, upcoming leaders.

What can be done about this, and how can we have leaders who, like Lawrence Anthony, love and care for not just animals but, more importantly, people?

Political and leadership education

Writing in the Journal of Pan African Studies in 2014, Dr Nana Adu-Pipim Boaduo argues that “political education is very crucial if democracy is to mature in African countries and contribute towards achieving democracy and credible free and fair electoral process that would change African politics dramatically.”

To achieve this important aim, she believes that all categories of teachers at all levels of African institutions should be provided with both fundamental and advanced political education during their studies in higher institutions of learning to be able to propagate the niceties of political education to advance and make democracy successfully implemented in African countries.

I disagree with her on three points. The first one is her belief that political education should be confined to the education system from primary to tertiary levels. She herself states correctly that “there is evidence that classroom teachers often corrupt a curriculum by hijacking it to promote their ideologies since most teachers who are politically oriented have their own view of the political ideology that they support.”

Given this, to avoid ideological fracturing and conflicts in schools, we need to make sure that participants do so voluntarily and willingly.

The second issue is that this good governance education should not be driven by the government but by civil society and implemented across all areas of the community. Derek Heater writes that “democracy is a sham or, at best, a sort of political yo-yo unless the electorate plays an effective and considered part in determining the nature of the government.”

This means that, whatever the solutions to governance issues, citizens must be at the core. This is because “politics governs our lives in society and affects many aspects of our lives. It regulates what we can read, say and watch, tells us when and how to pay taxes, and administers everything from driving privileges to business activity.”

In other words, politics presides over us literally from birth until death. Currently, it is the political parties that run political education programmes, narrowly focused on specific ideological positions. But a programme of this magnitude and importance cannot be left to politicians; it must be led by civil society.

Impartial Governance vs ideology and prejudice

The third area is the content of the curriculum. I believe that for this good governance education, based on democratic principles, to work for the citizens, it must be emptied of its outdated party-political ideological content and underpinnings and include good governance principles, including ubuntu, servant leadership, selflessness, civic education and quality customer service.

Good governance principles include participation, consensus-orientedness, accountability, transparency, responsiveness, effectiveness and efficiency, equity and inclusiveness, and the rule of law.

Although the ideal governance setup is democracy, this model can be applied to any system of governance, whether it be a democratic or traditional authority setup. Africa must free itself to pick and choose governance aspects that can work best in our situation.

We need leadership characterised by integrity, accountability, and a true dedication to the well-being of everyone, as well as a movement led by civil society for comprehensive governance education across nations, a campaign that equips citizens and fosters the development of ethical leaders.

The critical need for altruistic leadership in South Africa as it nears the crucial elections on 29 May 2024 cannot be emphasised enough. The destiny of the nation relies on the selection of leaders who embody selflessness and a profound dedication to good governance principles.

As John Maxwell said, “everything stands or falls on leadership”.

In this defining moment, the future of South Africa rests with leaders who possess the courage to prioritise the collective good, leaders capable of reshaping the political terrain through a visionary and principled approach.

The country’s future depends on leaders who understand the power of love and care in governance, as demonstrated by the gratitude and loyalty of a herd of elephants to a compassionate caretaker in KwaZulu-Natal in 1999.

- This article first appeared in Daily Maverick.

Lonwabo Patrick Kulati is the Chief Executive Officer of Good Governance Africa’s (GGA) Southern Africa Regional Office (SARO). He has a strong history of leading international NGOs and driving organisational growth, effectiveness and profitability. He also has expertise in strategy development and execution, leadership coaching, fund development, stakeholder management, advocacy and partnership cultivation. Patrick is also a published author of "A Gap in the Cloud," providing valuable insights and inspiration on personal and leadership resilience. He holds a Master’s degree in Public Administration from the University of Stellenbosch.