African dynasties: a common phenomenon

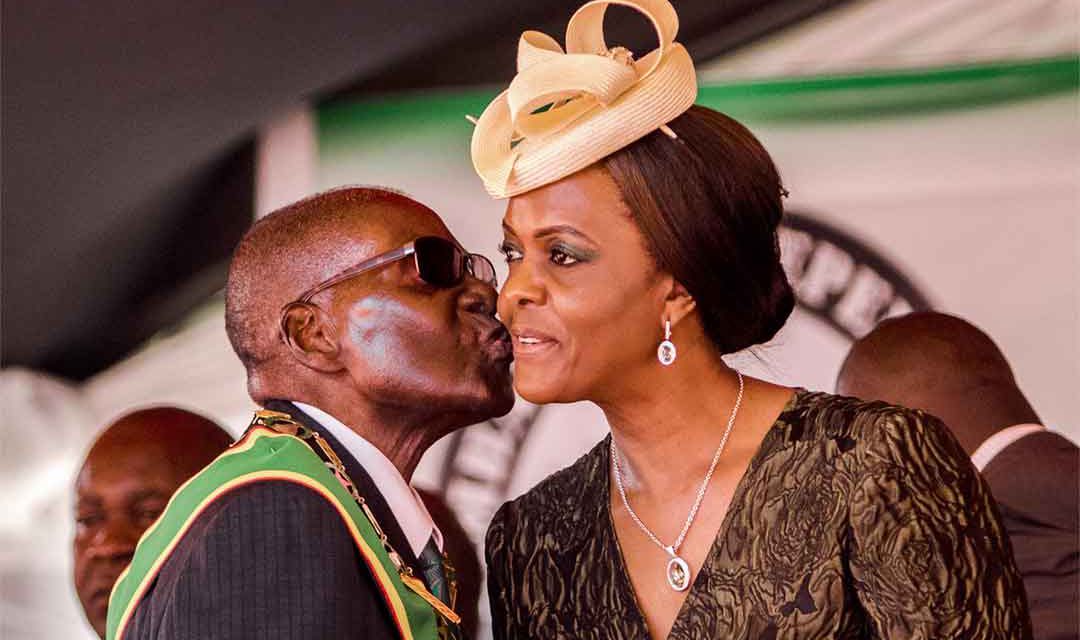

Grace Mugabe with her husband and Zimbabwe’s former president, Robert Mugabe Photo: Graeme Williams

By Marcel Gascón Barberá

Political dynasties have not been an uncommon phenomenon in post-colonial Africa. In Togo and Gabon, two families have been ruling for decades. Hereditary transmission of power is also a reality in the DRC, where Joseph Kabila succeeded his father after the latter’s assassination, and where power of a sort has been transferred from Étienne Tshisekedi, a former leader of the opposition, to his son Félix, now president. Two of the five presidents of Botswana’s history hail from the Khama family, and the current Kenyan president is the son of the country’s first post-colonial leader.

Many African leaders have been tempted to establish a dynasty at the highest political level. The successful attempts, it might be argued, have been founded, at least in part, on the strong personalities of those involved. In other cases, such attempts have been less successful – and paradoxically, for the same reason.

In November 2018, Kenyan daily The Standard ran the following headline, reflecting an unusually candid statement made by the opposition leader, Raila Odinga: “We are not princes”. His use of the first-person plural included Odinga’s rival, President Uhuru Kenyatta. In the article, Odinga vehemently denied that either he or Kenyatta owed their careers to their fathers: “Nobody has elected Uhuru because he is the son of Kenyatta,” he told the newspaper. “Nobody votes for Raila Odinga because he is the son of Oginga Odinga”.

In this way, the opposition leader absolved himself and his opponent of the odious charge of having been born with a silver spoon in their mouths. To bolster this claim, he called himself a “hustler” politician, and cleared the current president of the same accusation by reminding readers of the humble origins of Kenyatta senior. Odinga acted as Kenyatta’s deputy president until a fall-out between them prompted Odinga to start his own opposition party. Uhuru Kenyatta, meanwhile, is the son of the first independent Kenyan leader, freedom fighter Jomo Kenyatta, who worked as a house man, cook, carpenter and clerk during his youth. Many observers would argue that, in fact, Uhuru and Raila have spent most of their political lives reproducing the ongoing quarrel between their fathers.

When the president, Daniel Arap Moi, appointed a young and inexperienced Uhuru the ruling party’s presidential candidate in 2002, Raila protested and refused to support Kenyatta, who went on to lose the election against Mwai Kibaki. Raila and Uhuru found themselves in opposing camps again during the bloody 2007-2008 elections, when Kenyatta championed Kibaki’s re-election against Odinga’s candidacy. In 2013, Uhuru finally won his first presidential term, after defeating Raila. Four years later, Kenyatta was re-elected, having again defeated Odinga for the presidential vote.

Despite Odinga’s protestations, Kenyatta and Odinga clearly do owe much of their political influence to who their parents were. But he also had a point: their road to the top has been far from smooth and both have experienced electoral defeats and years in opposition. In this respect, the Kenyatta and Odinga dynasties are more similar to those that have intermittently dominated the political landscape in certain countries in Asia and the Americas than the families that distribute state power among their members in some North Korean-style African dictatorships. Kenyatta and Odinga’s successes are not based on the direct influence of their fathers; if their privilege gained them a place at the starting line, they still had to run the race.

In Zimbabwe, meanwhile, a different attempt at establishing a dynasty has recently played itself out. A few days before Zimbabwe’s former president, Robert Mugabe’s, forced resignation in 2017, when the army turned against him, a demonstrator displayed a placard with the following message on it: “Power is not sexually transmitted”. The aged leader was a target of popular anger, but it is arguable that his wife, Grace, was even more so. “Gucci Grace” – as she is known for her love of luxury – was preparing to take office as the country’s vice president, which would have made her a shoo-in as her husband’s successor.

The former vice president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, had been a victim in Grace’s ascension. The ZANU-PF stalwart was dismissed after the first lady accused him of promoting “factionalism”. Mnangagwa told his former boss from exile that Zimbabwe was not his personal property to do with as he pleased. Invoking his struggle credentials, Mnangagwa then demanded that the party cadres choose between him and Grace. The high command of the army spoke: the president had gone too far in his attempt to impose his wife over his old comrades, and it was time for him to go.

Grace was born in South Africa, to Zimbabwean migrant parents in Benoni, a South African working-class town that has also given the world Charlize Theron and Princess Charlene of Monaco. She met Mugabe while working as a typist at State House, and they started a romance that led Grace to become first lady and heiress apparent to Zimbabwe’s top office. But in the eyes of Harare’s ruling class, Grace – who is 41 years younger than her husband and thus also much younger than the gerontocracy that governs Zimbabwe – lacked any legitimacy. The country’s politics are dominated by former guerrilla fighters with a long history of political militancy. Grace, meanwhile, owed all her public career to her husband. Her acceptance was not aided by the nouveau riche insolence which she displayed while enjoying the fruits of corruption.

The Mugabes’ attempt to install a dynasty cost them power, but – so far, at any rate – they haven’t been persecuted. Mnangagwa has instead allowed the family to continue the lavish lifestyle they enjoyed while in office. Nevertheless, the Mugabes still attract attention, like a deposed royal family tolerated by a newly installed Republican government. The former president’s colourful political statements still entertain the public. Meanwhile, his wife remains a headline-maker in the gossip columns, a controversial, glamorous celebrity who fascinates many in her country and who is also hated by them.

Mugabe is treated as an old patriarch who lost his mind because of a younger woman, while the protections afforded to Grace are probably more in deference to her husband than any expression of love for her. Responding to an extradition request from South Africa, where Grace is accused of assault, the Mnangagwa government refused to hand over the former first lady. “An attack on Grace Mugabe is an attack on the former president,” it said in a statement, adding that the former president was a “liberation icon” whose “misery is undesirable to us”. It remains to be seen if Grace will be treated in the same way once the liberation icon is gone.

In South Africa, meanwhile, in 2017, outgoing African Union chairperson Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma returned to her country to contest for the top job of the ruling ANC before her former husband, South African president Jacob Zuma left office, with many commentators seeing this as an attempt to install her as the country’s next president. Dlamini-Zuma’s main source of support came from Zuma himself, to whom she had been married between 1972 and 1998. At the time, Zuma was cornered by corruption accusations and was also believed to control lucrative family business interests that needed state protection. He needed a successor who would protect him. Dlamini-Zuma’s loyalty to her ex-husband had survived 16 years of marriage and a divorce. Who could be more trustworthy than the mother of four of his children?

And indeed, Dlamini-Zuma adopted the “white monopoly capital” and “radical economic transformation” narratives her ex-husband had used to cover up his scandals, and dismissed protest marches against Zuma as manifestations of white privilege. For his part, Zuma made clear his support of Dlamini-Zuma, highlighting her political stature and managerial capacity beyond her status as the president’s ex-wife. Dlamini-Zuma has a long political career based on her own merits. Added to which, pro-Zuma political operators introduced a feminist argument in favour of Dlamini-Zuma’s candidature – though it seemed somewhat unnatural for a bunch of die-hard Zuma loyalists to wave the feminist flag. Twelve years before, Zuma’s propaganda machine had vilified a woman who accused him of rape – to the extent the woman felt compelled to seek refuge overseas.

But, as is now well known, Cyril Ramaphosa defeated Dlamini-Zuma at the December 2017 ANC elective conference. Her camp had evidently failed to convince enough members of the ruling party that she was the most capable candidate, as well the one who best represented the progressive cause of the advancement of women’s rights. Instead, she was seen as an unscrupulous politician ready to protect her children’s father and their family interests at the expense of the country. Another attempt at a dynastic takeover had failed.

Elsewhere on the continent, though, such attempts have been more successful, though more recently facing challenges. In June 2018, Equatorial Guinea’s vice president, Teodorín Nguema Obiang, shared a news story on Facebook about Gabriel Mbega Obiang’s recent visit to France. Gabriel, who is Teodorín half-brother and the country’s hydrocarbons’ minister, had travelled to Paris to negotiate new oil contracts with French oil company Total. Commenting on the story, Teodorín wrote: “The traitors start to come to light”. Teodorín himself was being accused of corruption in France, and saw his half-brother’s move as a betrayal.

The incident shows the hostility between President Teodoro Obiang’s two sons who vie to succeed the 76-year-old dictator. The volcanic Teodorín – the son of Obiang and first lady Constancia Mangue – was for a long time the favourite to take over when his father dies. But his scandalous international playboy life has attracted negative press. A headline in French newspaper L’Expréss in June last year summarised the tone of his Parisian stopovers: “Alcohol, whores and coke”. Moreover, he has faced legal cases against him in countries such as the United States and France, where he has been sentenced in absentia to a suspended sentence of three years in prison for embezzling tens of millions of euros from his country and laundering the proceeds. These have undermined his prospects in favour of Gabriel.

“Gabriel is bound to win,” Mocache Massoko, the director of Diario Rombe, an online media outlet reporting on Equatorial Guinea from exile, told Africa in Fact. Gabriel “is cynical like his father and much more intelligent,” he says. The son of the president and his second wife, the Saotomese Cristina Lima, he is now thought to be his father’s favourite. Aside from that, he is a much more calculated strategist than his half-brother. For instance, he even attended a rally denouncing Teodorín’s “persecution” at the hands of the French justice system. Moreover, he appears to enjoy the support of foreign investors and western countries and has managed to surround himself with capable people.

Teodorín is known for his compulsive spending of state money – including booking international music stars for his private parties and buying mansions and luxury cars in the world’s fanciest capitals. Teodorín has been known to slap ministers in public. With his mother, he likes to humiliate the country’s ruling party barons. “In power, he would be a kind of Idi Amin,” says Massoko. Even if he did somehow gain power, it is unlikely that he would spend much time at home. “He dislikes living in his country, and spends most of his time abroad, on his yachts and everything else,” says Massoko.

The conflict between the two half-brothers has been long in the making. In his 2004 book Reines d’Afrique (Queens of Africa) Vincent Hugeux described Teodorín’s mother as the force behind his ambitions. Diplomats cited by Hugeux saw Mangue as “the real boss” in Obiang’s court. “She is an African Jewish mother,” said one of the them. The first lady, who was described by these sources as “the archetypal manipulator”, will likely continue to support Teodorín, whatever the cost.

Meanwhile, according to a complaint received by Spanish authorities in 2017, a Spanish police commissioner – who is himself facing several accusations of blackmail – was paid five million euros to investigate Gabriel Obiang’s fortune. According to Diario Rombe, there are indications that Mangue’s entourage was the origin of the assignment, which aimed to discredit the hydrocarbons minister and so compensate, competitively speaking, for Teodorín’s international scandals. Obiang senior, meanwhile, is delaying the designation of a successor – likely to prevent open war within his family. That, some will feel, might be a forlorn hope, with control over the country’s oil revenues at stake.

Marcel Gascón Barberá is a freelance journalist. He lives in Johannesburg and writes for several Spanish and international publications. He has previously worked as a correspondent for EFE Spanish News Agency in Romania, South Africa and Venezuela.