What India’s post-independence experience can tell us about South Africa’s political future

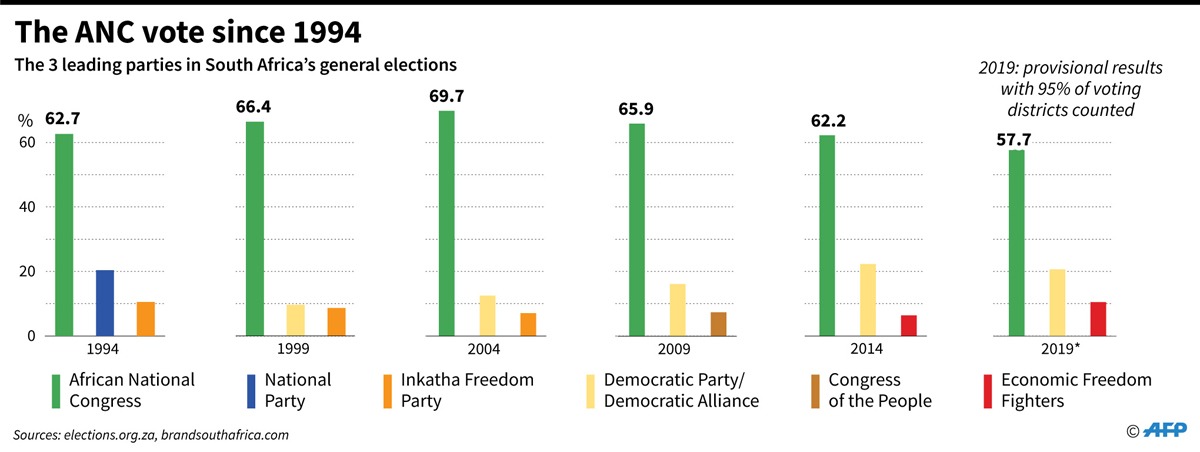

The ANC’s share of electoral votes has been in decline for the better part of the past decade. Based on its current service delivery record, mediocre at best, and its divided trajectory, the ANC will probably lose its national majority in 2024 and thereafter be dependent on others to form a governing coalition. This would mark a substantial change in the country’s political landscape and a potentially important shift in party-political support.

A woman holds up a souvenir medal on sale on the streets in Bloemfontein on 5 January, 2012 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) party. Photo: Alexander Joe/AFP

Is South Africa ready for this era of coalition government? Will such a scenario herald an era of democratic maturity and more inclusive politics or a descent into dysfunctionality? More importantly, what does it imply for governance?

To answer these questions, it is worth drawing parallels with India and the Congress party. What can the Indian experience tell us about South Africa’s political future?

The Indian National Congress (INC)dominated the electoral landscape without interruption since Indian independence from the British in 1947. It finally lost this majority in the elections of 1977 – after three decades in power – setting the stage for an era of (often messy) coalition politics. Similarly, after the end of apartheid and the advent of multi-party democracy in South Africa, the ANC has won every national election with a clear majority since 1994. Now, as it approaches the end of its third decade in power, the jury is out on whether the ANC will continue to retain its status as the dominant ruling party or suffer the same fate as the INC, which initially moved into the role of opposition, but now finds itself in the political wilderness and searching for relevance.

There are a number of similarities between the two parties. First, both were liberation movements, which then turned into governing parties. While the INC pursued the goal of independence for India, the ANC led the charge to bring an end to apartheid in South Africa. These endeavours bestowed upon each of them a moral legitimacy to govern, as was evidenced by the strong majorities they enjoyed in the first two decades of rule. Furthermore, the ANC was consciously modelled after Congress, and many of its leading lights like Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo and Walter Sisulu drew inspiration from Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Second, the two organisations are ideologically congruent. Both are “broad churches” or big tents with social democratic leanings, who operate under “the idiom of consensus-seeking internal politics”, as noted by Thiven Reddy of the University of Cape Town in a 2005 university research paper. Thirdly, both parties have presided over societies which were deeply unequal and divided, with vast ethnic differences, and presented themselves as inclusive and unifying movements.

Eventually, however, in the life of every liberation movement, there is an inflection point where past performance and history counts less than future service delivery. In this context, it is worth reflecting on the experiences of the Congress party, which did not heed the initial warning signs from its electorate. The general elections held in 1967 under the leadership of Indira Gandhi saw Congress plagued by internal dissent and factionalism, resulting in a loss of 100 parliamentary seats and four percentage points of the popular vote. Tellingly, it lost eight state elections thereafter, which seriously threatened its dominance, but it continued to remain “the major political force in the country”. However, a mere 10 years after this, India rejected the Indira Gandhi-led Congress party en masse.

That result shifted the power balance that gave rise to the first non-Congress (the Janata Party) and first coalition government, which subsequently became institutionalised, and part and parcel of Delhi’s political culture.

Much like Congress, the ANC has been criticised for fostering nepotism, infighting, complacency, and factionalism. An ongoing economic downturn, high unemployment and the party’s failure to fulfil electoral promises, has seen it lose both goodwill and electoral support, while a series of grotesque corruption scandals has eroded its moral legitimacy. Indeed, many of the trends evidenced in India are now mirrored in South Africa as the liberation dividend fades. In the 2019 national election, the party achieved 57.5% of the vote, its worst showing ever, indicating an almost 10% decline at the polls since 2009.

Much like Congress, the ANC has been criticised for fostering nepotism, infighting, complacency, and factionalism. An ongoing economic downturn, high unemployment and the party’s failure to fulfil electoral promises, has seen it lose both goodwill and electoral support, while a series of grotesque corruption scandals has eroded its moral legitimacy. Indeed, many of the trends evidenced in India are now mirrored in South Africa as the liberation dividend fades. In the 2019 national election, the party achieved 57.5% of the vote, its worst showing ever, indicating an almost 10% decline at the polls since 2009.

Sreeram Chaulia, professor and dean at the Jindal School of International Affairs, saliently observed in a 2014 analysis that the “ANC’s trajectory is heading the way of the Congress, ie., a gradual erosion in its popularity as the fond memory of older generations for the party that gained freedom from colonialism is replaced by frustrations of younger generations for its unfulfilled promises and governance flaws.”

South Africa’s electorate has changed significantly since 1994. Young voters who did not personally live through apartheid feel less affinity and loyalty to the ANC than their parents. On the contrary, young people and university students have actually been at the forefront of many anti-government demonstrations in recent years, most notably the #FeesMustFall protests in 2015.

Voters rush to cast their votes hours before polling stations close at the Durban City Hall in South Africa’s sixth national general elections on 8 May, 2019. Photo: Rajesh Jantilal/AFP

Alongside the growing trend towards greater urbanisation, and declining voter turnout in rural areas, evidence suggests that the ANC’s share of voters will continue to edge south of 50% unless something drastically changes. The warning signs are already there – as evidenced by the ANC’s electoral defeat in three major municipalities (known as metros) during the 2016 local government elections.

These elections were significant for many reasons, not least because it was a stark wake-up call for the ANC to shape up or ship out. It also witnessed for the first time a shift away from historical race-based to issue-based voting patterns and a sense of apathy among the ANC’s traditional constituents. The surprise result demonstrated not only the functionality and vibrancy of South Africa’s democracy, but also early signs of a political culture shifting away from loyalty towards one of political accountability. This has now sparked enthusiasm among minority parties, who have seen that a viable alternative to the ANC can be achieved. However, an important distinction is necessary- opposition parties will need to view themselves as part of the solution rather than as the full solution. Pragmatism, rather than ideology, will need to be the overriding consideration if they are to capitalise on anti-incumbent sentiment.

In his comparative assessment, Chaulia notes: “As was the case in India in 1977, a right/left combination of likeminded allies will be required in the long run to displace [the] ANC from power. Ultimately, as the party of Gandhi and Nehru abandoned idealism, India found political alternatives. Likewise, South Africa’s parallel voyage away from single party rule is underway.”

Although the ANC recovered some of its losses during the national election in 2019, largely on account of the personal popularity of Cyril Ramaphosa, South Africa’s dire economic situation, rampant corruption and ongoing governance failures since then suggest that this decline will continue. Without an outright ANC majority, the role and importance of kingmakers and opposition parties will become more significant.

Richard Calland of The Paternoster group, a South African political risk consultancy firm, believes that “ANC weakness may not be a good thing, in terms of both consistent policymaking and building national unity. We have now seen the effect of factionalism and division within the ruling party, and the overall impact has been to destabilise government, undermine corruption-combating efforts and diminish the social contract that was painstakingly built during the first decade of democracy, post-1994.”

In an ideal world where political parties represent certain interests, a coalition of different parties could be more inclusive, more representative and more responsive to the needs of its electorate. There are compelling reasons why coalition formations may be better suited to developing countries with diverse populations and interests – not least because they advocate consensus and pro-poor policies.

Research by Professors Torben Iversen of Harvard and David Soskice of the London School of Economics published in 2006 reveals that the rise in inequality is slower in countries that have coalition governments. On the other hand, countries with a majority government have witnessed a rapid rise in inequality. The researchers found that coalition governments are more focused on the re–distribution of resources, which is not a priority for majoritarian governments.

Mihir Sharma, in a Bloomberg opinion piece in April 2019, further outlines the case for coalition governments, citing the Indian example: “For three decades, until elections in 2014, India’s voters refused to give any single political party a majority in Parliament. It was an age of coalitions — of dissonant and divided cabinets, prime ministers who ruled by consensus, and policy constructed after painstaking negotiation. It was also the era when the Indian economy came of age. The country opened up, reformed, achieved high growth rates and lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty.”

However, the problem, as noted by political scientist Professor Nic Cheeseman, is that coalitions have a dark side too. While they may enable new parties to get a foothold in government, they can also be inherently unstable, and delivery can be bogged down in bureaucratic inertia and policy paralysis. This was on clear display in South Africa when the Democratic Alliance (DA) and Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) radical ideological differences caused a breakdown in their working relationship.

Despite their obvious differences, the DA and EFF’s unseating of the ANC in 2016’s local government elections was fuelled by pragmatism. EFF leader Julius Malema is on record as saying that the arrangement was a marriage of convenience, while the DA adopted the mantra that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. However, here it is important to make the distinction between “ideological coalitions” and “governance coalitions”. In this case, the parties attempted to achieve the latter, but with little success in the absence of a formal power sharing arrangement.

Lukhona Mnguni, an academic at the University. of KwaZulu-Natal and radio host at Power 98.7, believes “the problem in South Africa is that political parties have not identified themselves along ideological lines. Given the cosmopolitan nature of the country’s electorate, most political parties seek to appeal to all sections of society. A more significant problem in South Africa is that there is no legislation that adequately gives directives on how coalition formation should be undertaken during pre- and post-election periods respectively. There is a need for legislative development in this respect.”

Since the 2016 arrangement, the DA has pivoted to the right of the political spectrum, diluting its mass appeal. As a result, it is difficult to envisage this type of configuration replicated again. The DA working alongside the ANC also seems an unlikely prospect, given the intense competition for power between the two. Instead, it seems that the ANC and the EFF are ideological aligned bedfellows that would suggest a shift to the left in policy direction and the pursuit of a more nationalistic agenda.

The kingmaker role in South African politics, a position the EFF currently occupies with great effectiveness, will likely become even more relevant. Moreover, intense competition for this space will emerge, with parties like former Johannesburg mayor Herman Mashaba’s Action SA competing, albeit at a regional level. Amid this power vacuum and shifting environment, there is significant scope for new parties to fill the gaps across the ideological spectrum. Appealing to younger voters, many of whom are either apathetic and/or uninspired by the current range of options, could also materially alter the voting dynamic. All of this fluidity introduces further complexity and uncertainty to the political landscape.

On balance, coalitions are somewhat of a mixed blessing. In theory, they can deliver a more inclusive approach to governance but also create an opportunistic style of politics based on the exchange of favours, which can actually undermine, rather than strengthen, accountability. In India, the formation of coalition governments reflected the transition in politics away from the national parties towards smaller, more narrowly based regional parties. On a positive note, it has helped keep fundamentalism at bay and stimulate diversity of views, but it has also created a culture of short termism and political instability.

Looking at South Africa, an optimistic view suggests that enhanced political competition will improve governance by reducing complacency. The flipside is that it could exacerbate current dysfunction. Regardless of which way it goes, a shakeup of the status quo is badly needed for a restless population beleaguered by unmet expectations and unkept promises.

RONAK GOPALDAS is a director at Signal Risk, an exclusively African risk advisory firm. He was previously the head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) for a number of years, where he managed a team who provided the firm with in-depth analysis of economic, political, security and operational dynamics across sub-Saharan Africa. He holds a BCom degree in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) and a BCom (Hons) from the University of Cape Town (UCT). He also has an MSc in finance (economic policy) through the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.[