Whereas the concept of “good governance” has a long history in politics, government policies, and anti-corruption activism, “inclusive governance” is a more recent adoption in political and international development.

Inclusive governance seemingly originated from the United Nations’ pledge that “No one will be left behind”, formulated in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2015). Similarly, “good governance” appears as one of the “seven aspirations” of the African Union Agenda 2063.

In the author’s view, the practical definition of good governance should be expanded to include “the process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented,” as set out by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) in 2008.

Maasai people gather under a baobab tree at Ol Tukai, 100km west of Arusha in Tanzania, during a political rally in October 2010. (Photo: Tony Karumba / AFP)

In this context, inclusive governance is defined as the process of decision-making that engages formal stakeholders to include people and groups that have been generally left behind, excluded, disempowered, or marginalised.

Formal stakeholders include elected representatives, government officials, civil society organisations, the judiciary, the private sector, regional economic communities, business lobbies, multinational corporations, multilateral organisations, UN organisations, and donor agencies.

According to the United Nations Development Programme, marginalised people and groups are determined based on the following five key factors:

- Discrimination: gender as well as ethnicity, age, class, disability, sexual orientation, religion, nationality, indigenous, migratory status etc.

- Geography: isolation, vulnerability, missing or inferior public services, transportation, internet, or other infrastructure gaps due to their place of residence.

- Governance: ineffective, unjust, unaccountable, or unresponsive global, national and/or sub-national institutions; inequitable, inadequate, or unjust laws, policies, processes, or budgets.

- Socioeconomic status: deprivation or disadvantages in terms of income, life expectancy and educational attainment; fewer chances to stay healthy, be nourished and educated; fewer chances to acquire wealth and/or benefit from quality healthcare, clean water, sanitation, energy, social protection, and financial services; and

- Shocks and fragility: people who are more exposed and/or vulnerable to setbacks due to the impacts of climate change, natural hazards, violence, conflict, displacement, health emergencies, economic downturns, price, or other shocks.

It takes leadership to “make decisions” and “implement decisions”, given that in any institution or group of people, you may find leaders and/or managers. Leaders and/or managers act within structured organisations to achieve results (products, services) for the development of these organisations and the betterment of social groups – also known as customers, clients, citizens, or communities. Leaders are the actors who can perform towards the objectives, expectations, and ambitions of institutions and other social organisations.

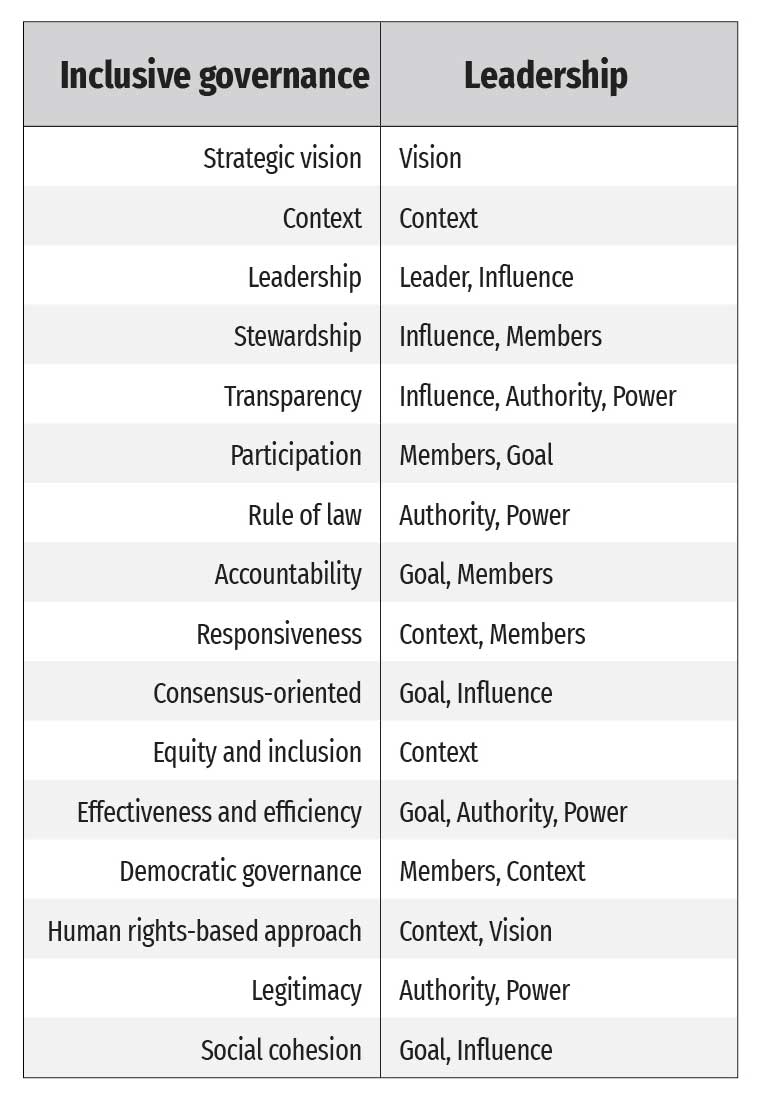

The UNDP has introduced the following eight basic key elements of good governance: transparency, participation, rule of law, accountability, responsiveness, consensus-oriented, equity and inclusion, effectiveness, and efficiency. These basic features are expanded by strategic vision, meaning that leaders and the public engage in a long-term perspective on human and institutional development; that perspective is grounded in a specific context. Other features like stewardship and leadership are therefore added to the basic ones identified above. According to the OECD (2020), inclusive governance comprises the following related concepts: good governance, democratic governance, a human rights-based approach to development, legitimacy, and social cohesion.

Based on the description above, Table 1 tentatively shows how inclusive governance and leadership intersect in most of their respective components.

Table 1: Intersecting components between inclusive governance and leadership

To understand the intersection between the two, consider these two examples. First, an institution or a group of people that are engaged in the process of inclusive governance would implement its vision with a leader or leaders who use their authority to gather members and other stakeholders in their context to achieve the common goal. Practical examples are the governments of Cameroon, Chad, and Guinea, which have behaved as inclusive organisations in organising “inclusive dialogues” in recent years.

Second, leaders in the process of inclusive governance have the legitimacy to make and implement decisions to attain a strategic vision with transparency, participation, accountability, rule of law, and responsiveness, in respect of equity and inclusion, democratic governance and social cohesion. Practically, some African leaders show inclusive leadership characteristics in development or political initiatives (African Development Bank, regional development agendas, capacity building programmes, etc).

What does effective leadership towards inclusive governance look like? Leadership is exercised with a leader and team members. People who form a set and cooperate to achieve a common goal or purpose, constitute a team. As Seung-hee Lee and co-authors set out in a 2006 article in the International Journal on E-Learning, teams are formed to achieve specific interdependent learning goals or task performances. Team members work under the authority, power, and influence of the team leader.

The effectiveness of leadership, according to Gary Yukl (2006), relies upon the group influence process, i.e., the extent to which team members trust each other and cooperate in accomplishing task objectives.

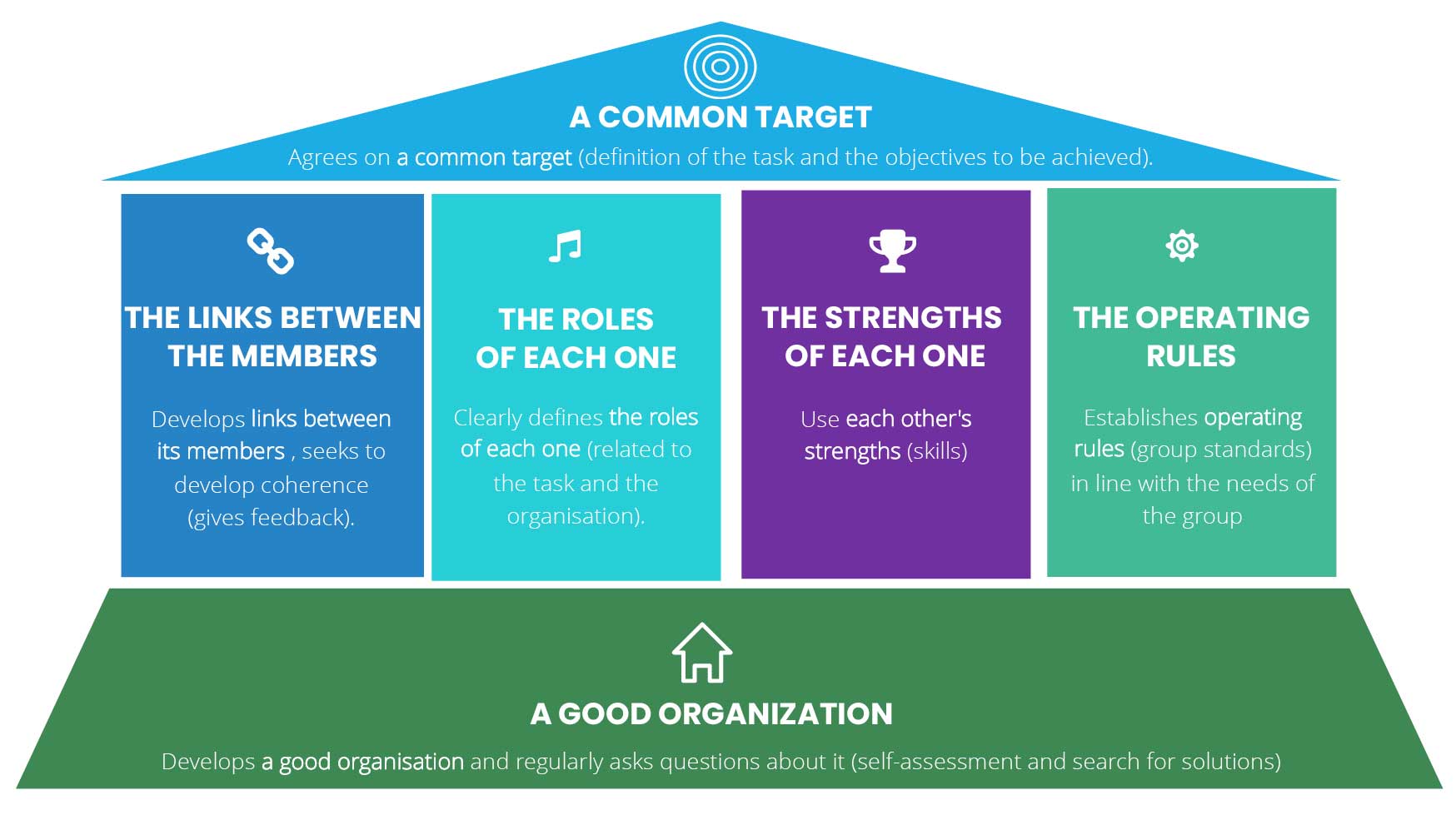

In a recent 2020 study, the author Andre Mboulé identified the following characteristics of an effective team (Figure 1).

A good organisation, as the foundation of the team;

- The four pillars: the links between the members, the roles of each one, the strengths of each one, and the operating rules;

- A common target as the “roof” of the team “house”.

Figure 1: Characteristics of an effective team (Mboulé, 2020)

The understanding of how leadership intersects with inclusive governance demonstrates that the characteristics of an effective team, as shown above, contribute to the effectiveness of inclusive governance. In effect, any institution that engages in inclusive governance would be structured in effective teams with leaders that seek performance (effectiveness, efficiency) in the achievement of common target(s).

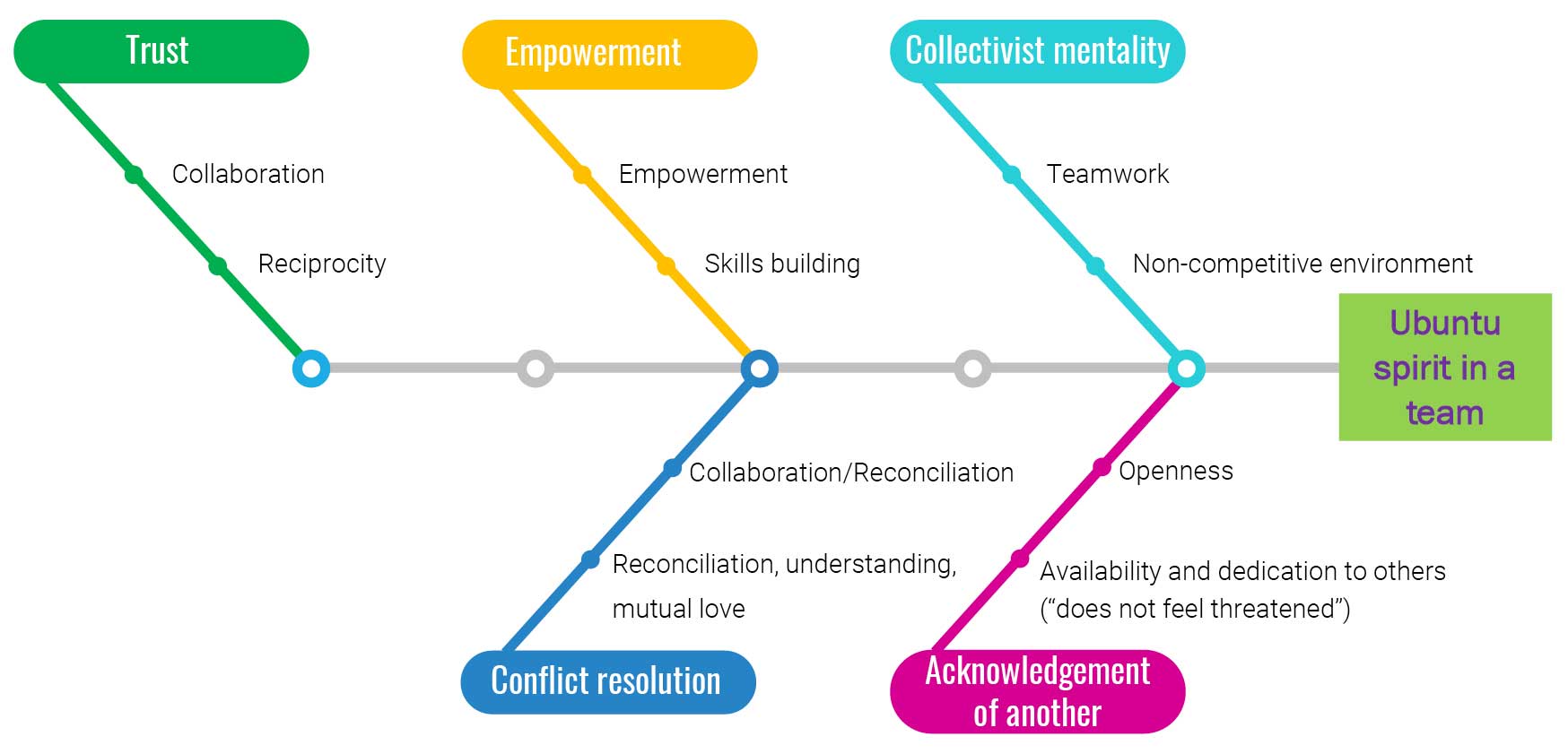

In the African context, elites and other stakeholders earnestly seek a paradigm shift based on a typically African philosophical worldview. To this extent, African and non-African scholars have studied Ubuntu as a symbol of “an African common worldview” or an “Afrocentric management paradigm” (Authors Luchien Karsten and Honorine Illa, in their 2001 article, ‘Ubuntu as a management concept’, in Quest, for example, or Prince Guma’s 2012 Social Science Research Network article, ‘Rethinking Management in Africa: Beyond Ubuntu’) in contrast to western management paradigms.

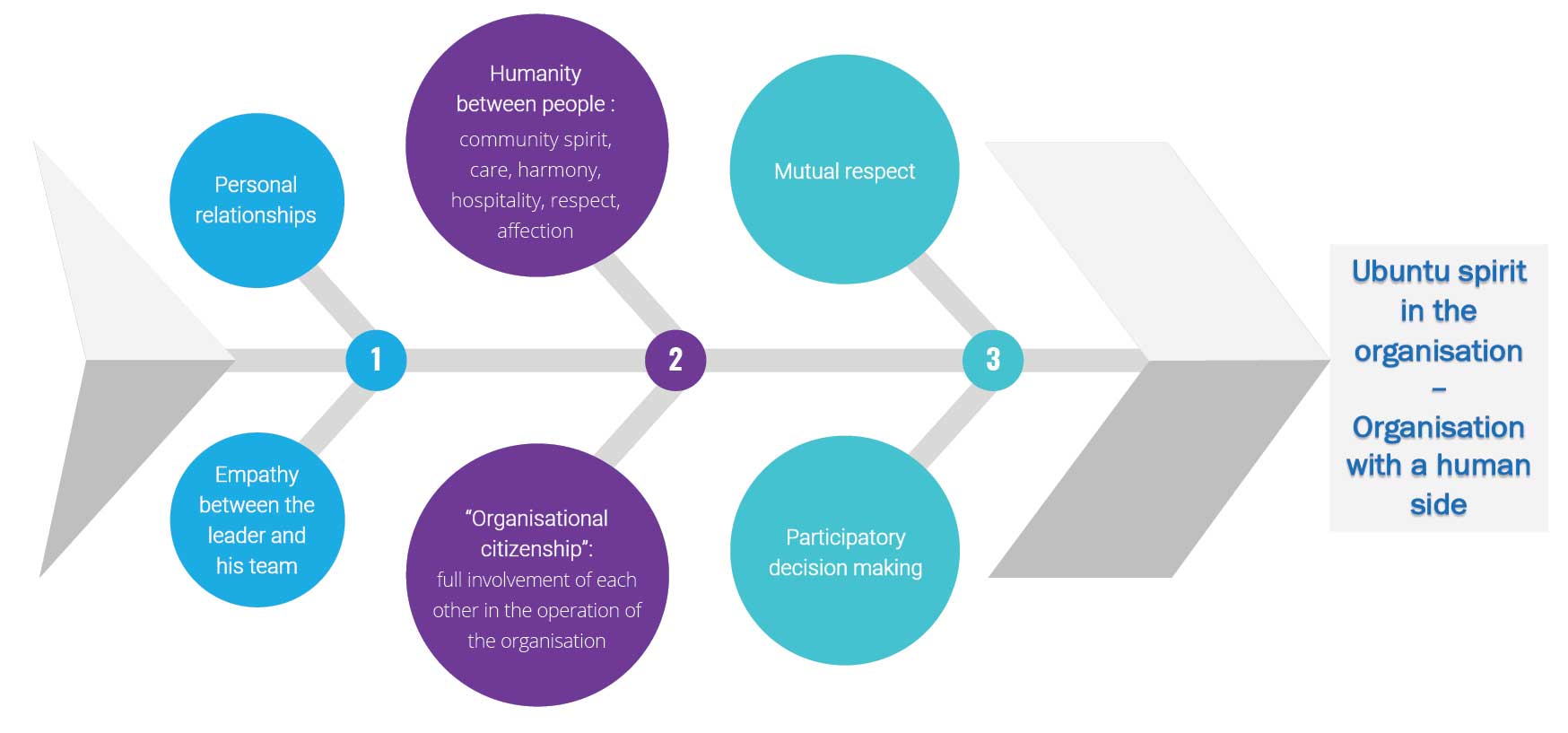

Ubuntu, the African philosophy, finds its meaningfulness in this expression in Xhosa or Nguni languages: “Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu”, which means “a person is a person through other persons” which indicates that ubuntu involves teamwork, attention to personal relationships, mutual respect and empathy between the leader and his team members, and participative decision-making. In an organisation “with a human side”, with ubuntu, individuals and groups demonstrate “humaneness” for each other. According to Karsten and Illa, ubuntu will show a way to work together and create a diverse (“rainbow”) mentality in our organisations; a mentality characterised by a high degree of cultural, racial, religious, tribal, and political tolerance. A “rainbow” mentality would inevitably foster inclusion.

In studying how the ubuntu concept could help define an African endogenous leadership style, the author has identified the following determinants: trust, empowerment, a collectivist mentality, conflict resolution, and acknowledgement of another (Figure 2). These determinants would likely form an “ubuntu spirit” in a working team.

Figure 2: Determinants of the ubuntu leadership style in a team (Mboulé, 2020).

Within an organisation, the ubuntu leadership style would enable the following determinants: personal relationships, humanity between people, mutual respect, empathy between the leader and his team, “organisational citizenship”, and participatory decision-making (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Determinants of the ubuntu leadership style in an organisation (Mboulé, 2020).

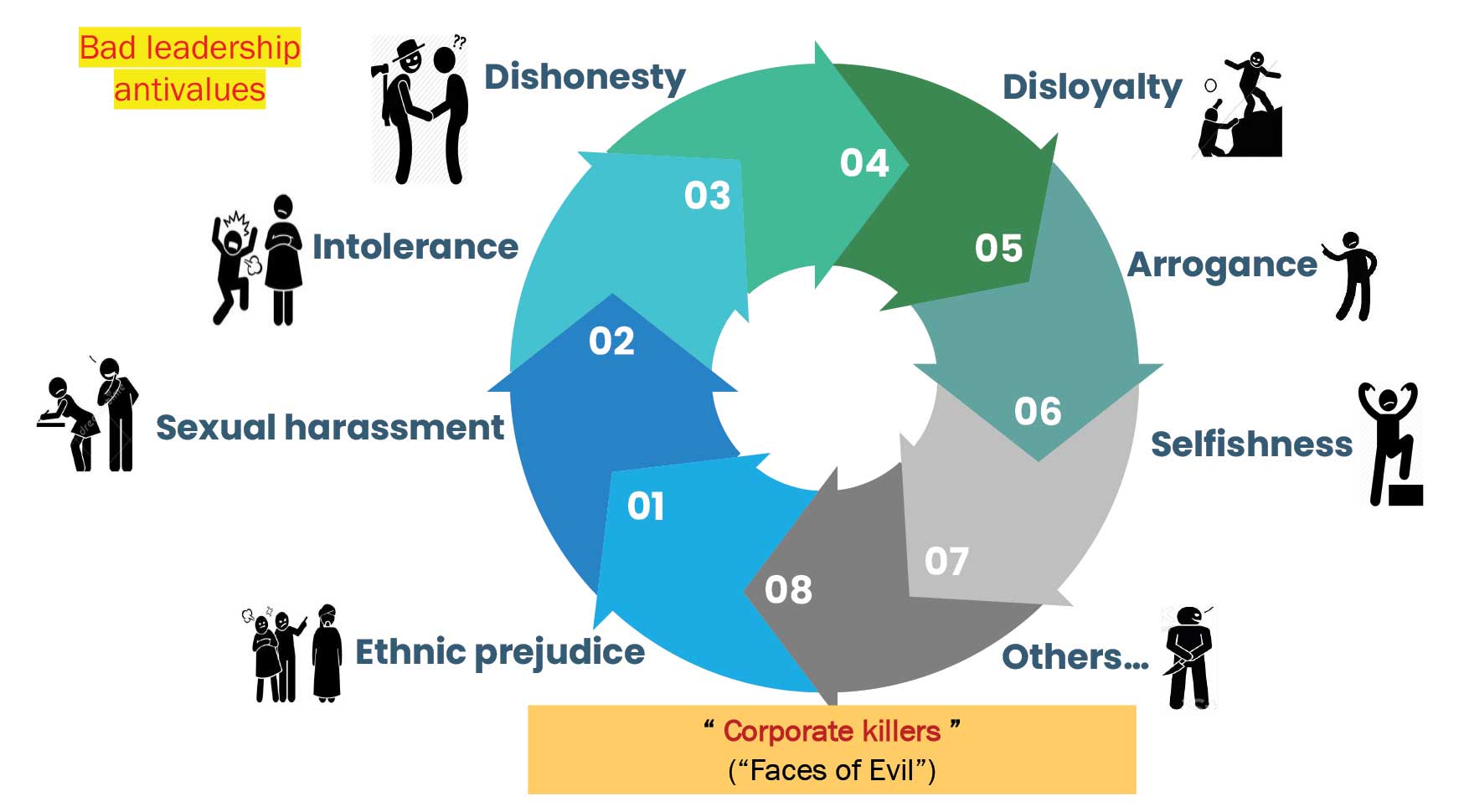

However, among the dynamics that could undermine good or effective leadership, researchers have uncovered the manifestations of wickedness and evil in organisations and the workplace: they have been identified as “faces of evil” or “corporate killers” (Dahlgaard, SMP, Dahlgaard, JJ, & Edgeman, RL (1998). These anti-values constitute the germs of bad leadership, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Bad leadership anti-values.

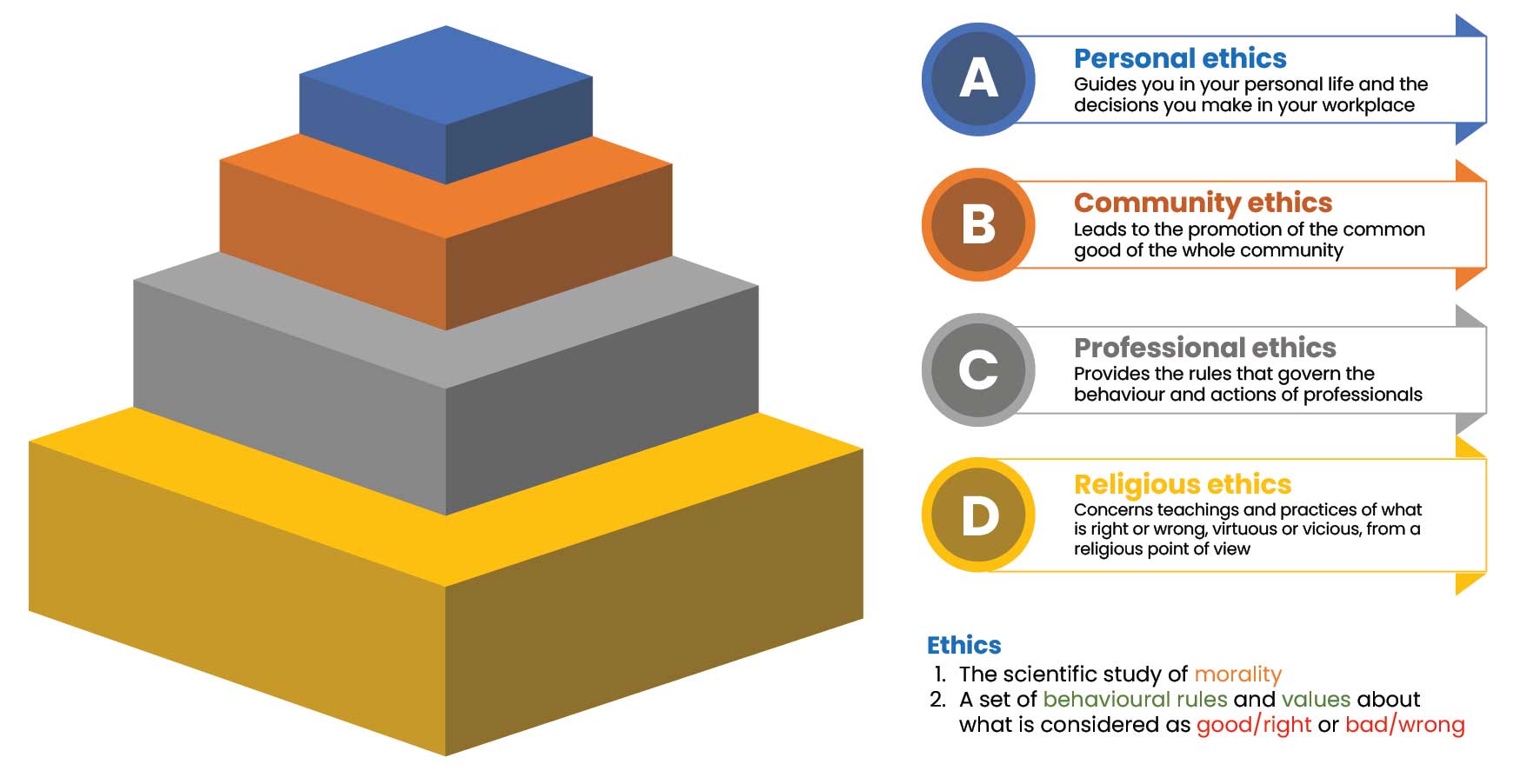

In conclusion, effective or good leadership must be founded on solid, culturally rooted, and universal values, so that it may not be perverted by behavioural rules and values encountered in different ethical settings. The following categories of ethics (Figure 5) provide guides, rules, values, teachings, and practices that could distort or contradict the determinants of effective or good leadership.

Figure 5: Categories of ethics (Mboulé, 2022).

Dr Mboule Andre, PhD, an engineer manager and international consultant, is the promoter for KEMT Leaders & Consultants, Cameroon & South Africa. He has over 39 years of managerial/leadership training experience, working in more than 30 countries in Africa and Europe, primarily in state-run health facilities and education facilities, consulting firms, and international organisations such as WHO, AfDB, EU, AFD, GIZ, WB and Lux-Dev.

Since 1989, Dr Mboule has been an associate lecturer and researcher, mentoring students' theses within academic institutions such as the Catholic University of Central Africa (UCAC)-Ecole des Sciences de la Sante (ESS-Yaounde) and the University of Douala - Institute of Fisheries Sciences (ISH-Yabassi). He also trains senior executives in lifelong education programmes. He primarily teaches project management, performance management, leadership development, entrepreneurship, health informatics, and health technology management.