Lessons from the schoolboy who harnessed the wind

In his bestselling memoir, The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Creating Currents of Electricity and Hope (2009), William Kamkwamba laid bare the challenges faced by millions of Malawians living in rural areas without access to electricity.

Kamkwamba’s epic memoir, in which he recounts how, forced to drop out of school at 14 because famine had ruined his family’s harvest leaving them unable to pay his fees, he used books from the local library to teach himself how to build a windmill using scrap materials to generate electricity.

His innovation and determination to provide his village, Kasungu, with electricity and water garnered first national and then international attention. Today the teenager, whose story culminated in a book and a film (available on Netflix) is still changing lives through his Moving Windmills project. The Environmental Studies graduate and entrepreneur, and his Moving Windmills project, have a long-term plan to distribute power using low-cost technologies, which will be anchored by solar, wind and rivers (mini-hydros).

William Kamkwamba attends the premiere of the film of his book, The Boy Who Harnessed The Wind, during the 2019 Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. Photo Rich Fury/Getty Images/AFP

The challenge is huge. Some 83% of Malawi’s population of approximately 19 million people lives in the rural areas. Online energy portal Energypedia noted in a 2020 report that: “Malawi’s National Energy Policy estimates that 93% of total energy demand is met by biomass. Households consume 84% of the total primary energy. A staggering 99% of household energy is supplied by biomass…. Less than 2.3% of the total national energy demand is met by electricity, 3.5% by liquid fuels and gas, and 1% by coal.”

Energypedia’s report said that only 18% of the population has access to the grid, while the almost blanket use of charcoal and firewood for domestic use is “exerting significant pressure” on the country’s forest resources.

A 2017 study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), found that Africa has huge untapped resources for renewable energy, which must be used to meet increased demand.

Meanwhile, the Malawi Renewable Energy Strategy estimates that the country could actually connect 27% of the population by establishing decentralised mini-grids in communities of 250 people located at least 5 km from the national grid. However, since the Malawi Rural Electrification Project (MAREP) rolled out 40 years ago, 96% of the country’s rural population still remains off grid. At the present rate, Malawi needs at least 960 years to connect every rural home or institution and achieve energy for all.

“I’m very interested in finding ways to use the knowledge that I have gained through my education and interacting with people to solve some of the problems people are facing in Malawi,” Kamkwamba told Africa in Fact.

Malawi’s Department of Energy Affairs agrees that the country cannot eliminate the huge unmet need for electricity by extending the national grid alone. The country’s revised National Energy Policy recognises the challenges of continually extending the grid because some rural populations live in hard-to-reach places. Instead, the policy recommends that Malawi diversify the generation and distribution of electricity by embracing the use of solar, water and wind mini-grids to accelerate rural electrification.

“Rural access is to us still on the lower side; we wish we could have done more [by now]. The 2018 census shows that 84% of people in Malawi live in rural areas. This means we are still doing them a disservice,” Edgar Bayani, the Director of Community Energy Malawi (CEM), says. Bayani suggests that Malawi’s energy woes would be met if the government operationalised key policy documents such as the National Energy Policy, Renewable Energy Strategy and Action Agenda.

Kamkwamba, meanwhile, is actively pursuing his ambition to assist Malawi by coaxing a cadre of youngsters to embrace innovation from a very young age. This includes the creation of an innovation centre in Kusungu, which will be a hub for “students, mentors and community to create innovative solutions to Africa problems”.

“We talk about wind and solar because it’s a simpler and cheaper way to give us electricity and irrigation,” Kamkwamba says. “Clean water and power are our right as humans on this earth, and for too long our governments in Africa have failed to provide these things.”

The Moving Windmills Project foundation is working with five primary and secondary schools in Kasungu to solarise their power and has installed internet-in-a-box systems, with the primary goal of bringing consistency to every school day for hundreds of students.

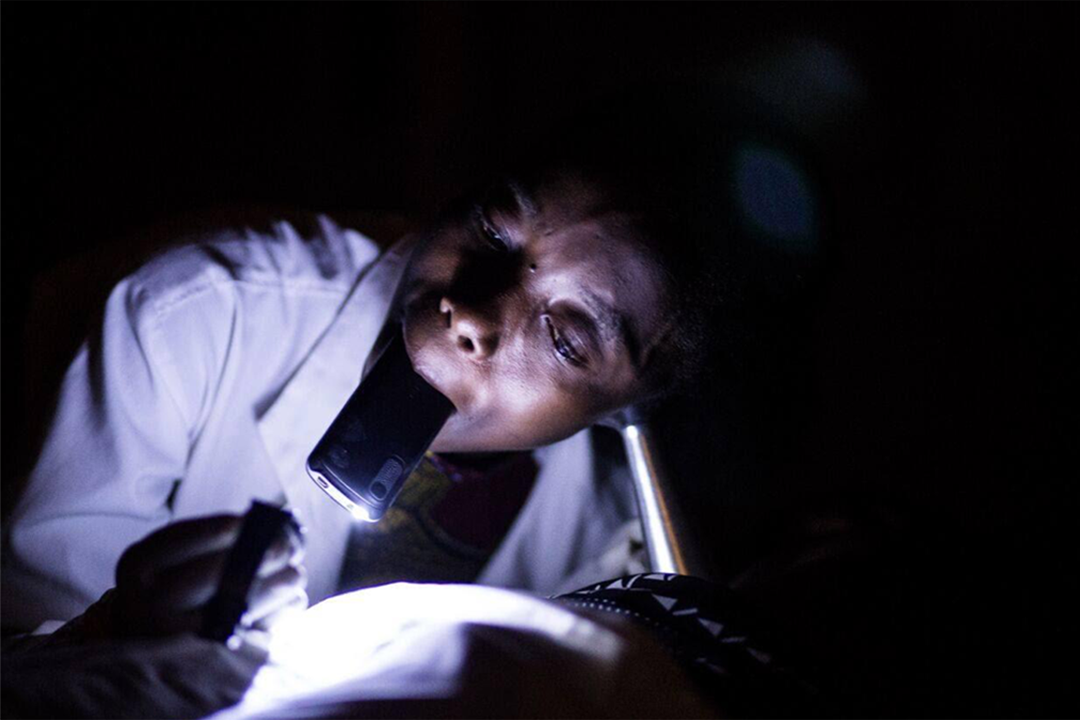

“We have been able to build three classroom blocks with two classes each for the local primary school, Wimbe Primary School,” Kamkwamba says. “These new classrooms have solar panel installations that allow the students to study late into the night. We have also installed solar panels and systems in Kachokolo High School, which has allowed the students to use computers for their studies for the first time in their lives.”

Malawi needs to invest $3 billion to leverage abundant renewable energy resources to save money, while providing reliable electricity for growth and rural electrification, according to a 2019 study by the Rocky Mountain Institute. “Malawi has an abundance of resources with which a sustainable energy sector could thrive. Ending energy poverty and ensuring that no country or person is left behind must become a priority for all stakeholders,” the study said.

David Keith, an African energy sector expert at Tetra Tech International Development Services, agrees that billions of dollars in investment in Africa’s electricity sector is needed. “The key here is we really believe the energy sector is just another industry—it is not a government enterprise. And if we could get that sort of belief across, then governments will get out of the power business,” said Keith, who has worked on energy projects in South Africa, Malawi, Uganda, Ghana, Benin, Tanzania, and for the West Africa Power Pool.

To augment Kamkwamba’s efforts in powering and lighting Malawi, the country’s government is now working with Independent Power Producers (IPPs) to help the country in power generation endeavours. It has engaged 14 IPP companies to generate solar power and others to use wind, geothermal, waste and coal.

Helping to fill the energy void in his home village and lessening energy poverty, Kamkwamba’s Moving Windmills Project foundation has established a biogas digester project in Kasungu that uses cow dung to generate gas, which is used for cooking and lighting homes. It has also taught villagers how to fix water wells to avoid cultivating diseases that come from lack of maintenance.

“Deforestation is a huge problem in Malawi, which only adds to the problem,” he said. “People cut down trees because they have no power to run electric stoves, etc. So, they use firewood. This is a problem all over Africa. The windmills don’t produce enough power to operate a stove, but with some more innovation, this could be easily solved.”

Kamkwamba still regularly speaks at conferences and other events, where he continues to explore various renewable energy sources that could have the potential to help Malawi.

“Africa is blessed with renewable energy and does not need fossil fuels to help people access energy and create growth, and the cost of renewables has come down significantly and is much lower than that of fossil fuels,” Mohamed Adow, the founding director of the Nairobi-based think tank Power Shift Africa told Africa in Fact.

Collins Mtika is a Malawian independent Investigative Journalist and founder of the Centre for Investigative Journalism in Malawi (CIJM). He works for the Times Media Group which publishes The Daily Times, the Sunday Times and Malawi News, for which he is currently bureau chief for the Northern region.