Last month, Glencore, a multinational mining and commodity company, pleaded guilty to long-standing charges of systematic bribery, corruption, and market manipulation to authorities of the United States (US), Brazil, and the United Kingdom (UK). Glencore was subsequently fined $1.2 billion for these offences. While this is the right step towards attaining some level of accountability in the abovementioned countries, it begs the question: Where does it leave African mining jurisdictions that are challenged with the same systematic bribery and corruption practiced by Glencore?

The logo of Glencore at the Swiss commodity trading giant’s headquarters in Baar, central Switzerland. Photo by Fabrice Coffrini/AFP

The earliest reports on Glencore covered a bribery scandal in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), involving the controversial businessman Dan Gertler, who bribed Congolese officials on behalf of Glencore to secure mining contracts with the government in 2008. In their West African operations, particularly Nigeria, Cameroon, Ivory Coast and Equatorial Guinea, Glencore is reported to have paid approximately $79.6 million to intermediary companies in order to secure improper advantages to obtain and retain contracts with state-owned entities between 2007 and 2018, as indicated by the US Department of Justice (DoJ).

The bribes were concealed by entering into questionable consulting agreements, paying inflated invoices, and using intermediary companies to make corrupt payments to foreign officials. For instance, in Nigeria, Glencore and its subsidiaries paid over $52 million to intermediaries with the intention that the funds be used to bribe Nigerian officials. The US public statement highlights that much of the bribery and corruption took place in Africa. However, little to no intervention has been initiated by the several African governments implicated to investigate these matters in their respective countries. Limitations inhibiting African governments from doing so vary from country to country.

The African Energy Chamber (AEC) has called for African governments to investigate Glencore’s dealings in their operations and examine the cases at a local level. It has also excluded Glencore from the upcoming African Energy Week in October 2022. However, it remains unclear what the consequences for Glencore’s executive team will be, and what African governments will do to prevent this in the future. The US DoJ confirmed that Glencore’s executive team took part in or approved the schemes. To conceal these schemes, Glencore traders would use codewords such as chocolates for bribe payments with no attempt to hide the corrupt practices. Where sufficient evidence is given, criminal prosecution should follow – that is how executive teams involved should be held accountable.

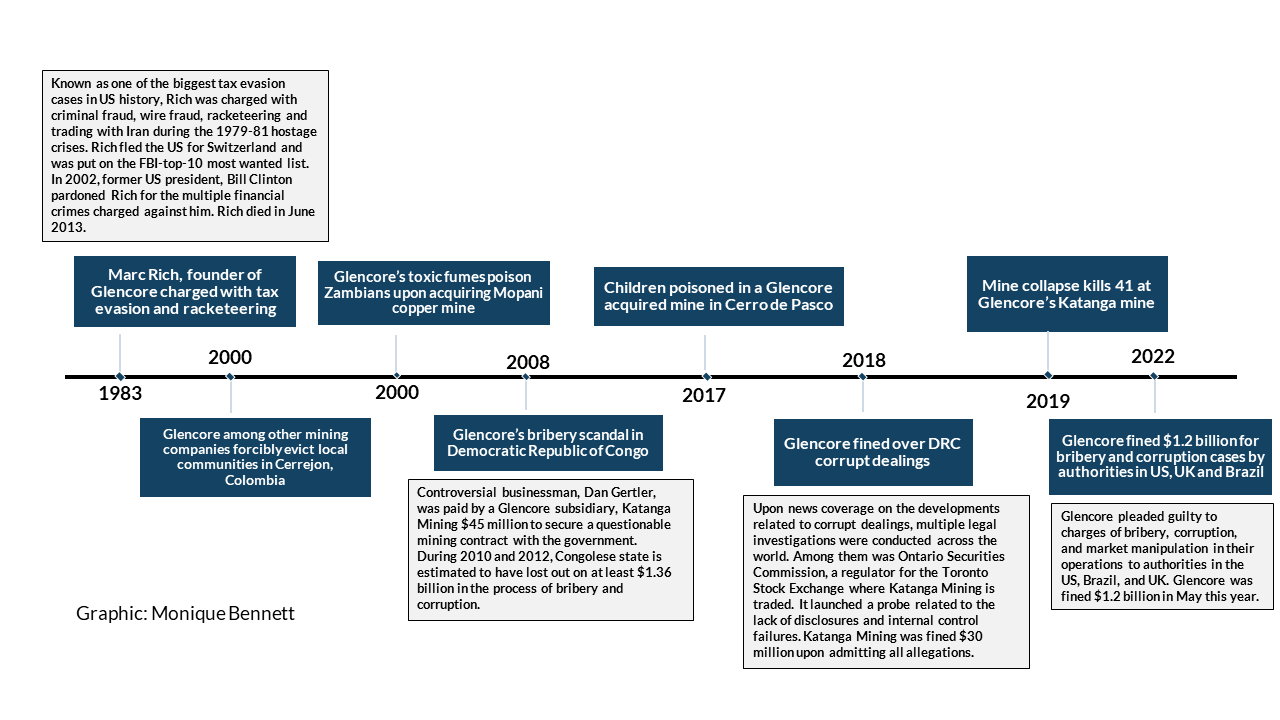

The timeline below illustrates the significance of misconduct by Glencore over the past two decades in some of the mining jurisdictions in which they have operated.

The extractives industry is – at least in principle – governed by global and local codes and standards, such as the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). These are established primarily to improve and promote transparency in the extractives industries and to overcome the challenge of revenues being diverted for unproductive purposes and not being properly accounted for. In 2011, Glencore listed as one of the EITI supporting companies. Part of this support includes companies advancing transparency and good governance in the industry, promoting the expectations for EITI supporting companies and by contributing financially to the international management of the EITI process.

The expectations delineated for EITI supporting companies include making comprehensive disclosures in accordance with the EITI Standard in all EITI implementing countries where the company and its controlled subsidiaries operate. Another expectation is that supporting companies would publicly disclose taxes and payments to governments at a project-level in line with the EITI Standard. Where “disclosure is not feasible”, the requirement is to have country-specific legal or practical barriers to disclosure publicly explained. EITI implementing countries that have been implicated in the Glencore bribery case include the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, and Cameroon. This raises questions as to how credibly EITI supporting companies and implementing countries are assessed if such levels of bribery and corruption practices pervaded for over two decades in the respective countries. Furthermore, the EITI reporting process could be strengthened in order to equip the EITI Secretariat to assess the dealings of supporting companies in implementing countries.

Glencore’s corrupt practices, along with the countries willing to be corrupted by bribery, have been inconsistent with the EITI Principles and thereby undermined the EITI Standard. Though the EITI Board has released a statement condemning Glencore’s misconduct, it has not outlined real consequences for the company as a supporting member. This points to two of the key challenges of the EITI process. One is its inability to prevent corruption effectively. The second is its insufficient capacity to work with implementing countries to investigate reported revenue discrepancies highlighted in country-level reports. However, the statement calls for Glencore to actively participate in the EITI Commodity Trading Group to ensure that lessons can be learned and measures identified that can prevent such practices from happening again.

The EITI board has called for governments of the implementing countries to examine the cases, act, and provide adequate preventative measures. The EITI should support the investigation process and equip implementing countries such as Nigeria and DRC with resources and tools that will lead to justice. Finally, the US DoJ indicated that Glencore will be scrutinised by an independent monitor over the next 3 years as part of the overall deal. This is a critical step that needs to be tracked and adhered to rigorously. Further to this, the assigned independent monitor will need to be transparent regarding the findings. Where there are discrepancies, serious remediation steps must be taken. This will foster a step toward better governance and create the conditions for real accountability to take root.

In closing, it is important to develop and continue to strengthen mining codes such as the EITI to create standards that promote transparency which leads to effective accountability mechanisms. The Glencore case has shown that corrupt corporate culture and misconduct has been tolerable for many years because it does not apparently break any laws. Independent monitoring agencies supporting the work of regulatory bodies will be crucial for keeping corporates like Glencore in check. For good governance to prevail, incentives for compliance need to be developed alongside credible deterrents for non-compliance. More importantly, willingness from corporate leadership teams and governments respectively to curb bribery and corruption will be critical for attaining better governance in the industry. It has to become increasingly evident to all players that taking social responsibility and good governance seriously – by at least avoiding behaviours that entrench and normalise corruption – is ultimately good for business.

This article first appeared in Mail & Guardian, here.

[activecampaign form=1]

Busisipho Siyobi is the Programme Head of the Natural Resource Governance Programme at GGA. Before joining GGA, she headed up the Corporate Intelligence Monitor desk at S-RM Intelligence and Risk Consulting. Busisipho holds an MPhil in Public Policy and Administration from the University of Cape Town with a research focus on CSR within the South African mining industry. During her Master's, she worked as a research scholar at the South African Institute of International Affairs.