Skaters gathering to celebrate Youth Day in Soweto, Johannesburg, on June 16, 2021. Photo: Guillem Sartorio/AFP

There are many contestations over the definition and constitution of ‘youth’. In South Africa, according to the recent National Youth Policy, those within the age group of 15-34 make up more than a third (34.7%) of the population. At the age of 16, one can register to be a voter, then at the age of 18 one is eligible to vote. South Africa has witnessed a decline in voter turnout across age groups in every election after the landmark 1994 national elections, but more so amongst the youth.

The 2 November 2021 Local Government Elections (LGE’s) provided a good opportunity to inspect the role of this cohort in the state of politics and democracy. Youth participation in how they want to be governed and official representation in institutions that are tasked with decision-making to that effect is also essential for the existence and wellbeing of democratic political culture, and the effective governance of their spaces.

South Africa is contending with a multitude of economic, social and political challenges. Burning challenges include a stagnant and declining economy, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and widespread public sector corruption. The challenges have significantly fuelled unemployment, deep-seated poverty, widened inequality and exacerbated competition for already scarce socioeconomic resources and opportunities. While not all exhaustive and uniformed and confined to a single problem, these issues impact the country’s youth at an individual and collective level; not only are they barriers to participation, but they also fuel disillusionment with the governing architecture.

Is apathy a defining characteristic?

Much has been written and said about people in this age cohort. A significant issue is a reluctance to participate in formal political processes, a key characteristic being a lower-than-expected ballot turnout. Political apathy amongst the youth is not unique to South Africa. Globally, in established democracies and developing ones, younger people tend to participate less in conventional politics and frown upon formal voting processes. An exceptional example that goes against this norm much closer to home is the 2021 Zambian national election. Zambia, a country where more than 60% of the adult population is between 18 and 34 years old, experienced its highest voter turnout in 15 years at 70.61%, with the youth vote playing a decisive role in the outcome.

What does the data say?

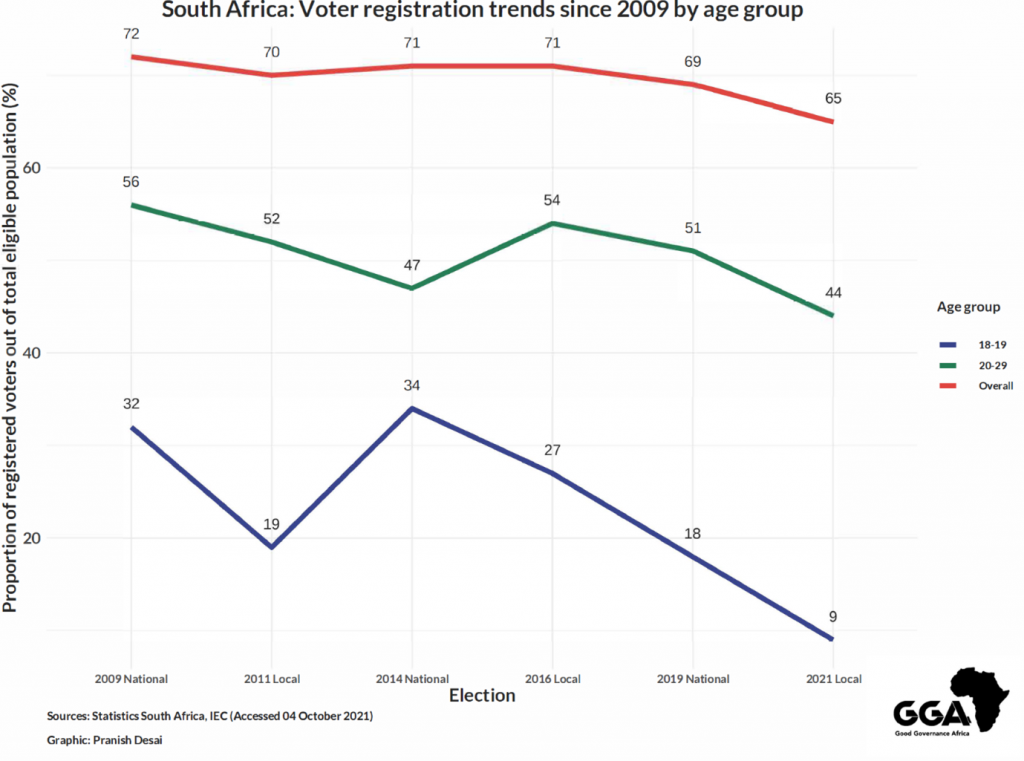

The voters’ roll for the 2021 LGE’s suggests that the number of registered voters across all age groups as taken as a proportion of the total number of eligible voters has declined since the 2016 LGE’s. This decline, visualised in the graph below, suggests a decrease in citizens’ interest in participating in electoral politics. However, even more concerning is the rapid decline in the registration rates for South Africans in the 18-19 and 20-29 age groups, especially since the 2014 National Election. That the decline has been evident for so long, demonstrates that this low registration rate cannot solely be attributed to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

In the 2 November 2021 elections, nearly 1.8 million eligible 18–19-year-olds decided against registering to vote. Registration rates among the 20-29 age group also declined since the 2016 LGE’s. This decline is troubling because it suggests that compared to before, a larger number of the former 18-19-year-olds who are unregistered also decided to not register in their 20s. Even worse, it implies that this group is falling out of the electoral process altogether, thereby increasing the overall population of non-voters in South Africa.

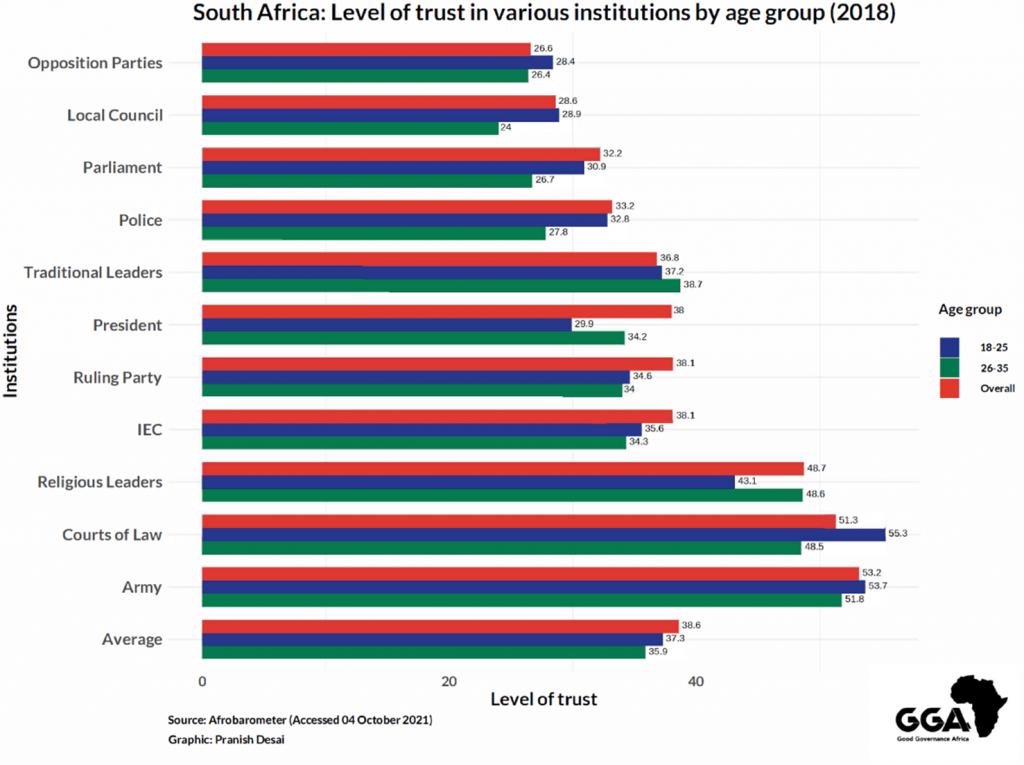

As with any social phenomenon, it is difficult to attribute this decline in voter registration – particularly among younger South Africans – to any single cause. Nevertheless, one likely explanation for these declines is the lower levels of trust which younger South Africans have in various political and social institutions. According to data collected in 2018 by the pan-African survey, Afrobarometer, while political trust in South Africa is generally low, surveyed South Africans in the age groups of 18-25 and 26-35 are less likely to trust surveyed institutions in South Africa.

One data point which does not augur well for the 2021 LGE’s is the indicated level of trust in local councils, which as the graph below shows, stands as the second least trusted institution overall among 18-25-year-olds and as the least trusted institution for the 26-35 age group. This low level of trust indicates that while the government needs to make a conscious effort to increase social and political trust across the board, one area that requires particular attention is the level of trust South Africans have in local government institutions. Unless swiftly addressed, increasing cynicism in local government, particularly amongst younger people, will continue to result in less participation in elections for this sphere of government.

Youth in the municipal space – a site of opportunity?

Municipalities are at the coalface of service delivery. Considering the proximity of this sphere, it is the site of a direct interface with the government for most people. It is where they live, work and play. As a sphere of governance, the local municipality provides both technical and administrative services for populations. Municipal provisions range from water, sanitation, electricity, collection of refuse and maintenance of road infrastructure. Other deliverables include primary health to public libraries and the administration of by-laws, municipal permits, and fines. The multitude of frustrations around service delivery, ranging from incapacitated municipal bureaucracy, extensive red tape, the poor state of roads, water and electricity, and evident acts of corruption, make survival difficult, and leads to a trust deficit among young people.

Historically, it has been a challenge to encourage the presence and cultivation of younger political leaders in South Africa. This problem is especially clear at the national level, where the political space still lags in accommodating youth. Parties have often put out conflicting messages about youth leadership. This is seen in how the Democratic Alliance (DA) has historically treated its young and black leaders; the purging of Lindiwe Mazibuko, Mmusi Maimane and treatment of Mbali Ntuli are such examples. Another example is within the African National Congress (ANC); after the last national election in May 2019, only one cabinet minister, Ronald Lamola, was classified as falling in the youth cohort.

The emergence of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) as a political force is often cited as an example of the increased presence of young people in South African politics for both representation and voting. Yet, voter registration rates among young people have continued to decline even after the party’s founding in 2013. Ahead of the LGE’s, political parties are beginning to recognise this lack of representation. One example of this is the ANC’s promise to ensure that 25%, or 1 in 4 candidates, for the upcoming LGE’s are young people. However, political parties need to ensure that they fulfil these pledges or risk worsening the already worrying trends observed among young people in their voter registration rates and their levels of institutional trust.

Yet not all South Africa’s young people can be politicians, councillors and mayors. Municipalities need professional expertise to run effectively, both technical skills, from water scientists to engineers and town planners to skilled administrators in the form of financial managers and support services. The local government space has been politicised extensively, and as a result, across the entire municipal hierarchy, appointments to positions are often not based on merit but party lines.

Programmes such as the Expanded Public Works in municipalities, to provide opportunities for skills and income for unemployed and underemployed people, are often used as a way of rewarding party loyalists. The appointment of unqualified cadres to senior-level positions is also common, eg., the Marietta Aucamp scandal in the Tshwane Metro. Thus their lack of political connections explains, to some extent, why skilled and educated youth are excluded from jobs. This goes against the impetus of public service professionalisation and leads to frustration, alienation, and ineffective governance outcomes.

What is the way forward?

The need to interrogate the societal, economic, and political factors that continue to undermine good governance efforts and reinforce existing patterns of exclusion that fuel disengagement is apparent. It is a given that young people will, in future, bear the brunt of current decision-making. As such, engaging and capacitating youth as critical stakeholders is of utmost importance. Youth inclusivity in decision-making on governance is not a favour that must be commended. It is a necessity that must be prioritised if the country is to make meaningful strides towards sustainable development at all levels.

Importantly, the local state must provide opportunities for access growth and governance by empowering the young to bring forward-thinking and innovation to current problems, this can be done by incentivising adequate skills. Furthermore, voting must be encouraged as a form of political expression; this can be achieved by strengthening agency through civic education drives. Participation in voting will encourage solid choices and effective responses to concerns such as corruption. Managing these key considerations will be crucial for those who seek to attain the youth vote as the election approaches.

This article first appeared in the Mail & Guardian.