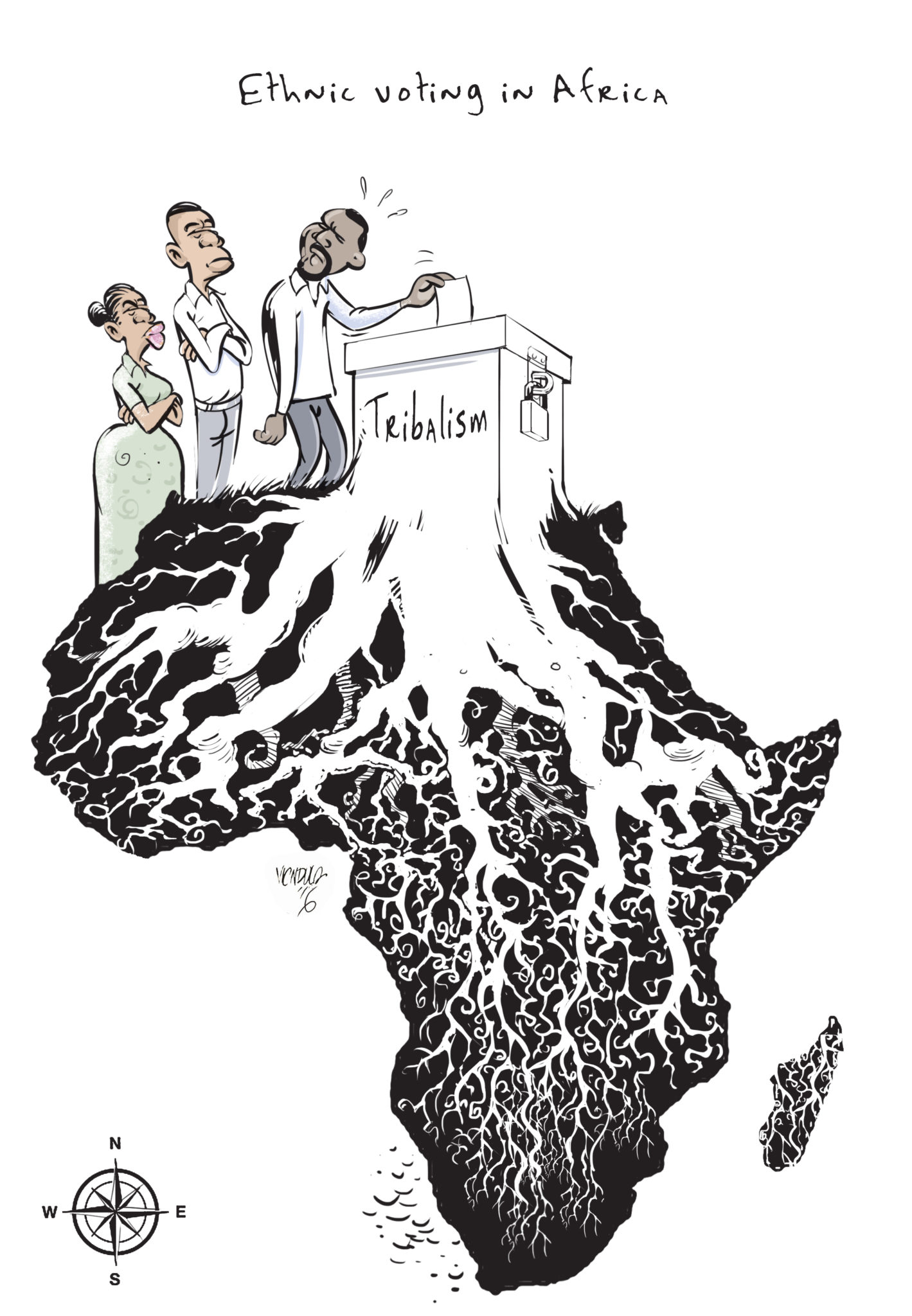

Kenya: deadly politics

Ethnic factionalism results in skewed allocation of resources and opportunities towards majority tribespeople

Last year three Kenyan universities closed indefinitely after a poisonous division emerged between two groups of students contesting the outcome of their respective leaders’ elections. The closures revealed an underlying division at Kenyan institutions of higher learning where students mobilise along tribal lines, especially during elections. At all three universities—Chuka, Maasai Mara and Moi— one group was mainly made up of Kikuyus and Kalenjins, while the other included Luhyas, Kisiis and Luos. Together, Kikuyus and Kalenjins make up 11.6 million of the population, and Luhyas, Kisiis and Luos 11.2 million, according to the 2009 census. “These happenings disproved the fact that education can refine an individual and an institution,” said Wanyonyi Buteyo, a political analyst based in Bungoma, western Kenya.

Masaai, Kenya © Creative Commons

Despite their relative size as a group, Luhyas, Kisiis and Luos feel left out of the country’s leadership. Kikuyus and Kalenjins have dominated politics and the civil service since independence. Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, was a Kikuyu. His successor, Daniel arap Moi, was a Kalenjin. In 2002, Mwai Kibaki, a Kikuyu, took over from Moi. In 2013, Uhuru Kenyatta, son of Jomo Kenyatta, was elected Kenya’s fourth president. William Ruto, a Kalenjin, and current deputy president, is likely to succeed Kenyatta as president in 2022. The two control a formidable political and tribal alliance known as Jubilee. The frosty relations between different tribes in Kenya date back to 1963, says Buteyo. Before the arrival of the British colonialists, he asserts, little or no animosity existed between communities. Intermarriages, which today are seen as taboo, were common then. The British settlers brought the divide-and-rule principle, magnifying differences amongst the various tribes and instigating conflicts among them. This encouraged negative tribal stereotypes. The Kikuyu, for instance, were led to believe that Luos were indolent, uncircumcised and unreliable, while the Luhya were encouraged to view the Kikuyu as schemers and thieves. The sorry situation underlay the formation of tribal political parties after independence. The Kenya African National Union (KANU) was dominated by Luos and Kikuyus, while the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) was controlled by people from the other ethnic groups, who feared that Luos and Kikuyus wanted to “finish them” politically. KADU insisted on majimbo, a federal system of governance, arguing that it would shield the smaller tribes from exploitation by the Kikuyu and Luo. However, majimbo was discarded when KANU’s unitary system carried the day. When Jomo Kenyatta became president his regime unapologetically favoured Kikuyus. The ethnic favouritism manifested itself in skewed government spending and privileged access to government and parastatal jobs. Though the former vice-president, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga was a Luo, members of his group were looked down upon, and when they complained, subjected to intimidation and assassinations. When Tom Mboya, a senior Luo politician and minister, was assassinated in 1969, his death was blamed on Kikuyus. The enmity between Luos and Kikuyus has continued since then. Ethnic loyalty has seen a lack of accountability, underdevelopment and poor governance, fostering the rise in corruption in Kenya, says Isaiah Cherutich, a lecturer at the United States International University-Africa. Kenya is among the most corrupt countries in the world, according to Transparency International. Recent scandals include a currency printing scam, procurement and staffing irregularities at the National Youth Service, and an electoral system scandal (known as the Chickengate Scandal), among many others. No one has been held to account in any of these matters. “It is not because the country’s laws are weak; it is the tribe factor that chiefly determines if one should be declared innocent or guilty before a court of law in Kenya. A Kikuyu or a Kalenjin thief is as good as an angel today because the two tribes control more than 70 percent of key positions in the public service,” says Emmanuel Manyasa of Kenyatta University. “A Kikuyu man who has stolen $10,000 is [more] likely not to face the laws of the land [than] a Sabaot [man] who has stolen an egg.” The media have also been caught in the tribal mess: some outlets deliberately fail to investigate people in power because they are perceived as the kinsfolk of their owners and managers. The church, traditionally seen as a neutral arbiter, has not been spared. The Presbyterian Church of East Africa, for instance, openly endorsed President Kibaki’s candidature in 2007 and urged all its followers to vote for him. Most of the church’s senior leaders are Kikuyu. Luke Mulunda, managing editor of Kenyan news outlet businesstoday. co.ke, says tribalism was the main contributor to the killing of more than 1,200 people in 2008 following a rigged poll. The 2007 election saw Raila Odinga—a Luo and son of Oginga Odinga— amalgamate 41 tribes against the Kikuyu-led government of Kibaki, and was not based on issues, ideologies or principles. Rather, it was an avenue for voting out the Kikuyus. Violence broke out when it became clear that the election had been rigged. People from President Kibaki’s tribe were hunted down, attacked, maimed and evicted from their homes all over the country. “Tribal leadership saw [an] opposition chief outrightly denied [the] presidential seat. There is no way powerful Kikuyu mafia and businessmen would have allowed a Luo [Odinga] to be the head of state,” argues Mulunda. Tribalism is being “perfected each new day in Kenya”, says Manyasa. “Under the current regime, we have witnessed the worst form of negative ethnicity in this country’s history. Those people and regions perceived to be from tribes that are anti-government have been punished, with minimal national resources allocated to them.” The neglected regions include opposition strongholds such as Nyanza, Coast, and eastern and some parts of western Kenya. Ethnic background still determines access to lucrative jobs in government and parastatals such as the Communications Authority of Kenya, Central Bank of Kenya, Kenya Revenue Authority and the Ministry of Finance. “We are living in a country where we have thousands of extremely rich people, and millions of paupers. Tribalism is all to blame for this huge gap,” observes Mulunda. The Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission—established to heal Kenya of the tribal divisions that emerged in ethnic conflicts in 1992, 1997, 2007 and 2013—has so far achieved little. “When the government says it has created more than a million jobs in a year I wonder where that is. Only Kikuyus or Kalenjins appreciate the said numbers,” says Maurice Ochieng, 23, an engineering graduate and jobseeker. To rid Kenya of ethnic tension, Okoiti Omtata, an activist, says leaders should learn from Tanzania and Rwanda. In Tanzania it’s almost illegal, and certainly frowned upon, to speak in one’s ethnic language in a public context; in that respect, Swahili has unified the country. “Rwanda is a perfect example to Kenya of how perilous this stupid mindset on tribalism can be,” says Omtata, referring to the 1994 genocide. He adds that Rwanda’s approach to de-ethnicising politics since 1994 can give Kenya “proper lessons” on “healing and bonding as a unit”. Kenya should go to the root causes of tribalism, and address each exhaustively, he argues. A major factor is the skewed allocation and distribution of national resources, particularly land, associated with ethnicity-based politics. “A clear formula of power and resource sharing should be instituted through constitutional arrangements. This has already started with the coming into play of devolution,” he says. Wanyonyi adds that the country needs appropriate legislation to curb discriminatory practices in the provision of public services. “If this is followed we will have a stable and unified nation,” Mulunda says, adding: “For now, the country is in deep tribal shit.

Mark Kapchanga is a senior economics writer for the Standard newspaper

in Kenya and a columnist for the Global Times, an English-language newspaper

in China. He is pursuing a PhD in investigative business journalism at the

University of Nairobi.