In February of this year, following an insurgency mounted from a nation called Wakanda, a young king forcibly took over Africa. At the time, no one seemed to mind: backed up by a dazzlingly capable all-female Republican Guard, riding wave after wave of Kendrick Lamar’s Pulitzer-worthy hip hop, T’Challa – or, as he is more widely known, Black Panther – was both soulful and handsome, intelligent and urbane, tough and tender.

As is usually the case in these matters, his reign was controversial from the start. Following his murdered father to the throne, whom exactly did T’Challa represent? Was he the avatar of a new form of black consciousness that saw itself not just equal to, but better than, the boilerplate whiteness that has defined the notion of “civilisation” for so long?

Was he the vanguard of a new, youthful Africa hoping to redefine the notion of home as something other than the pit of misery and despair depicted by Western media? Or was he simply the product of the Marvel cinematic universe – a $17 billion Hollywood behemoth that dominates the cultural discourse with its engorged biceps and fancy leotards. That is, was he a means of selling fast-food burgers to mid-western families with no interest in black liberation?

T’Challa himself didn’t seem to know the answer to these questions, locked as he was in a blockbuster that quickly broke global box office records. Until that point, the consensus in Hollywood was that black movies didn’t sell abroad. This one has sold pretty well: to date, it’s grossed over $1.3 billion worldwide. The film’s director, Ryan Coogler, is black; the cinematographer, Rachel Morrison, doesn’t bear a Y chromosome – almost unheard of in big-budget filmmaking.

Indeed, outside of the white dudes who signed the cheques, and in the context of America First, Me Too, Black Lives Matter, All Lives Matter, and the mainstreaming of the Ku Klux Klan, Black Panther suggested what the world would look like if our entertainment was created by those who have long been considered “outsiders”. The film hit with the force of a vibranium-powered guided missile, and it was difficult not to consider its reception transformative for the American entertainment industry.

Largely forgotten in all this was what actual Africans thought about their new king. Weaponised rhinos notwithstanding, the continent seemed like more of an afterthought – or a catch-all for an encompassing, global blackness. Which begs a slew of questions. How widely was the film viewed in Africa? Who watched it? What of the African diaspora, where dozens of the continent’s brightest young people enliven Western culture as novelists, musicians, filmmakers and academics? And, perhaps most importantly, what does “African” even mean in 2018, as the continent gets younger, busier, more urbanised, more wired?

In the golden age of digital piracy, it’s impossible to know how many Africans have watched Black Panther since its release – its box office figures, while record-setting, don’t tell us much about its actual impact. Which makes it difficult to get a sense of how the idea of Wakanda – a stand alone, proudly independent technotopia – might inform new concepts of what Africa can mean, can produce, can become.

As it happens, the film dropped during the reign of Trump, a political phenomenon that represents the near total capture of the US by a narrow oligarchy (the parallels with Mobuto Sese Seko’s Zaire are glaring, if not flattering). But while America Africanises, Africa atomises. No African nation presents a definitive case study for what “Africa” is supposed to look like, if there ever was.

Marvel Studios’ BLACK PANTHER (L to R) Okoye (Danai Gurira), Nakia (Lupita Nyong’o) and Ayo (Florence Kasumba). ©Marvel Studios 2018

So why not Wakanda?

It would be nice, but it’s difficult to see how this concept-as-place could gain any purchase at so strange a point in liberated Africa’s historical trajectory. The continent’s most entrenched and lauded strongman is busy turning his capital city, Kigali, into a model of Wakandan innovation. Or is it the other way around? Angola lost its own strongman last year; within a matter of months João Lourenço had wiped away the Eduardo Dos Santos regime’s more corrupt cronies, including ranking members of the former president’s clan. Kenya found itself engaged in an absurd election campaign, during which the reigning members of the oligarchy – Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga – locked horns, the latter refusing to give way after the results favoured the incumbent.

In other developments, Ian Khama, dynastic leader of Botswana, stepped away with barely a nudge; his successor, Mokgweetsi Masisi, is a technocrat and long-serving cabinet minister. In Ethiopia, after the Tigrayan prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, voluntarily left office, he was succeeded by Abiy Ahmed, an Oromo, who is tasked with ending centuries of enmity between the country’s ethnic constituencies.

And in South Africa, after what seemed like an endless and unwinnable battle, Jacob Zuma’s faction was defeated at the African National Congress’s electoral conference; a short time later, Cyril Ramaphosa—a vastly wealthy, vastly cosmopolitan centrist—became president of the country.

These are just a few of the political transitions that have occurred on our continent during the past year (George Weah becoming president of Liberia? Robert Mugabe’s fall in Zimbabwe, anyone?). For the most part, stodgy old-school elites have been replaced with Davos-steeped technocrats. New blood has without question resulted in new energy: South Africa, Angola, Ethiopia and Zimbabwe are undergoing serious makeovers. But it cannot be said that all of these men – and they are all men – are particularly young. I put their average age at around 60. Nor can it be said that they are ideologically diverse, or economically imaginative.

And here’s where the parallels with Wakanda come perversely full circle. The central conflict in the film is between T’Challa and his long-lost cousin, who calls himself Erik Killmonger. The latter grew up in inner-city Oklahoma, his life defined by American racism. Without giving too much away, Killmonger returns to Wakanda with the intention of seizing the throne, and using the kingdom’s killer tech to prosecute a war against the empires of the West, with the aim of vanquishing them in the interests of true liberation.

A poster for the film Black Panther © Marvel Studios 2018

It’s been noted by many commentators that while Killmonger is the film’s ostensible villain, there’s a case to be made that he’s the actual hero. A genuine revolutionary, Killmonger wants global racial freedom, and he’s willing to pay the price in blood. T’Challa refuses to be party to a revolution, however bloody, and regardless of the outcome.

For the most part, Africa’s new leaders are all T’Challas – they’re about as revolutionary as a dishrag, and acceptable to bland Western mainstream audiences. These are men who have consumed their fair share of World Economic Forum crustless sandwiches, and they are here to institute government by best practices. Does this mean they can help ameliorate their countries’ many problems? Can they institute fairness and equality and leadership for all?

Perhaps. But Ramaphosa, Ahmed, Masisi, Mnangagwa weren’t voted into power by a popular majority – they were installed in their positions of leadership either by their parties or their parliaments. Meanwhile, the Angolan and Kenyan elections were seriously contested.

This means that, much like T’Challa, they aren’t properly democrats, but a mix of old school and new school, political creatures that share a surprising number of attributes for a continent as large as this one. “Wakanda Forever!” goes the battle cry.

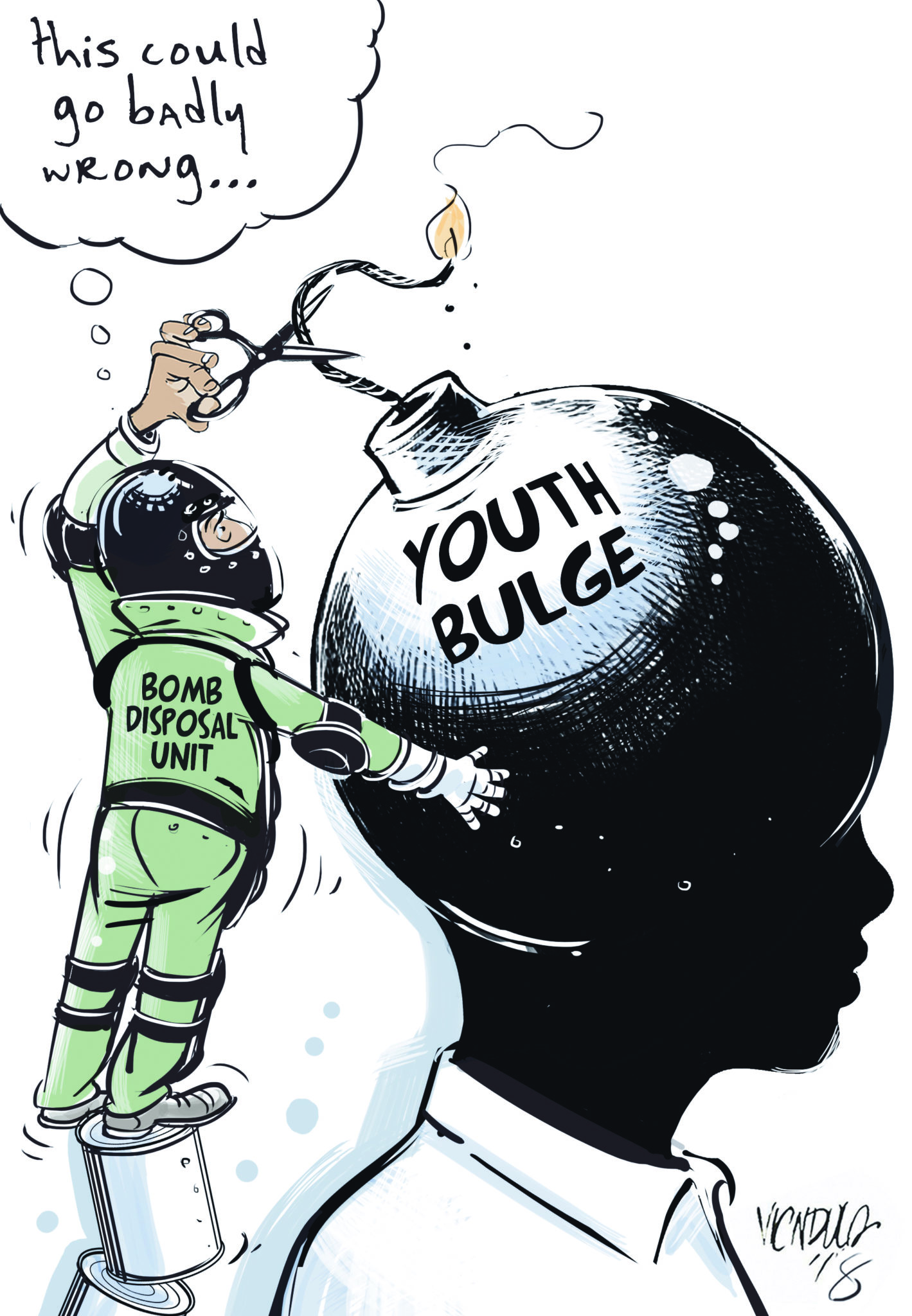

But this latest wave of change will likely not be as durable as that unless it receives some endorsement from the people. Which means, these days, and more and more: Africa’s young people. And increasingly, too, they aren’t likely to be the cheerleaders of an older generation.

Black Panther, produced by Marvel Studios, directed by Ryan Coogler and starring Chadwick Boseman, Michale B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong’o and Martin Freeman.

By mid-June this year, Black Panther had taken over R107 million, with more than 1.4m attendances, at the South African cinema box office. South Africa joined East and West Africa in claiming the film as the highest-grossing film of all time in these regions.

Richard Poplak is an award-winning freelance journalist and author, who has worked extensively in Africa and the Middle East. His book “The Sheikh’s Batmobile: In Pursuit of American Pop Culture in the Muslim World” won positive reviews in The Economist and elsewhere. He is currently writing a book and starring in a documentary series on Africa rising, called Continental Shift.