African woman from Maasai tribe collecting water to the tank, Kenya, Africa. When she finish filling the tank, she will carry water on her back to the village. African women and also children often walk long distances through the savanna to bring back containers of water. Some tourist camps cooperating with nearby villages and allow local people to use their water. Maasai tribe inhabiting southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, and they are related to the Samburu.

Food and water insecurity have saddled Africa with a risk tantamount to a pandemic, but the COVID-19 shock has made the threat even more and immediate. Water scarcities and poor sanitation services, food insecurities and starvation plagued Africa prior to COVID-19, partly caused by meagre water investments and a stunted green revolution. Climate change, exacerbating food insecurity and water scarcity, now pose an enormous threat to regions across the continent, including southern Africa, the Sahel and the Horn of Africa.

Poverty is the main inhibitor of access to food and water. According to the World Bank, while poverty decreased from 54% in 1990 to 41% in 2015, Development Aid, an organisation that provides comprehensive information services for the international development sector, has revealed that in 2021 there are 490 million people in Africa living in extreme poverty, an increase of nine million from 481 million in 2019. African countries still have the highest poverty rates in the world, due to a growing population. A massive health burden is inevitable, demand for water and sanitation outstripping supply due to urbanisation.

According to World Vision, as of 2019, 234 million people in sub-Saharan Africa were acutely undernourished, while 250 million people, 20% of the population in Africa, were experiencing hunger. One in three people on the continent faces water scarcity, and approximately 400 million people in sub-Saharan Africa lack access to basic drinking water. “Africa’s water and sanitation sector is historically under-funded, and this challenge persists to this day,” says

Alex Simalabwi, the executive secretary of the Global Water Partnership Africa Coordination Unit. “Actually, the dual challenge of the pandemic and climate change crisis have only served to accentuate the massive gap that exists between the level of investment we have now, and the level of investment we need to see to achieve the 2025 Africa Water Vision of water security for all.”

The African Development Bank estimates that $64 billion in water infrastructure investment is required annually, but the actual figure invested is between $10-$19 billion per year. Simalabwi also believes that the political leadership needed for ongoing and new water investments is inadequate, given Africa’s many competing developmental priorities; water-related interventions in health, energy and food security are not coordinated, even though they are inextricably linked. Therefore, he says, investments in various development priorities exist in silos, and this undermines the opportunity to mobilise the funding needed for the magnitude of the water projects that Africa requires.

The majority of Africa’s water is transboundary – it crosses country borders. New water projects need cooperation between multiple countries and the legal, regulatory, and institutional frameworks to assist the projects to move forward their life cycles. These processes are insufficiently developed. Thus, the preparation of projects and implementation of bankable transboundary water projects is slow.

A case in point is the situation on the Nile river. In 2010, six upstream countries (Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania), signed a Cooperative Framework Agreement, seeking a greater share of the river’s water, which Egypt and Sudan rejected. With time, Ethiopia began planning for dams on the Blue Nile, which led in 2015 to the $4.2 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) project.

The macro-economic strategies to address the water situation in Africa will be sustainable and maintainable through the minimisation of water usage – reduce, re-use and recycle – as well as the protection of water resources and the avoidance of pollution.

As indicated by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Africa’s ambition of reaching zero hunger by 2030 seems highly unrealistic. To reduce hunger, a prudential reformation approach to agriculture in Africa needs to be adopted. Agriculture makes up a a large portion of the economies of all African countries; Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) has found that agriculture employs some 60% of Africa’s labour force, while the World Bank says it accounts for between 30–40% of the continent’s GDP.

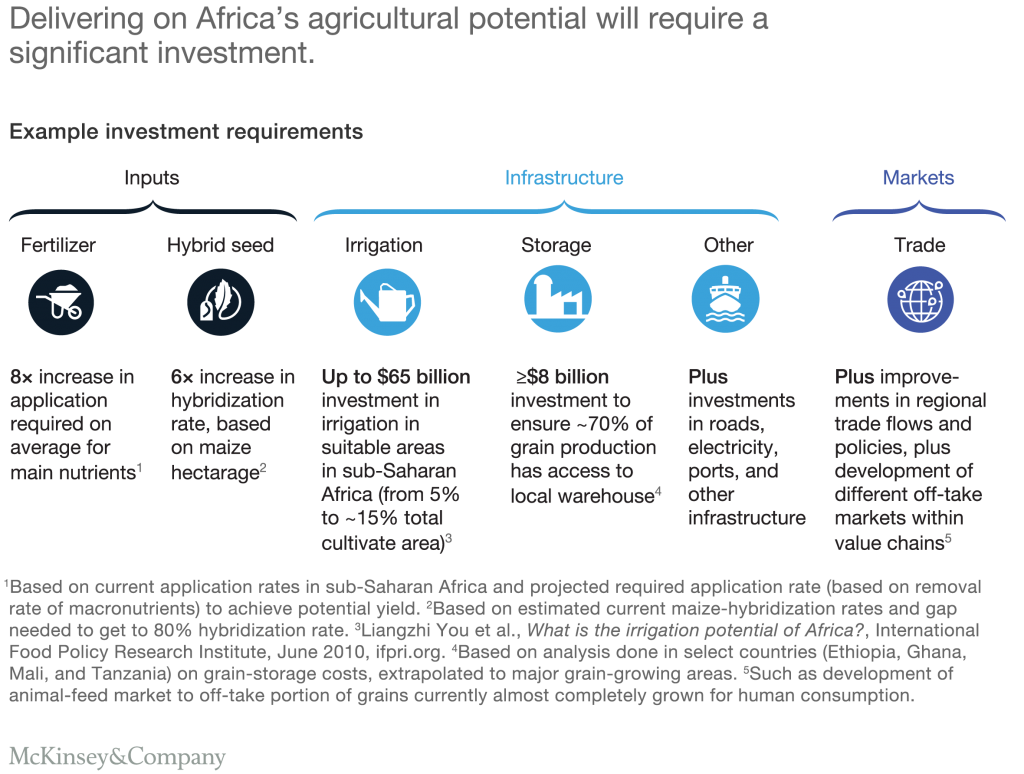

“Farmers need to be at the forefront of gaining access to inputs such as land, seeds, fertilisers, mechanisation, and water; and adopting agronomic practices for soil management to cope with climate change, etc,” says Ruhiza Jean Boroto, a senior land and water officer at the FAO. “Capacity building, institutional support, and access to finance are key.”

Boroto says exporting is paramount, and transforming products such as coffee, tea, and cocoa needs perfect combinations of infrastructure, energy, roads, and IT, to maximise “added value” before export, so that Africa gets the most of the benefit from its food systems. Leveraging the

African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) will galvanise these efforts and reduce reliance on imports. This way, apples and potatoes from South Africa can reach Nigeria, and yam or rice from West Africa can reach southern Africa. Strategic food reserves are important at household, community and national levels, to minimise the risk of food insecurity caused by scarcity during a pandemic.

Dietary mechanisms and education are essential tools, too; promoting food safety measures at all levels as part of broad hygienic standards to manage opportunistic pandemics is crucial. Overall, social protection measures need to be in place for the most vulnerable in society. To achieve all of the above, the need for sound political environments and stalwart leadership cannot be overemphasised.

Technological advancements (4IR) and scaling up ICT programmes will help Africa meet a steep demand for food and water. Technology has been instrumental in mitigation in the past seven decades. Linkages between the food and water sectors with other fundamental entities such as, and especially, energy, must be realised. “Africa faces a food security paradox and a drinkable water crisis,” says Paul Noumba, the regional director of infrastructure for the Middle East and North Africa at the World Bank. “A food security paradox, because the continent has not done its green revolution, and still relies on food imports, although it has abundant arable land and the bulk of its population is rural.”

Noumba says four things need to happen for a successful green revolution on the continent. First, governments need to ensure peasants have access to water through small-scale irrigation, and also take advantage of declining solar energy costs to scale up output. Secondly, farmers must have access to certified seeds and other critical inputs on affordable terms. Farmers must also be connected to markets through upgraded road infrastructure. Fourth, countries must facilitate food transformation through agro processors, improved storage facilities and output aggregation.

With access to finance not necessarily prioritised, if these prerequisites were met through smart government interventions, private investors would invest in food production. Africa’s water sector challenges reflect institutional failures. Water is, in most cases, locally tapped and very expensive to transport. Water utilities should be as close as possible to the demand they serve, recognising that access to water is a human right. The economic and health costs related to poor quality water are enormous, so governance structures should empower citizens to drive efficiency and expansion programmes.

The COVID-19 pandemic reminds us of the imperative of effective governments that deliver results. To attain Africa’s development goals, the continent’s economies ought to prioritise research and development partnerships, the teaching of science, technology engineering and mathematics (STEM), and digitisation in the water, food, energy and health sectors. Besides covering food, water, and risk, in a business-as-usual set up, the listed components will boost resilient infrastructure, resuscitate employment rates and equity, and close the skills gap.

Derick Mazarura

Derick Mazarura is an energy, agriculture and infrastructure fellow, as well as a self-taught writer, screenwriter, film and TV producer and director. He is interested in the change process in Africa, and giving voice to the voiceless, marginalised and the disadvantaged.